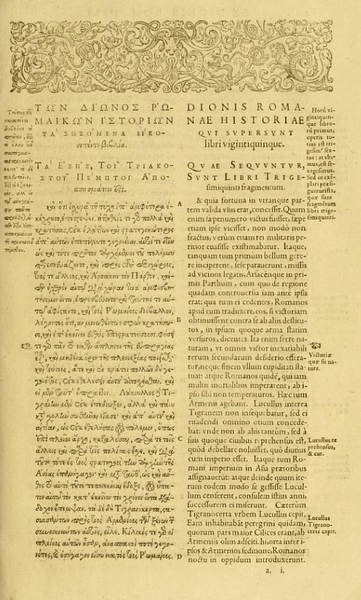

Cassius Dio (c. 164 - c. 229/235 CE) was a Roman politician and historian. Although he held a number of political offices with distinction, he is best known for his 80-volume Roman History. The work took 22 years to complete, was written in Attic Greek, and follows Roman history from the city's foundation to the reign of Alexander Severus (r. 222-235 CE). Unfortunately, only one-third of Cassius Dio's Roman History survives, the best-preserved part being the period 69 BCE - 46 CE.

Early Life & Political Career

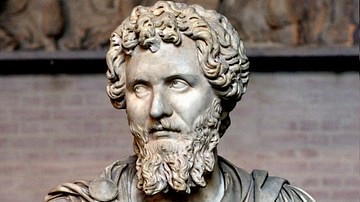

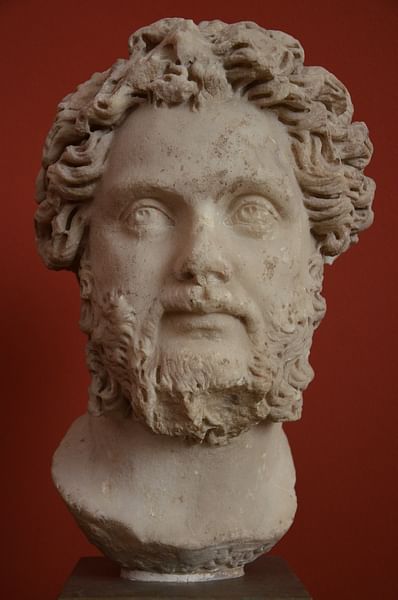

Born around 164 CE, Cassius Dio came from a prominent family of the city of Nicaea in Bithynia, learning to speak both Greek and Latin. Most of what is known of his early life and career comes from his personal writings. His father, Cassius Apronianus, had a distinguished career, serving as a senator, consul, and governor of Lydia, Pamphylia, Cilicia, and Dalmatia. After arriving in Rome around 180 CE (the date is in dispute), Cassius Dio, like his father, entered the cursus honorum and had a life-long career in the Roman government, even accompanying his father to Cilicia as a young man. He served as a quaestor at the age of 25, a praetor in 194 CE (appointed by Roman emperor Septimius Severus, r. 193-211 CE), a suffect consul in 204 CE, accompanied Emperor Caracalla (r. 211-217 CE) on his eastern tour in 214 and 215 CE, and was named curator of Pergamon and Smyrna by Emperor Macrinus in 218 CE.

He also served as proconsul of Africa, legate of Dalmatia and Upper Pannonia, and before retiring to his home in Bithynia, he held a second consulship in 229 CE with Emperor Alexander Severus. In his Roman History, he wrote of his career as a consul and legate:

Thus far I have described events with as with great accuracy as I could in every case, but for subsequent events I have not found it possible to give an accurate account, for the reason that I did not spend much time in Rome. For, after going from Asia into Bithynia, I fell sick, and from there I hastened to my province of Africa; then, on returning to Italy I was almost immediately sent as governor first to Dalmatia and then to Upper Pannonia, and after that I returned to Rome and Campania. I at once set out for home. (Book 80, p. 481)

Roman History

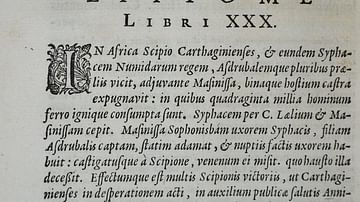

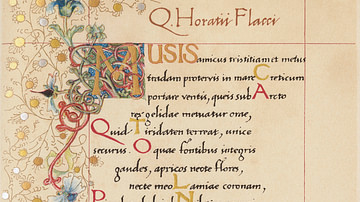

Despite his illustrious political career, Cassius Dio is best known for his 80-volume Roman History. Written chronologically, it is a history that follows Rome from its early foundation through the reign of Alexander Severus. Prior to beginning his Roman History around 202 CE, however, he first wrote two short pieces: one on the rise of his close friend Emperor Septimius Severus and the second on the wars that followed the death of the much-despised Emperor Commodus. Written in Attic Greek, his history would take him ten years of research and then twelve additional years of writing. Unfortunately, much of his voluminous work is lost with only one-third in existence. Luckily, the period 69 BCE - 46 CE has been preserved through the writings of later historians such as the Byzantine authors Zonares and Xiphilinus.

While he rarely cited his sources, it is quite evident that he borrowed from the works of the Greek historian Thucydides and others. He even copied Thucydides' historical perspective. For the early years of Rome, he relied on both literary sources and public documents. However, he drew on his personal experiences in the political arena when writing on his own time period. These turbulent times - a time of both praise-worthy and tyrannical emperors - included the reigns of Commodus, Pertinax, Didius Julianus, Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Geta, Elagabalus, and Alexander Severus. In an attempt to explain the purpose of his history, Cassius Dio addresses the reader in the opening pages of Volume One. According to an excerpt from the Roman History found in the works of Zonares, Cassius wrote:

It is my desire to write a history of all the memorable achievements of the Romans, as well in time of peace as in war, so that no one, whether Roman or non-Roman, shall look in vain for any of the essential facts. (Book 1, p. 3)

Although he is criticized by some for errors, distortions and omissions, Cassius Dio later wrote explaining both his sources and his work's reliability:

Although I have read pretty nearly everything about them [the Romans] that has been written by anybody, I have not included it all in my history, but only what I have seen fit to select. I trust, moreover, that if I have used a fine style, so far as the subject matter permitted, no one will on this account question the truthfulness of the narrative … (Book 1, p. 3)

He chose to begin his "narrative" where he had obtained the "clearest accounts of what is reported to have taken place in this land which we inhabit." (Book 1, p. 3)

Content

Unlike his contemporaries, Cassius Dio dated the start of the Imperial Period from 31 BCE and the accession to the throne of Augustus (Octavian) while others, such as Suetonius in his Twelve Caesars, chose to begin with the dictatorship of Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE). In his history, Cassius Dio wrote on the rise of the Roman Empire:

In this way the power of both the people and senate passed entirely into the hands of Augustus, and from his time there was, strictly speaking, a monarch, would be the truest name for it, no matter if two or three men did later hold power the same time. The name, monarchy, to be sure, the Romans so detested that they called their emperors neither dictators nor kings nor anything of the sort; yet since the final authority for the government devolves upon them, they must needs be kings. (Book 53, p. 237)

He added that emperors assumed the titles and functions of the office of the old Roman Republic. The change of the republic to the empire dominated his writings. The monarchy provided Rome with a stable government. Years later during the "tyrannical period," people recalled the reign of Augustus as being one of moderate freedom, free of civil conflict.

Cassius Dio even wrote on how one could be a good emperor: a good emperor should not act with excess or degrade another. He should address others as his equal. He must be seen as virtuous and peaceful but still good at warfare. In this way, he will be seen as both a savior and father. Of course, he admired Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE), believing his wife Livia was highly influential:

Augustus attended to all the business of the empire with more zeal than before, as if he had received it as a free gift from all the Romans, and in particular he enacted many laws. I need not enumerate them all accurately one by one, but only those which have a bearing upon my history…. He did not, however, enact all these laws on his sole responsibility, but some of them he brought before the public assembly in advance, in order that, if any features caused displeasure, he might learn it in time and correct them; for he encouraged everybody whatsoever to give him advice…. (Book 53, p. 249)

He admired Emperor Claudius (r. 41-54 CE) for having a keen intelligence and his love of history and languages. He praised such emperors of Pertinax (r. 193 CE) who had his throne usurped by Didius Julianus (r. 193 CE). In the Roman History, Pertinax is depicted as being formidable in war and shrewd in peace. It was Pertinax who initially named Cassius Dio as a praetor. The Stoic Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE) is applauded for his sense of duty, laboring into the night to complete the day's work. However, he criticized the eccentric behavior of Elagabalus (r. 218-222 CE) and excesses of Commodus (r. 180-192 CE). Throughout his writings, his treatment of individual emperors reflects his personal values and interests. And, like other Roman authors and historians, it is evident that he believed in the prominence of divine direction.

He saved his criticism for both Emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE), who he accused of starting the great fire, and Commodus. On the death of Nero's mother Agrippina, Cassius Dio wrote:

This was Agrippina, daughter of Germanicus, grand-daughter of Agrippa, and descendant of Augustus, slain by the very son to whom she had given the sovereignty, and for whose sake she had killed her uncle and other. Nero, when informed that she was dead, would not believe it, since the deed was so monstrous that he was overwhelmed by incredulity, he therefore desired to behold the victim of his crime with his own eyes. So he laid her body bare, looked her all over and inspected his wounds, finally uttering a remark far more abominable even than the murder. (Book 62, p. 67-68)

Dio added that the grieving emperor gave the Praetorian Guard money, inspiring them to commit other such crimes. He also wrote a letter, although it was actually written by his tutor Seneca, to the Roman Senate naming a number of crimes committed by his mother - one being a plot against him. The haunting vision of his dead mother caused several restless nights for the young emperor.

Cassius Dio also accused Nero of setting the fire that destroyed much of the city. According to Cassius Dio, the emperor secretly sent out men who pretended to be drunk and caused them to set fire to several buildings in different parts of the city.

The historian saved much of his criticism for Emperor Commodus (r. 180-192 CE) who he accused of unseemly deeds. Cassius agreed with others that Commodus was both immoral and ruthless. However, he wrote:

This man was not naturally wicked, but, on the contrary, as guileless as any man that ever lived. His great simplicity, however, together with his cowardice, made him the slave of his companions and it was through them that he at first, out of ignorance, missed the better life and then was led on into lustful and cruel habits, which soon became second nature. (Book 72, p. 73)

Cassius Dio told of the emperor's obsession with his skill in the arena and the delight he took in killing animals. He related an instance that he personally witnessed. Commodus, who considered himself another Hercules, had killed an ostrich on a hunt and then imitated the victorious pose of a gladiator. Cassius Dio had difficulty to keep from laughing. The emperor's death was considered a relief.

Although he was very close to Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE), he remained critical. He admired the emperor's intelligence, industry, and thrift. However, he criticized Septimius Severus' treatment of the Senate, and like other historians, Cassius Dio believed many of the disasters that followed were due to the emperor's policies. He praised the kindness of the emperor for his treatment of the fallen Pertinax. Severus ordered a shrine to be built to honor the usurped emperor and ordered that his name be mentioned in the close of all prayers. On his deathbed, it is said Severus advised his sons, Caracalla and Geta, to be "one with each other," be generous to the troops, and not care for anybody else.

The Roman History only gives cursory coverage of the reign of Alexander Severus, for Cassius Dio was not in Rome for much of it. However, he still witnessed the hostility aimed at the young emperor. One of his last entries speaks of his visit with the emperor. He wrote:

[The young Alexander] …honoured me in various ways, especially by appointing me to be consul for the second time, as his colleague…he bade me to spend the period of my consulship in Italy, somewhere outside Rome. And thus later I came both to Rome and to Campania to visit him, and spent a few days in his company…then, having asked to be excused because of the ailment of my feet, I set out for home, with the intention of spending all the rest of my life in my native land, as, indeed, the Heavenly Power revealed to me most clearly when I was already in Bithynia. (Book 80, p. 485)

The exact date of his death is unknown. Some guess it as late as 235 CE, while others only speculate that it had to be after 229 CE, the date of his last consulship.