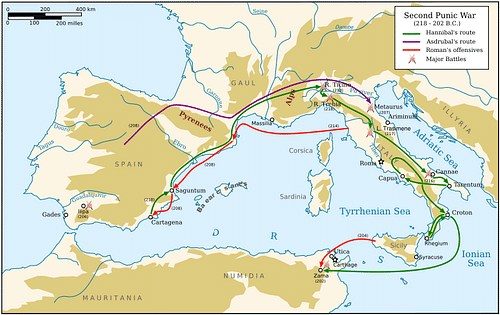

The Battle of the Metaurus (207 BCE) was a military engagement fought between the forces of Rome under Gaius Claudius Nero (c. 237 - c. 199 BCE), Marcus Livius Salinator (254-204 BCE), and L. Porcius Licinius and the Carthaginians under Hasdrubal Barca (c. 244-207 BCE). Nero's forces defeated Barca who was killed in the battle. The two armies met after Hasdrubal had crossed the Alps into Italy to join his forces with those of his brother Hannibal (247-183 BCE) for a united attack on the city of Rome in hopes of ending the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) between Rome and Carthage. Had he succeeded, Rome might have fallen to the Carthaginians and the war would have ended quite differently but this, of course, is speculation.

Roman writers and historians since the time have suggested that Hasdrubal probably would have successfully reached Hannibal – avoiding the conflict at the Metaurus River – if he had not delayed in his march to try to reduce the Roman colony of Placentia. Hasdrubal's whole purpose in coming to Italy was to reinforce his brother for a united push against Rome, not to conquer Roman positions on his own, but he may have felt he could not leave a fortified Roman colony to the rear of his army and tried to take it through siege.

The siege failed and the delay allowed for a Roman force led by L. Porcius Licinius and Marcus Livius Salinator to check him near the Metaurus. Nero, acting swiftly on intelligence reports, joined these generals and convinced them to attack Hasdrubal at once, resulting in a Roman victory and preventing Hannibal from receiving the reinforcements he needed to attack Rome.

Without Hasdrubal's army, Hannibal was forced to continue attempts to win the cities of Italy to his cause and defeat the Romans in the field. His Italian campaigns ended when he was recalled to Africa to defend Carthage against an advance by the Roman general Scipio Africanus (236-183 BCE) who defeated him at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE, winning the war for Rome.

The Second Punic War

The Second Punic War was a direct result of the First Punic War (264-241 BCE) which was also won by Rome. After the First Punic War, Rome imposed heavy fines in the form of tribute on Carthage, which the city struggled to pay. They drew on their colonies in Spain for resources and sent their premier general, Hamilcar Barca (275-228 BCE) to the region in 237 BCE to keep the peace among the tribes there and also make sure that Rome made no incursions into Carthaginian territory. Hamilcar took his son Hannibal along with him as well as his son-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair (c. 270-221 BCE). When Hamilcar was killed at the Battle of Helice in 228 BCE, fighting against native tribes, Hasdrubal the Fair took command of the Carthaginian forces.

Hasdrubal the Fair was more inclined to negotiations than battle and was able to maintain cordial relations with Rome. He set the boundary in Spain between Roman and Carthaginian territories at the Ebro River and this was agreed to by the Romans. Hasdrubal the Fair was assassinated in 221 BCE and the soldiers unanimously voted for Hannibal to take command. Hannibal was literally a sworn enemy of Rome, having been so sworn by his father who had fought the Romans in the First Punic War. Hannibal had no interest in negotiating anything with the Romans and even less in continuing to pay the humiliating tribute which so heavily taxed Carthage.

When the Romans installed an anti-Carthaginian government in the Spanish city of Saguntum, Hannibal seized on it as an excuse for war. A Roman delegation came to him asking him to leave Saguntum alone but Hannibal, presenting himself as a liberator of the people, claimed that Rome could not be trusted to deal fairly with the city, dismissed the delegation with a refusal, and marched on Saguntum, taking it; this was the first action of the Second Punic War.

Hannibal in Italy & Hasdrubal in Spain

Hasdrubal Barca had been in Spain since at least 228 BCE as he is mentioned as being present with Hannibal at the death of their father at Helice. Once Saguntum was taken, Hannibal informed his commanders – Hasdrubal among them – that the only way to win the war was to take the fight to the enemy and he was going to do just that. In April 218 BCE he crossed the Alps with his army into Italy and began a campaign of conquest and conciliation. He left Hasdrubal in charge of his armies in Spain. Scholar Rose Mary Sheldon comments:

Most of Italy at this time was not yet Roman territory but a conglomeration of independent, autonomous states joined under Roman primacy. Hannibal, devising his own brand of psychological warfare, strove to drive a wedge between Rome and the other indigenous communities of Italy. From his first appearance on Italian soil, he announced that he had come not to fight against the peoples of the peninsula, but to liberate them from Roman domination. After every battle he released without ransom any non-Romans who had been taken prisoner, so that they would spread the word in their native regions about Hannibal's political goals and his generosity. (48)

His strategy was immensely successful. He won the Battle of Ticinus in November and the Battle of Trebia in December 218 BCE and won more people to his cause. In 217 BCE he was again victorious in every engagement, most notably the Battle of Lake Trasimene in June. By 216 BCE he was able to threaten Rome itself and, in August, won his most famous victory at Cannae.

While Hannibal was marching through Italy, Hasdrubal was holding against the Roman forces in Spain. Shortly after Hannibal left for Italy, Hasdrubal created a defense system of watchtowers and walls which alerted him to the approach of any Roman navy landing an invasion force. In the fall of 218 BCE, however, Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio (265-211 BCE) was able to establish himself in Spain and soon after defeated the Carthaginian commander Hanno at the Battle of Cissa. This victory allowed the Romans a significant base from which to launch further campaigns in the region.

Hasdrubal arrived too late at the battle to help Hanno and so concentrated his attention on the Roman ships, destroying almost half of them before retreating. In 217 BCE he engaged the Romans in a naval battle on the Ebro River which seemed promising owing to his larger fleet and the past success of Carthaginian naval tactics. However, the Romans had allies from Marseille, who knew the strategies Carthage had used in the past and turned their tactics against them. Hasdrubal lost most of his fleet and retreated without offering further battle on land.

Scipio's brother, Publius Cornelius Scipio (died 211 BCE) then joined him in Spain with reinforcements and presented a much more serious threat to Hasdrubal. They took Saguntum and released the hostages the Carthaginians had taken from local tribes to ensure their compliance. This action won the Romans larger support and a number of tribes rebelled against Carthaginian domination. Hasdrubal needed to spend most of 216 BCE putting down revolts, which gave the Scipio brothers more time to prepare.

In 215 BCE, the Carthaginian senate sent word that Hasdrubal should join his brother in Italy. Hasdrubal began the march but, at the Battle of Dertosa, was met and defeated by the Scipios. Hasdrubal retreated and Roman power in Spain was increased. Following this defeat, the Carthaginian senate sent Mago Barca (243-203 BCE) and Hasdrubal Gisco (died 202 BCE) to Spain with reinforcements.

Hasdrubal Barca, Hasdrubal Gisco, and Mago kept the Scipios busy but could not beat them; every engagement was a Roman victory. In 213 BCE Hasdrubal was withdrawn from Spain to put down an offensive by the Numidian king Syphax (an ally of Rome) in Africa – an uprising allegedly engineered by the Scipios to draw Hasdrubal away; if so, they never took advantage of his absence.

Hasdrubal returned to Spain in 211 BCE with fresh reinforcements and supplies and met the Romans in battle, dividing his army between his own command and that of Mago and Gisco. The Scipios, perhaps unaware of how large an army was assembled, divided their forces; Publius directed his army toward the lines of Mago and Hasdrubal Gisco while Gnaeus went to meet those of Hasdrubal Barca in another area. Hasdrubal bribed the Celtiberian mercenaries of Gnaeus' army to abandon the Romans and go home; this they promptly did, reducing Gnaeus' forces even further. The Scipios were defeated and killed in the ensuing Battle of the Upper Baetis and the Roman army was scattered. It was a major victory for Carthage and a shattering defeat for Rome.

Nero & Scipio Africanus

This win for Carthage, however, would bring two Roman leaders to the forefront whose brilliance and decisiveness would be the doom of Carthage: Gaius Claudius Nero and Scipio Africanus. Both men had already faced Hannibal in Italy – Scipio had survived the Battle of Cannae – and knew his tactics and also, possibly, those of his brother. When the Scipio brothers were killed, no Roman leader wanted to take their place in Spain but Scipio volunteered. Nero was transferred from Italy.

Scipio began his war in Spain with the brilliant capture of New Carthage while Nero did not fare as well. Nero had Hasdrubal pinned down at Black Stones Pass but the Carthaginian general asked for negotiations over several days to work out the details of surrender and safe passage for his army. Every night, after the meetings, he would send more and more of his men secretly out of camp and to safety; finally, on a particularly foggy morning, he packed up the entire camp and slipped away. Nero was then recalled to Italy and Scipio conducted operations in Spain.

Events did not go well for Hasdrubal once Scipio was in charge. The Carthaginians finally made a stand at Baecula in 208 BCE in a well-fortified position above a river which would require Scipio to charge uphill against a heavily-defended position. Scipio sent only a light contingent in the center against the Carthaginian lines and, when the enemy moved against them, drove his heavy infantry up two gulleys on either side of the opposing lines, crushing the flanks and winning the day. Hasdrubal escaped from the battle and led what was left of his army toward the Alps to join his brother in Italy.

The Battle of the Metaurus

Once across the mountains, Hasdrubal began his march south to join Hannibal but stopped to attempt the taking of the colony of Placentia. Scholar Ernle Bradford comments:

Crossing the Po and mastering the Stradella pass, he parched against Placentia. Here he faltered and lost time, laying siege to this faithful Roman colony which had closed its gates against him, having taken note of the fact that, like Hannibal, he had no equipment to conduct a siege. Hasdrubal has been blamed by some historians for delaying at Placentia, instead of bypassing it and marching on to rendezvous with his brother before the Romans could collect all their forces together. He was faced, however, with the fact that Placencia seemed a very strong garrison to leave in his rear and – even more important perhaps – the local Gallic tribes were slow to rise in his favor. He needed to wait until sufficient Ligurians had reached him and as many Gauls as possible had been recruited. (171)

His siege of Placentia was a failure for the very reason the citizens counted on: he had no siege engines, no catapults, nothing by which he could reduce a city. He marched on from Placentia and headed south while, at the same time, Hannibal was being harried by Hasdrubal's old enemy Claudius Nero. Nero had been sent against Hannibal soon after his redeployment to Italy and was now playing a kind of cat-and-mouse maneuver with him near Bruttium.

Hasdrubal's march led him into the path of the armies of Marcus Livius Salinator and L. Porcius Licinius near the Metaurus River. The two armies were fairly evenly matched, however, and held off from engaging. Shortly before this meeting, Hannibal had sent messengers north to locate Hasdrubal and urge haste in reaching him. The messages were received and Hasdrubal wrote back telling Hannibal where he was and also the size of his army. He sent the messages by six horsemen who were captured by Roman sentries near Tarentum. Since the letters were not written in any kind of code, they were easily translated from the native Punic and this intelligence was sent quickly to Nero's camp.

Nero acted swiftly without waiting for senatorial approval from Rome. Screening his movements at night, he slipped away from Hannibal with 6,000 legionaries and 1,000 cavalry and quick-marched them to the camp of Porcius and Salinator. Since the Roman camp was located only about a half mile away from the Carthaginians, Nero had his men billeted with those already there so no new tents would betray his presence.

The next morning, Hasdrubal was mobilizing his forces for battle when he noticed leaner horses in the enemy camp and strange shields on display. He sent scouts to reconnoiter, and they returned to report that nothing was any different than it had been but they had observed that one trumpet sounded the morning orders in the praetor's camp – as usual – but two had sounded in the consul's camp, indicating the presence of a second consul and so, certainly, his army. Hasdrubal understood he was now facing a much larger force and ordered his men to stand down from the attack.

That night, he retreated from his position toward the Metaurus River, most likely planning to cross it the next morning. Exactly what he intended to do after that is unknown because it is thought that he was demoralized by the possibility that his brother had been killed in battle. Whoever the unknown consul was who had joined with the others opposing him, he certainly would have been previously occupied by Hannibal. The consul would not have disengaged with Hannibal to come after him unless Hannibal was dead. Hasdrubal may have thought he was now alone against overwhelming forces in a foreign land.

His army, moving toward the Metaurus, got lost in the darkness and morning found them strung out along the river in disorder. Nero, back in the Roman camp, saw the opportunity and – against the counsel of the other two – pressed for an immediate attack. The Romans marched toward battle as Hasdrubal drew up his forces as best he could and the two met in battle. Hasdrubal placed his Gauls on a small hill on his left, his Spaniards and Ligurians in his center where he also placed ten elephants, and his cavalry was on the right wing. The Romans deployed with Salinator in the center, Porcius on the left, and Nero on the right facing the Gauls on their hill which was protected by uneven terrain.

Hasdrubal's elephants caused more harm than good because the Romans understood, after encounters with Hannibal, that elephants could be turned into a liability for the opponent when wounded; the Romans attacked them with spears and they rounded on the Carthaginian troops. Salinator and Porcius pressed the center and the left but Nero could not manage to dislodge the Gauls from their hill.

Recognizing that the battle could be won by a concerted charge at the other end of the line, he pulled his troops from engagement with the Gauls and moved them swiftly behind the Roman lines to come down on the left – the right wing of the Carthaginians – breaking the line and driving Hasdrubal's troops into a rout which swiftly became a massacre. Hasdrubal's army tried to retreat across the Metaurus but they were either drowned or cut down by the Romans. Recognizing that he was defeated, and that his brother was most likely dead somewhere in the south, Hasdrubal drove his horse onward into the enemy lines swinging his sword and was killed.

Once the battle was over, Nero swiftly assembled his troops and marched them back south to again engage Hasdrubal's brother. Hannibal never knew he had left. The first Hannibal knew of his brother's defeat – or even whereabouts – was when a Roman cavalry contingent threw Hasdrubal's head into his camp near Bruttium.

Conclusion

The Battle of the Metaurus is a significant part of one of the great What-Ifs of history. Even though Hannibal and Hasdrubal had no siege engines nor any means of taking a city, it is likely that, had they concentrated their combined forces in an assault on Rome, the city would have surrendered and Carthage would have won the war. Hannibal was undefeated in Italy and Hasdrubal was known as the general who had defeated and killed two of the greatest Roman generals of their generation. Rome had already panicked when Hannibal had won at Cannae in 216 BCE and certainly would have been prone to do so again.

What if Hasdrubal had not lingered at Placentia? What if he had not sent the letters in Punic which alerted Nero of his location? Or what if he had simply given the messages to the riders verbally instead of in written form? What if he had charged the Roman camp instead of retreating when he sensed Nero's presence?

All such questions, however fascinating, are ultimately unanswerable. Hasdrubal's choices led him to the encounter at the Metaurus, and afterwards there were no longer any options for Hannibal except to fight a losing war against overwhelming odds which would end in his defeat. The Carthaginian senate refused him any more troops or supplies, and when Scipio Africanus proposed his plan to attack Carthage and draw Hannibal out of Italy, it worked as perfectly as he had planned. Hannibal was defeated at the Battle of Zama and, afterwards, more or less lived a life on the run from the agents of Rome until he took his own life at the age of 65 in a country far from his home.