Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) was an English mariner, privateer and explorer who in 1588 CE helped defeat the Spanish Armada of Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE) which attempted to invade the kingdom of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE). Roaming the Atlantic and Caribbean capturing their treasure ships, the Spanish called Drake 'El Draque' ('the Dragon'). Partial to combining exploration with piracy, Drake famously circumnavigated the globe in his ship the Golden Hind between 1577 and 1580 CE. One of England's most celebrated seafarers and idolised in his own lifetime, Drake was witty but sly, generous yet cruel, both audacious and reckless, fiercely patriotic and almost always lucky - in short, the archetypal Elizabethan hero. He died of dysentery in 1596 CE on an expedition to raid the Spanish Main one last time.

Early Life

Francis Drake was born in Devonshire c. 1540 CE, his father was a modest landowner and chaplain in the Chatham dockyard. Aged ten, Francis was already sailing the Thames in a small bark, and in 1563 CE, he first went to sea proper. Three years later he joined his cousin John Hawkins on a trading voyage that visited West Africa, acquired a number of slaves and crossed the Atlantic to the New World. In 1567 CE Drake repeated the voyage, again with Hawkins, but this time he was captain of the Judith, a ship of a mere 50 tons. Unfortunately for the young mariner, this expedition was curtailed when it was attacked by the Spanish at San Juan D'Ulloa on the east coast of Mexico on 23 September 1568 CE. The new viceroy of the Spanish Empire, Don Martin Enriquez, had offered peace terms but then treacherously went back on his word, an infamous about-turn that the English would use as justification for privateering for the next 40 years.

At San Juan de Ulúa the English lost four ships but Hawkins and Drake survived to return to England in the two remaining vessels. This was the beginning of a very personal enmity between Drake and all things Spanish, a hatred that was fuelled by his militant Protestantism. From then on, Drake regarded it as a sacred duty to weaken Spain by any means possible. Often preaching on his ship and always carrying on board his copy of Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563 CE) on Protestants who had suffered under the reign of 'Bloody Mary', Drake would become the scourge of Catholic Spain and its Empire.

1572 CE: Panama & Privateering

On 24 May 1572 CE Drake sailed from Plymouth in the Swan, bound for Panama to explore what he could find there. Now that England and Spain were at war in all but name, Elizabeth, unable to fund large land armies on the Continent, considered that attacking Spanish treasure ships bringing loot from its New World empire was the best way to hurt Philip II of Spain and increase her own wealth. She was further motivated by Spain's continued exclusion of English merchants from trade with the New World. Accordingly, mariners like Drake were given a license to act as pirates and take whatever they came across of Spain's on the high seas. Courtiers, merchants, and sometimes even the queen herself, invested in these ventures, hoping to reap great rewards. The euphemistic name for the adventurers was 'privateers', the Spanish merely called them 'sea dogs'. Fitting out a fleet of ships and maintaining their crews was not cheap, though, and every expedition had to find its prize to make the whole thing financially viable. There was also the not insignificant matter that the Spanish did not take kindly to this nautical mugging and so their ships bristled with cannons.

1577-80 CE Voyage of Circumnavigation

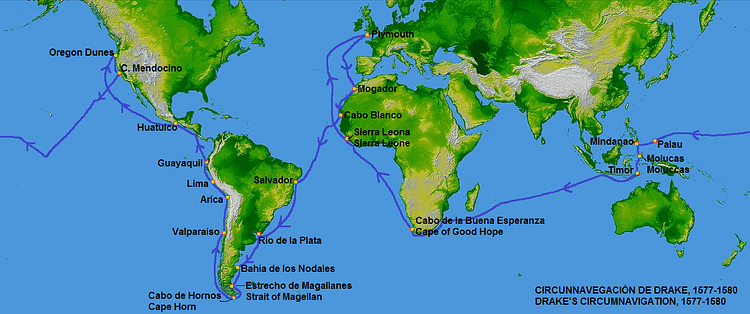

The idea to mount an expedition to explore what lay south of the equator and see if a great southern continent did really exist was first touted by Richard Grenville (1542-1591 CE) in 1574 CE. Grenville had failed to find backing for his plan as the search for the Northwest Passage took precedence, but in 1577 CE, Elizabeth turned to Drake for just such a southern voyage. Secretly, the queen invested in the project and instructed Drake not only to explore new trade possibilities but also to take whatever treasure he came across from the Spanish. Drake was given command of a fleet of five ships: Christopher, Elizabeth, Marigold, Pelican, and Swan. Mid-voyage the 140-ton Pelican would be renamed the Golden Hind in honour of Drake's principal patron, Sir Christopher Hatton, who had that device on his family coat of arms.

On 13 December 1577 CE Drake set off with 164 men on what would turn out to be an extraordinary voyage; 60 of the men would never see England again. The fleet sailed down the coast of northwest Africa and then across the Atlantic route to reach the eastern coast of South America in April 1578 CE. At the southern tip of South America, the Christopher and Swan turned back while the other ships pressed on through the Straits of Magellan in August. Heavy storms in September meant that the Golden Hind continued the expedition alone to sail up the west coast of South America. Spanish settlements like Valparaiso were taken completely by surprise when an English warship showed up in Pacific waters. Several treasure ships were captured, including in March 1579 CE the Nuestra Senora de la Concepćion (aka Cacafuego) off the coast of Peru with its massive cargo of silver.

On 4 April 1581 CE, Elizabeth boarded the Golden Hind docked at Deptford on the Thames and, pleased with the treasures he had captured and the glory of his navigational achievements, knighted Drake on its decks. This outraged the Spanish ambassador who regarded Drake as nothing more than a pirate. Drake had become Elizabeth's favourite sea dog, a feeling that must have been mutual as the mariner often gave his queen lavish gifts such as a gold crown embedded with emeralds and a diamond-studded cross in 1581 CE. The queen, too, gave gifts, notably a silver cup in the form of a globe which encased a coconut Drake had brought back from his voyage. Another present was the now-famous Armada Jewel by Nicholas Hilliard in 1588 CE, a gold and gem-encrusted brooch carrying two portraits of the queen. Drake, in terms of cash in his pocket, was probably then the richest man in England and he splashed out on a portfolio of properties which included Buckland Abbey. He acquired, too, a coat of arms (a ship atop a globe with two silver stars intersected by a wavy horizontal line or fess). His official motto became Sic Parvis Magna or 'Greatness from Small beginnings'.

1580s CE: More Privateering

In 1585 CE Drake sailed with a fleet of nearly 30 ships and 2,000 men to raid the Spanish West Indies. He freed many English ships that Philip had embargoed in Spanish-controlled ports that year and captured such a haul of Spanish arms it caused havoc with Philip's supplies meant for his Armada (see below). The important ports of San Domingo on Cuba and Cartagena, the capital of the Spanish Main, were sacked. The loot gained was not so great but Drake showed how vulnerable the Spanish Empire was to naval attacks. In the next couple of years, Drake roamed far and wide, making more raids on Spanish wealth in the Cape Verde islands, Colombia, Florida, and Hispaniola. Ships were captured and settlements torched as Elizabeth's number one 'sea dog' went to work on the Spanish Empire.

1587: The Raid on Cadiz

Philip's interest in England went back to 1553 CE when his father, King Charles V of Spain (r. 1516-1556 CE) arranged for him to marry Mary I of England (r. 1553-1558 CE). Mary's successor, Elizabeth I continued the Protestant English Reformation, and the Pope excommunicated the queen for heresy in February 1570 CE. Elizabeth was also active abroad, sending money and arms to the Huguenots in France and financial aid to Protestants in the Netherlands who were protesting against Philip's rule.

The already tense relationship between England and Spain was made worse by Elizabeth's privateers. Capturing ships on the high seas or attacking colonial settlements was one thing but when Drake went a big step further towards full-on warfare and attacked Cadiz in April 1587 CE, relations plummeted to a new low. Cadiz was Spain's most important Atlantic port and Drake 'singed the king's beard' in his audacious attack. Sailing straight into the harbour and ignoring the cannons fired from the fortress, Drake's fleet destroyed 31 ships, captured another six, and again destroyed valuable supplies destined for Spain's Armada. After three days, Drake sailed on to Cape Vincent in southern Portugal and spent another two months causing havoc among Spain's ships along the coast and as far out as the Azores. Philip's long-planned invasion, what he called the 'Enterprise of England', was delayed by these setbacks, but he remained determined to conquer his number one enemy. Philip even gained the blessing and financial aid of Pope Sixtus V (r. 1585-90 CE) as the king presented himself as the Sword of the Catholic Church.

1588 CE: The Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada, a fleet of 132 ships packed with 17,000 soldiers and 7,000 mariners, sailed from Lisbon (then under Philip's rule) on 30 May 1588 CE. It was intended that the Armada would establish dominance of the English Channel and then reach the Netherlands in order to pick up a second army led by the Duke of Parma, Philip's regent there. The fleet would then sail to invade England.

The Armada was commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia. England's fleet of around 130 ships was commanded by Lord Howard of Effingham with Drake as vice-admiral in his flagship the Revenge. The large Spanish galleons - designed for transportation, not warfare - were much less nimble than the smaller English ships which would, it was hoped, be able to dash in and out of the Spanish fleet and cause havoc. In addition, the 20 English royal galleons were better armed than the best of the Spanish ships and their guns could fire further.

The Spanish galleons were spotted off the coast of Cornwall on 19 July. Fire beacons spread the news along the coast and, on 20 July, the English fleet sailed from its homeport of Plymouth to meet the invaders. There were about 50 fighting ships on each side and there would be three separate engagements as the navies battled each other and storms. These battles, spread over the next week, were off Eddystone, Portland, and the Isle of Wight. The English ships could not take advantage of their greater manoeuvrability or the superior knowledge of tides of their commanders as the Spanish adopted their familiar disciplined line-abreast formation - a giant crescent. The English did manage to fire heavily at the wings of the Armada, 'plucking their feathers' as Lord Howard put it (Guy, 341). Although the English fleet outgunned the Spanish, both sides found themselves with insufficient ammunition, and commanders were obliged to be frugal with their volleys. The Spanish prudently retreated to a safe anchorage off Calais on 27 July having lost only two ships and suffered only superficial damage to many others.

Drake reported victory from Revenge:

God hath given us so good a day in forcing the enemy so far to leeward as I hope in God that the Prince of Parma and the Duke of Sidonia shall not shake hands these few days; and whensoever they shall meet, I believe neither of them will greatly rejoice of this day's service.

(Ferriby, 226)

The Armada was forced by the continuing storm to sail around the tempestuous shores of Scotland and Ireland in order to return home. A bad storm hit them in the Atlantic, and only half of the original Armada made it back to Spain in October 1588 CE. Philip did not give up despite the disaster of his great 'Enterprise', and he tried twice more to invade England (1596 and 1597 CE), but each time his fleet was repelled by storms.

1589 CE: The Portugal Expedition

An expedition was formed to attack both Philip's New World treasure ships and his remaining Armada ships in port in Spain in April 1589 CE. A mix of private and official ships and men, this expedition is sometimes called the Don Antonio Expedition as one of its leaders' aims was to capture Lisbon and restore Don Antonio to the Portuguese throne (he had been deposed by Philip in 1580 CE). Other names for this attack include the English Armada and the Drake-Norris Expedition, after Sir John Norris (c. 1547-1597 CE) who co-led the expedition with Drake. Elizabeth invested £49,000 pounds in the project but she would be sorely disappointed in the measly return.

The English fleet was impressive with 130-150 ships and at least 15,000 men. However, the expedition had confused aims and so, in the end, achieved little. Corunna was attacked but only partially captured and 2,000 Englishmen returned to England with their loot. Meanwhile, 50 Spanish ships idle in other Spanish ports were ignored. Lisbon was attacked - contrary to Elizabeth's instructions - but the Portuguese did not rise in support of Don Antonio as hoped for and the city resisted capture. Lacking sufficient supplies to continue and having missed the treasure ships coming through the Azores, the expedition retreated ignominiously back to England. With huge casualties, mostly from disease, the whole episode seriously damaged Drake's reputation and clearly showed that mixing private and state control of an expeditionary force only led to confusion and disunity. The queen was outraged with Drake at the attack on Lisbon, the complete failure to attack the Armada ships and the poor financial return. The old mariner thus became a landlubber and served as both the mayor of Plymouth and its Member of Parliament.

1595 CE: Final Expedition & Death

In August 1595 CE Drake showed the old sea dog still had some bite when he led an expedition alongside John Hawkins to the Caribbean. Men flocked to the docks at Plymouth, eager to sign up and sail with the greatest mariner England had so far produced. The objective of the 27-ship fleet was to attack the Isthmus of Panama where the Spanish silver caravans passed through. Alas, Hawkins died on the voyage out and then the attack on Porto Rico was a complete failure. The Spanish defences had been warned of the English fleet's arrival, giving them time to install extra cannons, and this intelligence also meant no treasure ships risked the area. Neither could any riches be found in the settlements Drake attacked. Beset with unfavourable winds as disease ran through the crews, Drake, then around 55 years of age, himself died of dysentery at Portobelo on 28 January 1596 CE. Sir Francis Drake was, fittingly, buried at sea in a lead coffin, but the Panama expedition was a damp squib of an end to a glittering maritime career.