Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446 CE) was an Italian Renaissance architect, goldsmith, and sculptor, who is most famous for his work on the cathedral of Florence and its impressive soaring brick dome, completed in 1436 CE. Considered one of the founding fathers of Renaissance architecture, Brunelleschi was particularly interested in the study of linear perspective and achieving a harmonious simplicity of form in buildings which also considered the immediate environment in which they were constructed.

Early Career

Filippo Brunelleschi was born in Florence in 1377 CE, the son of a successful notary. Like many other Renaissance artists, Brunelleschi studied surviving examples of classical sculpture and architecture in his home town, the region of Tuscany, and Rome. He trained first as a goldsmith and was an accomplished sculptor, but his concentration on architecture may be explained by his narrow defeat to Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE) in the competition for the (second set of) bronze doors of Florence's Baptistery in 1401 CE. Brunelleschi's trial panel for the competition survives and shows the story from the Old Testament of Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac. The panel, measuring around 53 x 44 cm, is now in the Bargello Museum of Florence. After the defeat, Brunelleschi returned to working gold as he joined the Florence guild of goldsmiths in 1404 CE. Art and architecture would, though, soon tempt him back out of his gloomy workshop and into the Renaissance limelight.

Brunelleschi's Architectural Vision

Brunelleschi took a great interest in the science of linear perspective, that is, creating the illusion of depth on a flat surface by having imaginary sightlines all converge towards a central point, a subject in which he was a pioneer. In the mid-1420s CE, he famously conducted experiments in perspective in public, notably on the entrance steps of Florence's cathedral using mirrors, a pinhole, and canvas. In two now lost paintings of Florence's Baptistery and urban landscape, the artist thus publicly demonstrated his ideas on linear perspective and his belief in the importance of identifying a single point of view within them. These ideas greatly influenced other Renaissance artists in both paintings and sculpture thanks to treatises then being written on the subject, which were spread around Italy and beyond. It was in architecture, though, that Brunelleschi was to prove his genius, and here, too, his ideas on perspective would cause contemporary and future architects to redefine how they viewed both architectural and urban spaces. Not only was it important what a building looked like, it now became important what it looked like in relation to its immediate environment.

Brunelleschi put all of these ideas into practice when he designed the influential Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence from 1419 to 1424 CE with its elegant loggia or gallery. The hospital was intended as a refuge for orphans and was funded by Brunelleschi's goldsmith guild. The loggia is an archetypal example of a Renaissance reworking of classical architectural elements, mixing in Tuscan Romanesque features and playing with precise mathematical proportions. Another successful project in Florence was the domed perfect cube of the Old Sacristy of the San Lorenzo Basilica (1418-28 CE). Indeed, the Sacristy was said to have been such a wonder, even when still not finished, that the crowds of admirers it attracted seriously annoyed the workmen there. The architect would go on to redesign the whole basilica from 1436 CE. Brunelleschi was sparing no expense for what was, in effect, the private church of the ruling family of the city: the Medici. Both of these buildings would hint at the masterpiece yet to come: Florence's cathedral dome.

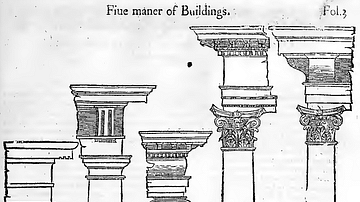

Brunelleschi's particular approach to technical aspects of architecture, as evidenced by these early buildings, is here summarised within the architect's entry in The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of the Italian Renaissance:

It is based on pure geometrical proportions, the use of sail vaults and saucer domes on pendentives, and a simple all'antica vocabulary of grey sandstone columns and pilasters articulating white plaster walls. His proportional systems are refinements of those used in medieval Florence, his orders and ornamentation are almost entirely based on Romanesque models…and specific Trecento models…Nonetheless, his synthesis is an entirely personal one, which far exceeds its component sources in intellectual rigour and control of design; the bichromatic combination of sandstone and plaster was certainly his own invention. (60)

Duomo of Florence

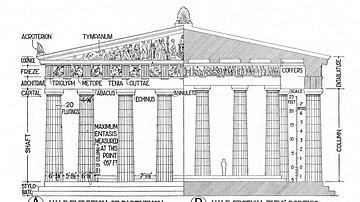

Work to finally finish off the Duomo of Florence, the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, began around 1420 CE after a competition had been held from 1418 CE to see who would have that particular honour. The cathedral had been founded in 1296 CE but its dome or cupola had never been completed, along with various other parts of the building. Such were the dimensions involved for any possible dome, most contemporary architects thought that building one here was a physical impossibility. Brunelleschi, who won the competition, believed otherwise. There was a catch, though. The Florentines wanted Brunelleschi to work with Lorenzo Ghiberti. Not best of friends since the Baptistery doors competition, it was said that Brunelleschi took several days off sick in the early stages of the project, simply to show up Ghiberti for the incompetent architect Brunelleschi thought he was. Ghiberti himself would claim half-credit for the finished dome but he had left the project before construction really got underway.

Besides being influenced by the structural methods used in ancient Roman architecture, Brunelleschi had studied examples of Byzantine churches with their multiple domes and particularly buildings in or influenced by Byzantine Ravenna and Venice. Romanesque features of Tuscan architecture and medieval proportions would be another influence. It is not known what the architect got up to between 1404 and 1415 CE, and it is quite possible he travelled more widely than traditionally assumed in his quest for existing answers to architectural problems. It is known that Brunelleschi was a student of mathematics and a keen engineer, and so he was uniquely armed with skills in both the arts and sciences, a true Renaissance man. To build his dome, Brunelleschi would need all these skills and more to turn an impressive plan into a soaring reality. Just to design and create a workable system of winches and pulleys needed for the construction work was a feat in itself. In addition, a detailed wooden model was needed for the workmen to follow, one of which survives today in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo of Florence. The team of builders was led by the master mason Battista d'Antonio.

The dome was a brilliant design and realised without a fixed centring (temporary wooden scaffolding) during the construction. Rather, each circular course of the dome was completed before another course was added on top. The dome is self-supporting thanks to the 8 outer and 16 inner ribs that rise from the base to the peak and which create self-supporting arches. As a consequence of this system, the dome has a pointed profile and is composed of eight distinct sides. Another consideration for the architect was that a pointed dome gives much less side thrust on the drum below it than a hemispherical one, thus eliminating the need for extra support for the drum such as might be given by unsightly flying buttresses. Made from bricks laid in a reinforcing herringbone pattern, the dome is given further strength and lightness by having a double shell.

The dome was completed in 1436 CE, making the cathedral the largest and tallest building in Europe at the time. The dome measures at the base 45.5 metres (149 ft.) in diameter - similar to Rome's Pantheon - and reaches a height of 91 metres (298 ft.). The lantern (which takes the form of a temple designed by Brunelleschi) and gilded sphere were added to the very top of the dome between 1445 and 1461 CE. The excessive weight of the lantern was necessary to keep the eight panels of the dome from springing outwards. Inside the dome, Brunelleschi originally had the ceiling painted white but it was covered with frescoes in the 16th century CE.

Everyone, from the Pope down to Brunelleschi himself, was both relieved and delighted with the finally finished cathedral. As the artist Leon Battista Alberti noted at the time, the "large structure, rising above the skies, ample to cover with its shadow all the Tuscan people" (Paoletti, 218) was a veritable marvel of human endeavour. It was felt, at last, that the Renaissance had now surpassed the engineering feats of antiquity.

Final Works

Brunelleschi's engineering skills were sometimes called on for far less noble projects than cathedrals, churches, and hospitals. One example was in 1430 CE when the Florentines attempted to flood the Tuscan town of Lucca into military and political submission. A huge low basin with surrounding dyke was created to gather water from the River Serchio but only ended in the unplanned disaster of flooding the Florentines' own camp.

On a smaller scale but still requiring ingenious feats of engineering, Brunelleschi was more successful with his mechanisms inside the San Lorenzo church of Florence. These machines were temporarily installed in the church when the Medici family wished to show off their largesse by entertaining the public with religious shows to commemorate important events in the Christian calendar. The effects created included a night of stars in the ceiling and the angel Gabriel descending in a shower of sparks.

One of Brunelleschi's last projects, begun in 1436 CE but actually completed long after his death, was the Church of Santo Spirito in Florence. With its elegant columns and arches, it is an excellent example of the master's preoccupation with simple yet harmonious design. Another unfinished project was the octagonal Santa Maria degli Angeli church. Brunelleschi had begun work on it in 1434 CE, and it shows his typical fondness for repeated identical features, which give the wall space a marvellous sense of rhythm.

Other posthumous works popped up elsewhere. Brunelleschi had adopted as a child a famous future artist, Andrea di Lazzaro Cavalcanti (1412-1462 CE), who would work on Florence's Santa Maria Novella cathedral after his adopted father's death. In 1434 CE Cavalcanti had run off with Brunelleschi's collection of jewels, but the pair were later reconciled. It was Cavalcanti who made the gilded marble pulpit for the cathedral (1443-48 CE), which was based on a wooden model made by Brunelleschi.

Reputation & Legacy

Brunelleschi is widely considered one of the pioneers and creators of what became known as a Renaissance architectural language. Classical proportions, simple geometry, and harmony were prime considerations in this new language, which replaced, or at least challenged, the hitherto dominance of medieval architecture. For example, Brunelleschi's use of tall slim columns to support arches which create a loggia with shallow domes (as best seen in his Ospedale degli Innocenti) was imitated for the facades of many other types of public buildings throughout the 15th century CE.

Linear perspective, as already noted, became a central theme and identifying feature of architecture, paintings, and sculpture thereafter. So then, just as the High Renaissance painters and sculptors like Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE), Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE), and Raphael (1483-1520 CE) created a new interpretation of classical themes in art, so, too, Brunelleschi revitalised architecture, especially in Florence, which was considered, in effect, the capital of the Renaissance movement.

Thanks to his works and a biography by fellow Florentine Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, Brunelleschi's fame spread to other Italian cities such as Milan and Urbino where a new generation of architects was about to appear, amongst whom was the great Donato Bramante (c. 1444-1514 CE), who would take on Brunelleschi's mantle as the greatest living Renaissance architect.