Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE) was a religious reformer, Puritan preacher, midwife, and alleged prophetess whose beliefs and influence brought her into conflict with the magistrates of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, especially its governor John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) in 1636-1638 CE. She was the central voice of the so-called Antinomian Controversy which divided the colony and, to the magistrates, threatened its mission and continued existence. Hutchinson claimed that the ministers of the colony were preaching a false doctrine of salvation based on works while ignoring the truth that salvation was granted by God's grace alone.

Winthrop and the magistrates countered her, claiming that God's grace in one's life is made evident by one's works, and objected to her influence over others in the colony on three points:

- She was a woman and, as such, had no authority to preach, especially to men.

- She undermined the religious authorities by claiming that works had no bearing on salvation.

- She claimed she had a spiritual gift that allowed her to tell who was among God's elect and who was not, claiming knowledge only God could have.

Hutchinson ably defended herself in court, citing scripture to back up her defense, but her judges refused to be taught doctrine by a woman, and she was banished from the colony in March 1638 CE. Hutchinson left Massachusetts Bay Colony and settled the region which would become Portsmouth, Rhode Island after her trial. In 1641 CE, her new settlement received word that Massachusetts Bay Colony was expanding and might absorb the surrounding settlements of Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. She left the region with seven of her children, a son-in-law, and servants to relocate to New Netherlands (modern-day New York) establishing a homestead in what is now the Bronx in 1642 CE.

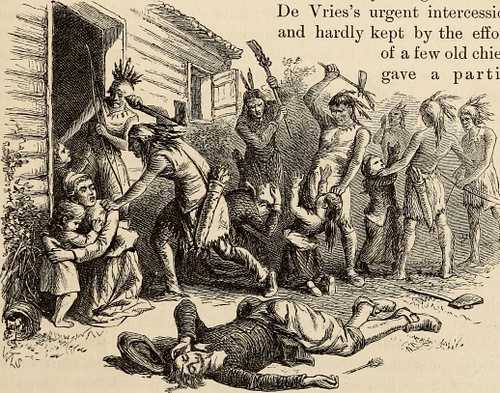

She and all of her children save one were killed in an attack by the Siwanoy Native American tribe in 1643 CE during the conflict known as Kieft's War (1643-1645 CE). Her daughter, Susanna (later Susanna Cole, l. 1633-1713 CE), was taken by the Siwanoy and married to their chief Wampage I (d. c. 1680 CE) with whom she is said to have had a son.

Winthrop, and the other magistrates who had condemned her, interpreted her death and the capture of her daughter as a justification of their verdict and God's punishment of her sins. Others, since her death, have disagreed and honor her as a visionary, reformer, and advocate for true religious freedom against the authority of the Puritans of Massachusetts. This view has gained greater support in the modern era, and she is regarded as a 'founding mother' and one of the most impressive figures from the period of Colonial America.

Early Life & Influences

Anne Hutchinson was born in Alford (pronounced Olford), Lincolnshire, England in 1591 CE, daughter of the Anglican preacher Francis Marbury and his wife Bridget. Anne was the third daughter of the 15 children the couple would have and seems to have been a favorite of her father. Francis Marbury was a Puritan sympathizer, who openly criticized the Anglican Church he served for and its policies, especially that of ordaining uneducated and immoral men as priests. He was at first censured and then imprisoned after an ecclesiastical trial.

The head of the Anglican Church was the monarch of England and so criticism of church policy or practice was tantamount to treason. Once Marbury was released from prison, he was given house arrest, and during this time, he composed a transcript of his trial from memory, which he would later read to Anne and her siblings along with the Bible and Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Marbury's version of the trial cast him as the brave Christian champion of truth fighting against the ignorant and stubborn establishment of the Church; an image which seems to have impressed itself upon Anne as she would remain outspoken, confident, and unrepentant of her interpretation of the Bible for the rest of her life.

When she was 15 years old, the family moved from Alford to London, and they were present in the city when Guy Fawkes and the other Catholic conspirators attempted to blow up Parliament in November 1605 CE. Although many, if not most, around her interpreted this act as proof of the 'evil' of Catholicism, her father had impressed upon her the conviction that there was little difference between Anglicanism and Catholicism.

Her father encouraged this conviction through his sermons and instilled in her the Puritan view that the Anglican Church was in need of reform and a true Christian should not be afraid to speak out against corruption or injustice no matter the consequences. Francis Marbury died suddenly in 1611 CE, and Anne lost her main confidante and mentor. The next year, she married a young merchant of means, William Hutchinson (l. 1586-1641 CE), who was from Alford but then working in London. After their marriage, they moved back to Alford.

John Cotton & Migration

In Alford, the couple heard of a young Puritan preacher, John Cotton (l. 1585-1652 CE), some 20 miles away in Boston who had acquired a reputation for his zeal and eloquence, and they made the journey to hear him. Cotton was a strict Puritan who recognized the Church needed major reform but, unlike those of the separatist movement, refused to leave it, preferring to change it from within. Anne and William became devoted to Cotton and were especially influenced by his insistence on God's grace as the sole factor in one's salvation; there was nothing one could do to win God's favor or merit eternal life because everyone was a sinner, and only by God's own election would a soul be rewarded with eternal life.

Those whom God had chosen were known as the elect, and others would be eternally damned. No one knew who was headed for which eternal destination, however, and so Puritan theology held that one should act as though one were saved and praise God for his goodness and mercy even if, in the end, one's soul was destined for hell. This belief was not Cotton's alone, it was the general understanding of Puritan belief, but Cotton placed special emphasis on grace-not-works while most Puritans believed that doing good deeds, attending church, reading the Bible, and being an upstanding member of the community established a Christian as one of the elect; one's outward behavior and financial success reflected one's inward salvation.

Cotton was a charismatic and diplomatic clergyman who was able to maintain his position at Saint Botolph's Anglican Church for 20 years, even though he frequently preached reform or theology which contradicted the Church's official stand. Anne and William regularly made the trip with their children to hear Cotton preach, and he became her spiritual mentor. At about this same time (c. 1629 CE), Anne's sister Mary was married to the Puritan preacher John Wheelwright (l. c. 1592-1679 CE) who was vicar of the church at Bilsby, closer to Alford, and Wheelwright encouraged Anne to hold meetings in her home known as conventicles during which women, primarily, would meet to discuss the latest sermon, the Bible, and their personal spiritual concerns.

Cotton's successful run at Saint Botolph's ended in 1633 CE when Archbishop William Laud (l. 1573-1645 CE) was purging churches of Puritan pastors. Cotton hid from authorities until he could book passage on a ship to New England. The authorities of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who had heard of his zeal and ability to win souls for Christ, had been wooing him for years and so he left Boston, England, for Boston in the Massachusetts colony. In 1634 CE, Anne Hutchinson and her family followed him.

Meetings & Popularity

The Massachusetts Bay Colony had been united under the leadership of John Winthrop who emphasized the importance of a cohesive vision and conformity from all its citizens. Winthrop's famous sermon A Model of Christian Charity made clear that this colony was to be that model for the whole world and only those willing to act in accord with this vision would be welcomed. When Cotton arrived, he got along well with Winthrop and the others, and the same held true for the Hutchinsons. William was a successful and wealthy merchant, and the family built a large house in downtown Boston directly across from Winthrop's.

In his journals, Winthrop mentions Anne Hutchinson as a "goodly woman" whose devotion to scripture was admirable and who quickly became a popular and respected member of the colony as a midwife of exceptional skill. Since many women died in childbirth, and often their children as well, a midwife with a good reputation for successful births was much sought after. Anne resumed the same practice she had followed back home of holding conventicles in her home, which the women of the colony began flocking to. In time, these meetings became less Bible study and discussion and more Anne preaching her own theological views which mirrored those of Cotton, and the women began bringing their husbands to hear her preach.

Anne's sermons then began to include critiques of local pastors other than Cotton and Wheelwright, and this began her troubles with the authorities. The senior pastor of the Boston Church was John Wilson (l. c. 1588-1667 CE), who had been away in England when Cotton and then the Hutchinsons arrived. When he returned in 1635 CE, and Anne first heard him preach, she instantly dismissed him as a poor substitute for Cotton and, further, as preaching a false doctrine of works-as-justification. Wilson maintained the standard Puritan view that one could not expect God to do all the work and it was each person's responsibility to show their faith by their works as made clear in the Bible in the Book of James 2:18:

Yea, a man will say, Thou hast faith and I have works: Show me thy faith apart from thy works and I will show you my faith by my works.

Anne Hutchinson rejected this verse as advocating for works-as-justification because, to her, it was only saying the same thing Jesus conveyed in the line from Matthew 7:16: "By their fruits shall ye know them." It was obvious to Anne that Christians would show their faith through their works, but this did not mean that one's works justified one in God's eyes. Wilson and Winthrop disagreed with her interpretation; and so began the so-called Antinomian Controversy.

Antinomian Controversy & Trial

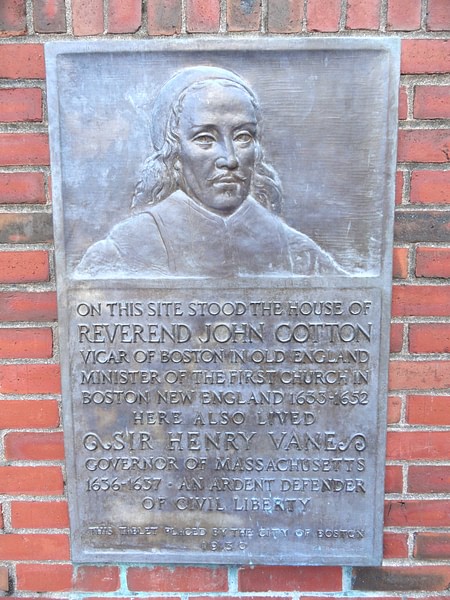

By 1636 CE, Anne Hutchinson was among the most popular citizens in the colony and was supported by Cotton and the newly arrived John Wheelwright as well as the aristocratic new governor Sir Henry Vane (l. 1613-1662 CE), who had replaced Winthrop as governor in 1636 CE and believed in religious tolerance. Vane had defended the religious reformer Roger Williams (l. c. 1603-1683 CE) earlier in 1635 CE before he was banished. Wilson and Winthrop believed that Anne Hutchinson may have bewitched Vane and the others because it was clear to them that she was able to exert some potent force which was dividing the previously unified and harmonious colony.

The authorities held a closed meeting with Anne and Cotton in December of 1636 CE and gave the impression that they were satisfied with the orthodoxy of everyone present; in reality, they were gathering evidence to be used at trial later. Anne's brother-in-law John Wheelwright was called before the court in March 1637 CE for a sermon he had given advocating the free grace of God over works. Henry Vane, who supported Wheelwright, lost the May 1637 CE election to Winthrop and returned to England, depriving Wheelwright and Hutchinson of a powerful ally. Wheelwright would be banished later that year, and Anne's own civil trial began that November. Scholar Eve LaPlante comments on its beginning:

Anne Hutchinson stood silently before the governor [Winthrop], listening closely but mindful of God. She did not yet know the nature of the charge against her. Indeed, even Winthrop himself was not yet sure what charge to use against the first female defendant in the New World. He couldn't accuse her of contempt against the state or of sedition because, as a woman, she had no public role. She could not be silenced or punished with disenfranchisement because as a woman she had no voice or vote. (12)

Throughout the three days of her civil trial, the magistrates tried to trick her into admitting to some error they could charge her with. Cotton, who was one of the judges, tried to stand up for her and act as an intermediary, but the majority were only interested in silencing her. Among these was the minister Thomas Shepard (l. 1605-1649 CE) who had earlier questioned Cotton on his own orthodoxy. The conversation which the ministers had with Hutchinson and Cotton in December 1636 CE was introduced as evidence of heterodoxy, and Anne was charged, essentially, with disturbing the peace through unorthodox views and unwarranted criticism of ministers, who were considered her spiritual superiors because they were male.

Anne Hutchinson's claim that God's grace was freely given and an individual's deeds could not merit salvation was the most difficult for the minister-judges to find fault with as it was a standard aspect of Puritan theology. They attempted to charge her with antinomianism (from the Greek "against the law"), claiming that she rejected the value of good deeds and proper behavior, but this accusation was as easily refuted as others. In response to the charge that she was preaching without authority, she rightly answered that she was only holding conventicles at her home, which was a common enough practice, and her 'sermons' were no more than observations on scripture and what the minister had preached at the day's service.

This argument led to the charge against her of undermining ecclesiastical authority by criticizing various ministers such as Wilson, which led to her statement that she had been given spiritual gifts by God and could see who was among the elect and who was not. In telling others which ministers were trustworthy shepherds and which could be safely ignored, she was only looking after their spiritual welfare. The judges then had an actual charge they could press as she was claiming knowledge only God could have: who was and was not among the elect. She was convicted, and when she asked “of what?”, she was only told that the court was satisfied of her guilt. She was placed under house arrest in the home of one of the ministers and was given an ecclesiastical trial in March of 1638 CE at which Cotton abandoned her.

Conclusion

William Hutchinson, recognizing that his wife would not back down and knowing Winthrop never would, had already made preparations for their departure. They had been invited by Roger Williams to settle near his plantation in Rhode Island, and William had been preparing the settlement with others who supported the Hutchinsons while her ecclesiastical trial was underway. The trial concluded as expected with Anne's banishment, and she left Massachusetts Bay Colony with over 60 followers who refused to denounce her.

William died in 1641 CE at about the same time as news reached the Portsmouth Colony that Massachusetts Bay Colony would be absorbing the territory. Rather than face further persecution from Winthrop, Anne Hutchinson left Portsmouth with seven of her children, a son-in-law, and servants to settle in the far more religiously tolerant Dutch New Netherlands, building a home in the area of modern-day Bronx, New York, near the landmark known as Split Rock.

She and six of her seven children, as well as others of her household, were murdered by Siwanoy Native Americans during the conflict known as Kieft's War, instigated and mismanaged by Willem Kieft (l. 1597-1647 CE), Director of New Netherlands, who had betrayed the Siwanoy's trust and attacked them. Only Anne's daughter, Susanna, survived and lived among the Siwanoy for a few years, allegedly bearing their chief a son, before she was returned to her people in an exchange of hostages at the end of the hostilities.

Winthrop and the other judges of the Massachusetts Bay Colony delighted in the news of Anne Hutchinson's end as they interpreted it as God's vindication of their verdict. Winthrop later wrote of her death, "Thus it had pleased the Lord to have compassion of his poor churches here and to discover this great imposter, an instrument of Satan" also referring to as "this American Jezebel" a reference to the 'evil' queen in the biblical book of I and II Kings (LaPlante, 244). Her name, and reputation as a divisive force, was kept alive by the transcripts of her trial and other works on that event.

The Puritans continued to revile her, but as they lost their political and spiritual hold on the region in the 18th and 19th centuries CE, Anne Hutchinson began to emerge as a religious visionary and symbol of religious freedom, who stood up to the ecclesiastical proponents of religious intolerance. The American author Nathaniel Hawthorne (l. 1804-1864 CE) modeled his heroine of The Scarlet Letter, Hester Prynne, on Hutchinson and also devoted a short story to her. In time, she came to be recognized as a powerful woman who asserted her personal dignity and rights in a time when women were given no voice to do so. The Hutchinson River and Hutchinson River Parkway in the Bronx are named for her as are many schools, parks, and memorials throughout New England. A statue honoring her stands today outside the State House in Boston, Massachusetts; the city she was once banished from.