Constantine X Doukas was the ruler of the Byzantine Empire from 1059 to 1067 CE. During his reign, the Byzantine Empire was attacked by emerging enemies on all sides, including the Normans in Italy and the Seljuk Turks in Armenia and Anatolia. Constantine's policies isolated the Monophysite Armenians, downsized the army at the worst possible moment, and contributed to the general decline of Byzantium during the second half of the 11th century CE. Although Constantine was a poor emperor, it was his successors who would have to bear his unhelpful legacy.

Succession & Reign

Constantine was from a powerful landed family in Anatolia and was connected through marriage to other leading Byzantine families. For example, he was married to Eudokia Makrembolitissa, the niece of Michael Keroularios, the Patriarch of Constantinople. Constantine had been imprisoned by John the Orphanotrophus, the effective power behind the throne, back during the reign of Michael IV the Paphlagonian (r. 1034-1041 CE) for supporting a suspected rebel. However, Constantine disappeared from the historical record for the next two decades, which saw the final end of the ruling Macedonian Dynasty in 1056 CE and the emergence of a period of uncertainty as to who would rule Byzantium. Constantine supported Isaac I Komnenos (r. 1057-1059 CE) during his rebellion against Michael VI (r. 1056-1057 CE), but it is unclear what position, if any, he held in Isaac's administration. When Isaac lay dying two years later, he appointed Constantine as his successor, possibly through the machinations of the minister and historian Michael Psellos, whose history is in large part a panegyric of the Doukas family.

Constantine was careful to cultivate a popular image for himself in the capital through adjudicating legal cases himself, presenting himself as pious, and restoring the honors and salaries to those who had lost them during Isaac's reign. Unlike Isaac, Constantine was not fiscally conservative. In a baffling and very untimely move which ultimately had disastrous consequences, he downsized the armies to cut costs in 1059 CE, at the exact time when powerful new enemies – the Pechenegs, Normans, and Seljuk Turks – were attacking the Byzantine Empire.

In 1060 CE, a group including the prefect of Constantinople and other imperial officials devised an elaborate plot to assassinate Constantine. He barely managed to escape, but his brother John was able to restore order in the aftermath. While the successful liquidation of the coup attempt helped solidify his rule, it also demonstrated the fragility of Constantine's early rule.

Constantine's piety led him to intensify persecutions against non-Orthodox Christians, namely the Monophysites, who had differing beliefs about the nature of Christ. The Patriarchs Constantine Leichoudes and John Xiphilinos willingly aided Constantine's policies, exiling or imprisoning leading Monophysite churchmen and threatening Monophysites in the eastern provinces such as the city of Melitene. Eventually, this policy would backfire by cooling Monophysite support for Byzantium. In the Byzantine Empire, Monophysites were primarily Armenians residing in the eastern provinces bordering the Seljuk Turks' expanding empire. When the Seljuk Turks continued to raid deeper and deeper into Anatolia, the loss of Armenian support was a serious handicap, especially in combination with Constantine's shrinking of the armies.

Foreign Invasions

The historical narrative is lacking on the exact movements of the Seljuk Turks during Constantine's reign, but they undoubtedly continued to probe deeper and deeper into Byzantine Anatolia, no doubt aided by the downsizing of the armies. However, there were reprisals for the Turks. One force, after attacking Byzantine cities, was tracked and defeated by a Byzantine force under the Duke of Edessa and Hervé Frangopoulos, a Norman mercenary general in Byzantine hire. However, the duke was killed in the battle and Frangopoulos was executed for treasonous behavior.

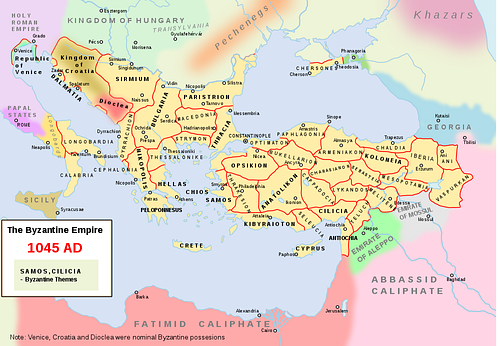

In 1064 CE, Alp Arslan (r. 1063-1072 CE) became the Seljuk sultan. Wanting to demonstrate that he was just as powerful as his predecessor, his uncle Tughril (r. 1037-1063 CE), Alp Arslan led a force into Byzantine Armenia. His forces captured Byzantine forts, forced Bagrat IV of Georgia (r. 1027-1072 CE) to submit, and then converged on the former Armenian capital of Ani. Ani and the Kingdom of Armenia, the largest of the Armenian kingdoms, had been annexed by the Byzantine Empire in 1045 CE. It had strong defenses, and under normal circumstances, Ani's walls would have held off the Seljuks. However, Constantine had appointed a governor who did not maintain the defenses and skimped on paying troops. On 16 August 1064 CE, some of the defenders abandoned their posts and the Seljuks then sacked the city.

Unlike previous Turkish incursions into Byzantine territory, Alp Arslan now annexed Ani to his empire. This was a signal for a tipping point, that the Turks would be a major rival and one who could and would take Byzantine land. Ironically, the loss of Ani to the Turks brought the voluntary surrender of the smaller Armenian kingdom of Kars, one of the few remaining Armenian states, by Gagik-Abas (r. 1029-1065 CE) to the Byzantine Empire. Gagik-Abas hoped the Byzantines would provide a better defense, and in exchange for his kingdom, he obtained safer estates in central Anatolia.

Meanwhile, there was a large Oghuz Turk (a separate group from the Seljuk Turks) raid in the Balkans. Although the large raiding party left as quickly as they had come, they had ravaged Bulgaria and Macedonia and had potentially reached as far as Greece itself. This demonstrated the growing ineptitude of Byzantine forces in face of new challenges. Around the same time, there was an uprising against imperial taxes in Greece led by Nikoloutzas Delphinas. This was ended through granting a general amnesty and Nikoloutzas was executed. The Byzantine Empire of Constantine was facing problems from every corner.

However, Byzantine reversals during Constantine's reign were most present in Italy. After the Norman victory over the Pope in 1053 CE, the Normans continued to seize towns in Byzantine Southern Italy. In 1057 CE, the brothers Robert Guiscard and Roger took control of Norman forces in Calabria, conquering the region over the next three years. Only Apulia, the side of Italy's boot closest to the Balkans, remained in Byzantine hands. In 1059 CE, the reformist Pope Nicholas II, looking for an ally against a rival antipope in Rome, turned a new page in the history of southern Italy by declaring Robert the Duke of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily. Of course, the Pope did not have the authority to give Apulia, still in Byzantine hands, to the Normans (nor Sicily for that matter, which was under Muslim rule), but the sense of legitimacy given to the Normans aided them against the Byzantines.

Italy had always been a low priority for the Byzantines, coming after their core provinces in the Balkans and Anatolia. Because of this, extra forces were not sent from Constantinople to help the governors of Byzantine cities in Apulia defeat the Normans. At best, the governors could just hope to resist Norman attacks. The Norman advance was slowed by internal dissension and an expedition to conquer Muslim Sicily. The Byzantines were alarmed when a Norman fleet was first launched against the Balkans in 1066 CE, but the Byzantine fleet destroyed it before it reached the Balkan shore. In 1068 CE, Robert Guiscard began the three-year siege of the Byzantine provincial capital of Apulia, Bari. When Bari was captured in 1071 CE, the Byzantine presence in Italy would be gone for the first time since the reign of Justinian (r. 527-565 CE).

Death & LEgacy

Unlike his immediate predecessors, Constantine tried to create a dynasty. He had three sons, the first emperor to have a son since Romanos II (r. 959-963 CE), and he was the first to try and establish a dynasty since the Paphlagonians, Michael IV (r. 1034-1041 CE) and Michael V (r. 1041-1042 CE). Constantine appointed his sons Michael and Constantine as co-emperors and his brother John as the high position of caesar. However, there was no established dynastic principle in the Byzantine Empire. While the Macedonian Dynasty (r. 867-1056 CE) enjoyed support as the rightful rulers in the eyes of the people, this was an exception stemming from the dynasty's longevity. The Doukas family would prove incapable of creating this same sense of imperial dynasty after the death of Constantine.

Constantine fell ill in October 1066 CE and was likely incapacitated until his death on 22 or 23 May 1067 CE. His sons were still children when he died, and so the succession would be untenable. Into the void would step Romanos IV Diogenes (r. 1068-1071 CE), a military commander, and the man would inherit the Byzantine Empire, including all the problems bred by Constantine's rule and international circumstances. Constantine's policies and the emergence of new powerful enemies set up the perfect storm that would culminate in the aftermath of Romanos' defeat by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 CE. After that, the Byzantine Empire's decline would accelerate, and the Byzantines would never be able to fully recover.