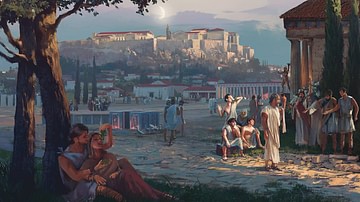

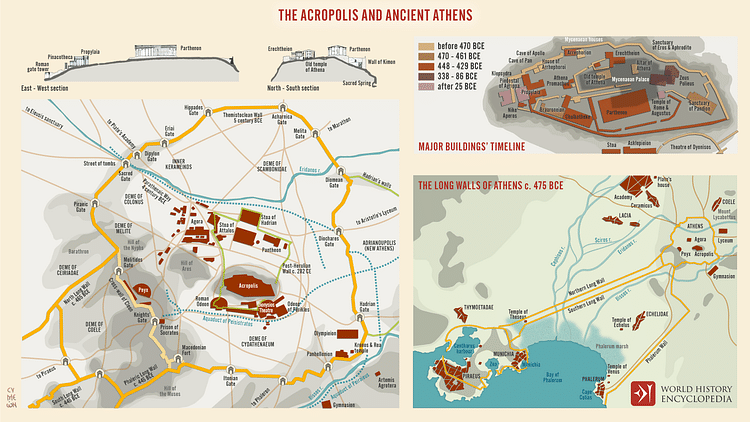

Athens, Greece, with its famous Acropolis, has come to symbolize the whole of the country in the popular imagination, and not without cause. It not only has its iconic ruins and the famous port of Piraeus but, thanks to ancient writers, its history is better documented than most other ancient Greek city-states.

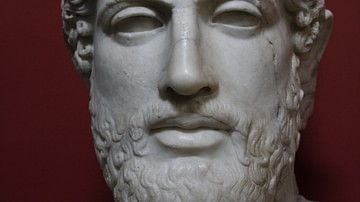

The city began as a small community of the Mycenaean Civilization (c. 1700-1100 BCE) and grew into a city that, at its height, was associated with the development of democracy, philosophy, science, mathematics, drama and literature, art, and many other aspects of world culture and civilization including the Olympic Games. The city was burned in the Persian invasion of 480 BCE, rebuilt by the statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE), and became the superpower of the ancient world through its formidable military and wealth.

It fell to Sparta after the Second Peloponnesian War (413-404 BCE) but again revived to assume a significant position of leadership among the city-states even after it was conquered by Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) in 338 BCE following his victory at the Battle of Chaeronea. The city was taken as a province of Rome after the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and became a favorite of a number of Roman emperors, especially Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE) who contributed funds and building projects to beautify it. Paul the Apostle is depicted in the Book of Acts as preaching to the Athenians, and it would later develop into an important center of Christian theology.

After Greece was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1458, Athens entered a long period of decline which was only reversed in the 19th century after the country won its independence from the Turks in 1821. Recognizing the importance of the past in maintaining national identity, the government focused on efforts to restore and preserve monuments and temples like the Parthenon as well as ancient locales like the agora. Today, Athens is the capital of Greece and among the most often visited and highly regarded cultural centers in the world.

Early Settlement & Legend

Evidence of human habitation on the Acropolis and, below, in the area around the agora, dates back to the Neolithic Period with a more advanced culture developing clearly c. 5000 BCE and, probably, as early as 7000 BCE. According to legend, the Athenian King Cecrops wanted the city named for himself but the gods, seeing how beautiful it was, felt it deserved an immortal name. A contest was held among the gods on the Acropolis, with Cecrops and the citizenry looking on, to determine which deity would win the honor.

Poseidon struck a rock with his trident, and as water gushed forth, he assured the people that now they would never suffer drought. Athena was next in line and dropped a seed into the earth which sprouted swiftly as an olive tree. The people thought the olive tree more valuable than the water (as, according to some versions of the story, the water was salty, as was Poseidon's realm), and Athena was chosen as patron and the city named for her. According to scholar Robin Waterfield:

This myth may reveal long-forgotten historical events. The ancient Greek name for Athens is a plural word, because once there were several villages which came together under the auspices of the goddess Athena – “the communities of Athena” – as it were. If the chief deity of one of these original villages was Poseidon, the myth reflects his losing out to Athena. (36)

The myth was also used, later, to justify the second-class status of Athenian women since it was the women of Athens who chose Athena’s gift over Poseidon’s and, so this justification goes, to turn away Poseidon’s wrath from the city, women’s names were not recorded on birth records as mothers (the woman’s father’s name was given) and women were denied a political voice and civic rights outside of their participation in religious activities.

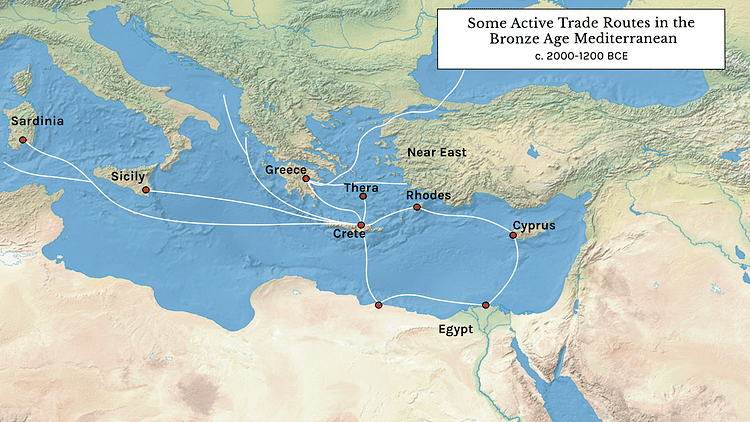

As the soil was not conducive to large-scale agricultural programs, Athens turned to trade for its livelihood and mainly to sea trade through its port at Piraeus. The early Mycenaean period saw massive fortresses rise all over Greece, and Athens was no exception. The remains of a Mycenaean palace can still be seen today on the Acropolis in the present day. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (8th century BCE) portray the Mycenaeans as great warriors and seafaring people trading widely throughout the Aegean and the Mediterranean region, and this became a point of pride for the Athenians who considered themselves direct descendants of the great Homeric heroes.

Around 1200 BCE the Sea Peoples invaded the Greek archipelago of the Aegean from the south while, simultaneously, the Dorians came down from the north into mainland Greece. While the Sea Peoples made definite incursions into Attica (the mainland region surrounding Athens) the Dorians bypassed the city, allowing the Mycenaean culture to survive (although, like the rest of Greece, there seems to have been an economic and cultural downturn following these invasions during the Bronze Age Collapse). The Athenians, afterward, claimed for themselves a special status in that they spoke Ionian, instead of Doric, Greek and held to customs they felt were more ancient and therefore superior to those of their neighbors.

Solon & the Law

The wealthy aristocrats held control of both the land and the Greek government, and, in time, poorer landowners became enslaved (or nearly so) through debt to the wealthier citizens. Further, there was a perceived lack of consistency among the other laws of the city. The first series of laws written to address these problems were provided by the statesman Draco (also given as Dracon/Drakon) c. 621 BCE but were considered too severe (the penalty for most infractions was death), and so the great lawgiver Solon (l. c. 630 - c. 560 BCE) was called upon to modify and revise them. Solon, though an aristocrat himself, created a series of laws which equalized the political power of the citizenry and, in so doing, provided the groundwork for Athenian democracy c. 594 BCE.

Solon also devoted considerable effort to making the policies of Athens not only just but profitable. He legalized prostitution in ancient Athens and taxed both individual prostitutes and brothels. As Athens was a popular and profitable trade center, many young men arrived in the city and sought the services of prostitutes while young Athenian males, who usually did not marry until after the age of 30, were provided with the means to gain sexual experience without running the risk of enraging the father and male relatives of a virgin female through pre-marital sex. By encouraging young men to visit prostitutes, Solon diffused one source of blood feuds in the city since young women of good families were understood to be off-limits to any males except the one chosen to be her husband.

After Solon resigned from public office, various factional leaders sought to seize power, and the ultimate victor, Peisistratus (d. c. 528 BCE), recognized the value of Solon's revisions and kept them, in a modified form, throughout his reign as a benevolent tyrant. His son, Hippias (r c. 528-510 BCE) continued his policies as co-ruler with his brother Hipparchus (r. c. 528-514 BCE) until Hipparchus was assassinated over a love affair in 514 BCE.

The Tyrannicides & Democracy

Hipparchus was attracted to a young man named Harmodios, but his advances were rejected because Harmodios was already involved with another man, Aristogeiton. Hipparchus did not take the rejection well and so removed Harmodios’ sister from her highly visible and prestigious position among the women of Athena's cult who participated in the Panathenaic Festival honoring the goddess. As scholar Sarah B. Pomeroy notes, "to prevent a candidate from participating in this event was to cast aspersions on her reputation" (76). Hipparchus’ removal of the girl was tantamount to claiming she was not a virgin and so insulting both her and her family. Harmodius and Aristogeiton murdered Hipparchus during the festival, were caught afterwards, and executed.

After this, Hippias became increasingly paranoid and erratic in his reign which culminated in the Athenian Revolt of 510 BCE which was actually a military action by Sparta under their king Cleomenes I (r. c. 519 - c. 490 BCE) who was invited by the Athenians to rid them of Hippias. Afterwards, the Athenians, not wanting to be obliged to Sparta, rewrote their history casting Harmodios and Aristogeiton as "the tyrannicides" who had struck the first blow for freedom and restored the democratic ideals of the city. Actually, they had done neither; they were simply avenging a personal insult.

In the aftermath of the coup, and after settling affairs with various factions, the statesman Cleisthenes (l. 6th century BCE) was appointed to reform the government and the laws and, c. 507 BCE, he instituted a new form of government which today is recognized as democracy. Cleisthenes is regarded as the "Father of Athenian Democracy", but this form of government was significantly different from how democracy is understood in the present day. In Athenian democracy, only upper-class male citizens had a political voice, disenfranchising women, foreigners, and, of course, the many slaves who made up a large part of Athens’ population.

Even so, this new form of government involved the citizenry directly in political decisions, and even those who were not allowed to vote understood that decisions were being made now by a majority of informed citizens rather than a tyrant. Athenian democracy would provide the stability necessary to make Athens the cultural and intellectual center of the ancient world; a reputation that lasts even into the modern age. Waterfield comments:

The pride that followed from widespread involvement in public life gave Athenians the energy to develop their city both internally and in relation to their neighbors. (62)

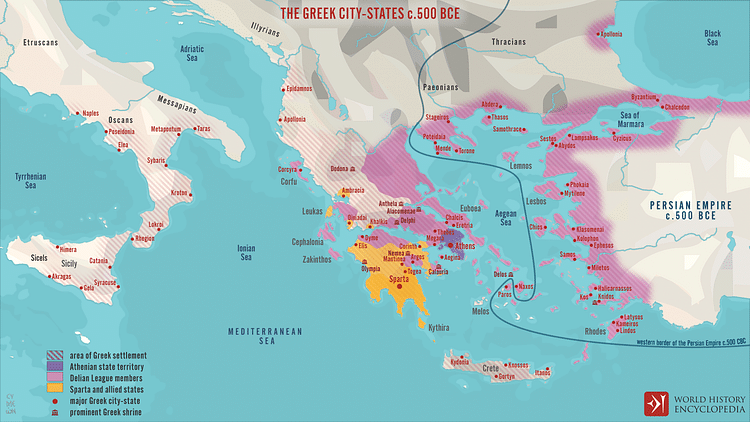

Believing themselves descended from great heroes, and with heroes in their midst like the tyrannicides, the Athenians understood they now had the best form of government which they should encourage elsewhere; so they decided to incite the Greek communities of Asia Minor, then under the control of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) to revolt.

The Persian Wars

The Persian Empire at this time was led by the emperor Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) who quickly crushed the rebellion and then sent a force against Athens. The Persians were defeated at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, losing over 6,000 men to the brilliant tactics of the Athenian general Miltiades (l. 554-489 BCE) whose losses numbered only 192 soldiers. The Persian military was considered invincible at this time and so this victory increased the Athenians’ already high opinion of themselves.

In 480 BCE, however, Darius I’s son and successor, Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) assembled the largest army mustered in the world up to that time and launched an invasion of Greece, with Athens as the primary target, to avenge the insult to his father. His forces were held at Thermopylae by the Spartan king Leonidas (d. 480 BCE) and his famous 300 warriors but, after defeating and killing them, Greece lay open for conquest.

The Persian navy was defeated by the Athenian-led forces at the Battle of Salamis, however, when the Athenian general Themistocles (l. 524-460 BCE) outmaneuvered and outfought them, and this defeat was followed by the land battles of Plataea and Mycale in 479 BCE which drove the Persians from Greece and established Athens as a superpower. Waterfield notes:

This was Athens’ finest hour. Themistocles was the acknowledged savior of Greece, and the city expressly waved the banner of panhellenism, both by expressing what was common to all Greeks and by continuing the fight against the Persians. From obscure origins, a small and impoverished city had risen to power and prominence. (72)

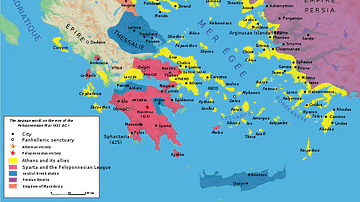

Under Pericles, Athens formed the Delian League, ostensibly to create a cohesive Greek network among city-states to ward off further Persian attacks. The other city-states paid into the treasury of the Delian League and Athens agreed to protect them against Persian aggression in return. Pericles used the money from the league to beautify and fortify Athens and, under his leadership, the city grew so powerful that the Athenian Empire could effectively dictate the laws, customs, and trade of all its neighbors in Attica and the islands of the Aegean.

The Golden Age

Under Pericles, Athens entered its golden age and great thinkers, writers, and artists flourished in the city. Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/423 BCE), the "father of history", lived and wrote in Athens. Socrates (l. c. 470/469-399 BCE), the "father of philosophy", taught in the marketplace. Hippocrates (l. c. 460-370 BCE), 'the father of medicine', practiced there. Phidias (l. 480-430 BCE) created his great works of Greek sculpture for the Parthenon on the Acropolis and the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.

Democritus (l. c. 460 - c. 370 BCE) envisioned an atomic universe. Aeschylus (l. c. 525 - c. 456 BCE) Euripides (l. c. 484-407 BCE), Aristophanes (l. c. 460 - c. 380 BCE) and Sophocles (l. 496 - c. 406 BCE) made Greek drama, both comedy and tragedy, famous, and the lyric poet Pindar (l. c. 518 - c. 448 BCE) another important figure of Greek literature, wrote his Odes. This legacy would continue as Plato (l. 424/423-348/347 BCE) would found his Academy outside the walls of Athens in 385 BCE and, later, Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) would establish his school of the Lyceum in the city center.

The might of the Athenian Empire encouraged an arrogance in the policymakers of the day which grew intolerable to its neighbors. When Athens sent troops to help Sparta put down a Helot rebellion, the Spartans refused the gesture and sent the Athenian force back home in dishonor, thus provoking a war which had long been brewing. Later, when Athens sent their fleet to help defend its ally Corcyra (Corfu) against a Corinthian invasion during the Battle of Sybota in 433 BCE, their action was interpreted by Sparta as aggression instead of assistance, as Corinth was an ally of Sparta.

Conclusion

The First Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) between Athens and Sparta (though involving, directly or indirectly, all of Greece) ended in a truce between the parties involved, but Athens was defeated in the Second Peloponnesian War and fell from its height of power. The empire and the city’s wealth gone, the walls destroyed, only its reputation as a great seat of learning, Greek philosophy and culture prevented the sack of the city and the enslavement of the populace. Athens struggled to throw off this condition as a subject state, and with some success, until they were defeated in 338 BCE by the Macedonian forces under Philip II at Chaeronea.

Athens was then subject to Macedonian rule until their defeat by the Romans in 197 BCE at the Battle of Cynoscephalae after which Greece was methodically conquered by the Roman Empire. It is a tribute to the enduring reputation of Athens as a cultural center that the Roman general Sulla, who sacked the city in 87-86 BCE, slaughtered the people, destroyed the agora, and burned the port of Piraeus, always maintained his innocence, claiming he had ordered his men to treat the city well and they simply had failed to heed him.

According to the biblical Book of Acts, Saint Paul preached to the Athenians at the Areopagus (the hill of Mars), praising their interest in religion and telling them about the new god Jesus Christ. After the rise of Christianity following its adoption by the Roman Empire, Athens became an important center for the new faith and, in the 6th century CE, pagan schools were closed and temples either destroyed or converted into churches.

The city was sacked by a number of so-called "barbarian tribes" in Late Antiquity up through the Middle Ages until it was established as the Crusader State of the Duchy of Athens (1205-1458) after the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204). Athens did well during this period until it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1458. The Ottoman Turks had no respect for the ancient city, and it steadily declined under their control.

After Greece won its independence from the Turks in 1821, Athens again revived just as it had done many times in the past. Restoration and preservation efforts became a priority of the new government, and the city was restored to some semblance of its ancient grandeur. In the present day, the name of Athens still conjures to the mind images of the classical world and the heights of intellectual and poetic creativity, while the Parthenon on the Acropolis continues to symbolize the golden age of ancient Greece and the best of what it stood for.