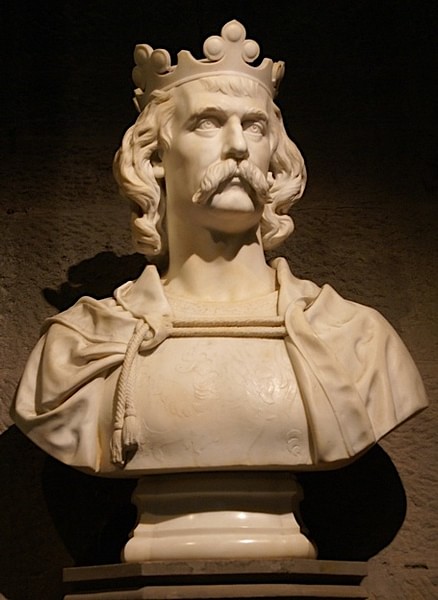

David II of Scotland ruled as king from 1329 to 1371 CE. Succeeding his father Robert the Bruce (r. 1306-1329 CE) when still a child, his early reign was threatened by the pretender Edward Balliol (c. 1283-1364 CE), son of King John Balliol (r. 1292-1296 CE). Edward Balliol had the support of Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377 CE), and he managed to declare himself king twice and rule parts of Scotland in Sep-Dec 1332 CE and again in 1333 to 1336 CE. David was forced into exile in France but returned to Scotland in 1341 CE. An invasion into northern England proved a disaster when David was captured at the Battle of Neville's Cross in 1346 CE and kept in the Tower of London for 11 years until a ransom secured his release. Ruling Scotland well when he got the opportunity, the king greatly improved the Crown's finances. David died without an heir in 1371 CE and was succeeded by Robert Stewart, the King's Lieutenant, who became Robert II of Scotland (r. 1371-1390 CE) and founder of the royal house of Stewart/Stuart.

Succession

David Bruce was born on 5 March 1324 CE in Dunfermline, his father being the king of Scotland Robert the Bruce, aka Robert I of Scotland. His mother was Elizabeth de Burgh (d. 1327 CE), the daughter of Richard de Burgh, earl of Ulster. Robert the Bruce had battled both Scottish rivals and English kings to gain and then keep his crown. When he died in June 1329 CE, his only male heir was David, then just five years old. David was crowned at Scone Abbey on 24 November 1331 CE; he was the first Scottish king to receive anointment as approved by the Papacy. David even had a small crown and a tiny sceptre made especially for him to hold during the ceremony. With a minor on the throne, an opportunity was presented for rivals to the Bruce family to try and take power. Protecting the king and leading a guardian council was Thomas Randolph, earl of Moray, and then, after his death in July 1332 CE, the Earl of Mar.

The Balliol Takeover

The chief rival to the Bruces was the Balliol family. This rivalry went back to the Great Cause of 1292 CE when Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307 CE) had chosen John Balliol to be the king of Scotland instead of Robert the Bruce (David II's great-grandfather). John had proved an ineffective king, and the Scots, instead, after a decade of infighting, finally rallied around Robert the Bruce (David II's father). However, the Balliols had never gone away, and now they saw their chance to reclaim the throne they considered rightfully theirs. The family figurehead was now Edward Balliol, the son of John Balliol. Edward had once been imprisoned in the Tower of London along with his father, but now he was back on centre stage, and crucially, he had the support of Edward III of England. The English king was eager to have his own man on the Scottish throne, even if his sister Joan (b. 1321 CE) had married David II on 12 June 1328 CE (an arrangement made when Edward had been a minor).

Edward Balliol had plenty of Scottish allies: the 'disinherited' - those barons disinherited by Robert the Bruce's parcelling out of lands to his own followers. As yet, Balliol still only had theoretical support from Edward III, but he, nevertheless, went ahead and invaded Scotland in August 1332 CE. Arriving by sea, the force defeated the royal Scottish army at Dupplin Moor near Perth on 11 August. David's guardian, Donald, earl of Mar, was killed in the battle. In September, Edward declared himself king, and he was crowned at Scone Abbey on the 24th. It was to be a short reign. In December 1332 CE, a victory by David's supporters at Annan ensured that Balliol was obliged to retreat to York. It was, though, a temporary respite to the musical thrones of 1330s CE Scotland.

Exile in France

In March 1333 CE Edward III sent a full English army to aid Balliol in laying siege to Berwick. The Scots responded with an army led by Sir Archibald Douglas. Balliol's combined army was still only half the size of Douglas', but the pretender won the engagement at Halidon Hill on 19 July 1333 CE thanks to a combination of archers and good use of topography. Thus, Edward was again crowned King of Scotland at Scone Abbey, but he struggled to win over the majority of the Scottish people who baulked at the plan to hand over parts of southern Scotland to England and become Edward III's vassal kingdom. Many, too, still regarded David as their lawful king, and the Bruce family still had the support of powerful barons and, most significantly of all, the King of France, Philip VI of France (r. 1328-1350 CE). The young ex-king and queen fled from Dumbarton Castle to the greater safety of France in May 1334 CE where they spent the next seven years. This court in exile was established at Château Gaillard in Normandy, which had been built by Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE). David was still a teenager, and here he studied books and learnt to use the knight's weapons of the medieval tournament. In 1339 CE, the young king even rode in battle (under his own banner) with the French army in Flanders.

The Fall of Edward Balliol

Back in Scotland and with many barons remaining loyal to the Bruce family, Edward Balliol's reign was partial in terms of territory and precarious indeed when he lost control of both Stirling and Edinburgh Castle. As rival barons clashed, Edward was deposed in 1334 CE, only to return in 1335 CE with a massive English army. David's allies avoided a direct confrontation with the invaders, which allowed Balliol to spend another precarious year on the throne.

David finally returned to Scotland in June 1341 CE. There he had to face competition from Robert Stewart, the son of Marjorie (b. c. 1295 CE), daughter of King Robert the Bruce and Isabel of Mar, and, therefore, David's nephew by marriage. Stewart had established himself as one of the foremost nobles in the kingdom during David's absence, and he, with the help of the guardian Sir Andrew Murray, had rid Scotland of Balliol in 1336 CE, who by then no longer enjoyed any practical support from Edward III. During the five years up to David's return, Stewart greatly enriched his own estates in the chaotic dealings with English/Balliol armies, a shift in traditional regional power bases, which would prove significant in the years to come.

The English-Scottish border was eventually re-established along traditional lines while from 1337 CE Edward III turned his attention to the richer prize of France and became preoccupied with what history has labelled the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453 CE). Scottish forces were able to repeatedly raid northern England, but France was insistent that Scotland honour its treaty agreements and do more to seriously damage its southern neighbour.

Relations with France

In the late-13th and 14th century CE, Scotland had been entertaining close ties with France, not coincidentally, England's number one enemy. In 1296 CE Scotland had formally allied itself with Philip IV of France (r. 1285-1314 CE), the first move in what became known as the 'Auld Alliance'. Then the 1326 CE Treaty of Corbeil formally established an alliance of mutual assistance between the two kingdoms. There was even a clause that should France attack England, then Scotland was also obliged to attack its southern neighbour.

In June 1340 CE the French king Philip VI assembled a fleet, probably intended to serve as a means to invade England, but it was sunk by an English fleet at Sluys in the Scheldt estuary (Low Countries). This was a fortunate escape for Scotland considering the obligations of the Treaty of Corbeil. The land battles of the Hundred Years' War which followed were all on French soil. However, Philip, in any case, called on his Scottish allies to invade northern England and force Edward to withdraw from France. David II, eager to get back lands Edward Balliol had given away to his English allies, obliged and invaded northern England in October 1346 CE.

Capture at Neville's Cross

Durham was the target of the Scots, but a numerically inferior English militia army led by, amongst others, the impressively named William la Zouche, Archbishop of York, defeated the Scots at the Battle of Neville's Cross outside the city on 17 October 1346 CE. Once again, English archers proved to be the great and decisive weapon of the moment. The Scottish cause was in no way enhanced by the desertion of certain leaders on the battlefield itself, notably Robert Stewart. Even more disastrous than the defeat, King David was injured by an arrow hitting his head and then captured along with over 50 Scottish knights. Six Scottish earls had died in the battle, too. The king was paraded in London before a jeering crowd on 2 January 1347 CE and taken to the Tower of London for a long but at least comfortable confinement.

Meanwhile, waging war was proving particularly easy for Edward III. Able to concentrate on continental affairs, the English gained a great victory at Poitiers in France in September 1356 CE. There, Edward's son, Edward, the Black Prince (1330-1376 CE), captured the new French king, John the Good, aka John II of France (r. 1350-1364 CE). Incredibly, Edward III now had two rival kings under lock and key.

During the king's forced absence, Scotland was ruled by Robert Stewart, now calling himself the King's Lieutenant. Stewart had no particular enthusiasm for raising the ransom necessary for the king's release. Besides dealing with cantankerous nobles and allowing general financial chaos in the kingdom, another complication to Stewart's tenure was the arrival of the Black Death in Britain in 1348 CE. Perhaps as much as a third of the population was killed by this terrible plague.

Return to Scotland

David was finally released on 7 October 1357 CE as part of the Treaty of Berwick, where the Scots agreed to pay a ransom and respect a 10-year truce between the two countries. The ransom for David's release was massive and had to be paid in instalments, and even then with difficulty. Over the years of the king's confinement, Robert Stewart and several Scottish parliaments had steadfastly refused to acknowledge King David's request to nominate the English royal family as the heirs of Scotland if he himself had no heir and so escape paying such an onerous ransom. Back on his throne again, David finally received formal submission from Robert Stewart in 1363 CE after the latter had tried and failed to depose the king.

And so a more stable Scotland was able to prosper. Instalments of the ransom still had to be paid but Edward III at least agreed to reduce them and to abandon his support for Edward Balliol (who, now in old age, renounced his claim and settled instead for a handsome pension). David used his powerful personality and judicious use of land grants and titles to gradually impose royal control over those barons who had become rather too powerful during his forced absence. The king, too, used his parliaments well to gather in more taxes, duties, and customs fees, which put the Crown in a significantly more secure financial position than it had been in decades.

Death & Successor

David died on 22 February 1371 CE in Edinburgh Castle, and he was buried at Holyrood Abbey. He left no heir, his wife Joan having permanently left for England back in 1358 CE after she had discovered the king with one of his many mistresses. A second marriage, this time to Margaret Drummond (d. 1375 CE) in April 1363 CE, ended in an annulment in 1369 CE, and no children were produced. David died before he could marry his proposed third wife, Agnus Dunbar. So, it was Robert Stewart who made himself king as Robert II of Scotland in 1371 CE after having bought off his chief rival Earl William Douglas. Thus was founded the royal house of Stewart (later to become Stuart) which would rule Scotland until 1714 CE.