The Grail Legend (also known as the Grail Quest, Quest for the Holy Grail) developed in Europe c. 1050-1485 CE. It most likely originated in Ireland as folklore before appearing in written form sometime before 1056 CE in The Prophetic Ecstasy of the Phantom, an Irish tale. The concept was popularized by the French poet Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190 CE) in his Perceval or the Story of the Grail (c. 1190 CE) which he left unfinished and was completed by other poets in the work known as the Four Continuations.

Chretien's story features a mystical castle, a grail (at this time a platter, not a cup), a strange procession, a woman who changes form, and a visiting hero who is expected to ask a question which will break a magic spell; all elements found in the earlier The Prophetic Ecstasy of the Phantom. Chretien's grail was transformed into the cup of Christ at the last supper by Robert de Boron (12th century CE) in his Joseph of Arimathea and later writers would continue this tradition. The grail's association with Christ's cup was standardized by Sir Thomas Malory in his Le Morte D'Arthur (1469 CE), which is how it is best known in the modern day.

The grail legend may have developed from Celtic shamanic rituals in which an initiate was required to pass certain tests to attain an elevated visionary state. The quest for the grail, then, would be a quest for the meaning of life, the nature of the divine, and symbolize one's true purpose in living. The resonant nature of the tales of the quest has inspired audiences for centuries, and the Arthurian Legends remain as popular in the present day as they were in the past.

Early Origin

Scholar Jessie L. Weston, in her seminal work From Ritual to Romance, claims that the grail legend developed from early oriental fertility rites which linked the health of a monarch to that of the land. The monarch was kept healthy, or cured of whatever ailed him, through this ritual which involved pageantry and role-playing. This concept traveled via trade to Europe where it came to be expressed in folk tales which would then develop into medieval literature.

Arthurian scholar R.S. Loomis cites the first known written version of a 'grail story' as The Prophetic Ecstasy of the Phantom, written in Ireland sometime before 1056 CE, possibly c. 1050 CE even though this tale does not mention a grail per se. In this story, the High King of Ireland, Conn, meets a phantom horseman who turns out to be the fertility god Lugh. Lugh invites Conn to dine at his palace, and they set off together, but when Conn arrives at the palace, he finds Lugh already there and a great feast prepared. While Conn sits, he is served enormous portions of meat and drink by a pretty crowned maiden known as The Sovranty of Ireland. When she brings a golden chalice of ale to the feast, she asks Lugh, “To whom shall this cup be given?” and Lugh answers, “Pour it for Conn.” As Conn drinks from the chalice, Lugh falls into a trance and gives the names of all Conn's royal descendants. Lugh and his palace then vanish, and Conn is left alone with the chalice.

This is the sort of tale Weston discusses as having arisen from fertility rituals. The early rituals would have somehow involved a figure representing the king and others symbolizing natural forces which supported and encouraged the king's reign. Conn in the story represents the monarchy but not the concept of sovereignty which is clearly symbolized by the crowned maiden. When the maiden asks the fertility god who should be given the honor of the chalice, he indicates Conn – the king is being honored by the natural world and the monarchy is willingly served by natural sovereignty which is the acquiescence of the land and people to a given monarch. Lugh then assures the king of a long, unbroken line of descendants – of continued fertility – and, the message delivered, the supernatural beings and their palace disappear, leaving Conn with a potent souvenir of the encounter.

Chretien's Perceval

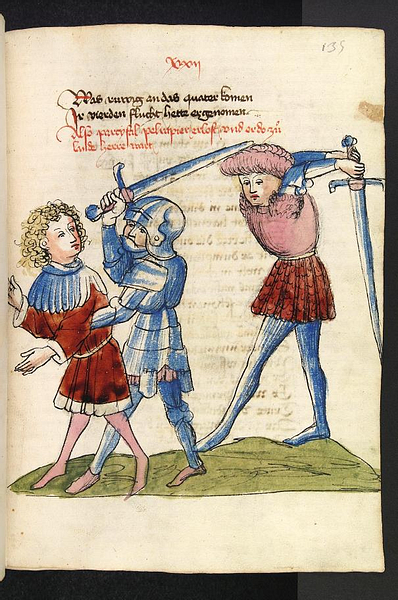

According to Loomis, this Irish tale is a precursor to Chretien's 1190 CE poem Perceval or the Story of the Grail which is the first appearance of the Grail by name in world literature. At one point in this poem, the knight Perceval of King Arthur's court meets the Fisher King (also known as the Grail King) who invites him to dine at his castle. As in the earlier tale, the Fisher King arrives at the castle before Perceval and a great feast is laid. Perceval witnesses a strange procession as he eats: a bleeding lance, a candelabra, and a grail are carried past him and into an adjoining room.

When Perceval was being trained as a knight, his instructor impressed upon him the importance of not showing one's mind by holding one's tongue and that a knight should never be overly talkative; therefore, even though he wants to ask what the procession means, he remains silent. He wakes up the next morning to find the Fisher King, the servants, and the castle gone, and he is left alone to saddle his horse and continue on his travels. He later meets a woman weeping who scolds him for not asking whom the grail served because, if he had, he could have healed the king and the land.

The grail in Chretien's work is a platter and Arthurian scholar Norris J. Lacy explains how a contemporary audience would have known this:

The word itself is not shrouded in mystery. It is one of the numerous reflexes of medieval Latin gradale, a word that meant “by degree”, “in stages”, applied to a dish or platter that was brought to the table at various stages or servings during a meal. (257)

In Chretien, Perceval should have asked, “What is the grail? Whom does it serve?” and by asking these questions a connection would be made between the injured and ailing king, his infertile land, and the power of the grail to heal and restore. Chretien died before he could finish the poem but other poets carried the tale to conclusion in the Four Continuations, with Perceval redeeming himself for his earlier lapse, succeeding the Fisher King as monarch, and ruling justly over fertile and bounteous land.

Robert de Boron & Wolfram von Eschenbach

Chretien's works were popular reading and highly influential, even his unfinished Perceval, and inspired the poet Robert de Boron to write his own romance, Joseph of Arimathea, in which the Grail is transformed from a pagan symbol of fertility and healing to the cup Jesus Christ drank from at the Last Supper. Joseph of Arimathea is mentioned in all four biblical gospels as a secret disciple of Jesus Christ who donated his time and tomb following the crucifixion. In medieval folklore, he came to Britain after Christ's resurrection carrying the Grail, the cup Christ drank from at the Last Supper, which Joseph used to catch Christ's blood in when he was on the cross, and he founded an abbey at Glastonbury.

Robert de Boron picks up on this lore in his poem in which Joseph hides the Grail in his house following Christ's execution and is imprisoned shortly afterwards for his Christian faith. Christ appears to Joseph in prison, gives him the Grail which had been hidden, and teaches him the secrets of its use. The Grail's magic prevents Joseph from aging and keeps him in perfect health until he is released from prison many years later and sails for Britain.

Robert Christianized the earlier pagan motifs of the Arthurian Legends and also introduced the famous symbol of the Sword in the Stone (a different weapon than Arthur's sword Excalibur) which establishes Arthur as the true king of Britain but presents it as a sword in an anvil (which would become a stone only later). Two other writers working at about this same time, Beroul and Thomas of Britain, contributed further to the development of the legends – Thomas reintroducing the elements of courtly love established by Chretien – but the Grail legend would next be developed by the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach (c. 1170-c. 1220 CE) in his Parzival.

Wolfram's Parzival is considered the greatest German epic of its age (and would later empower the works of Wagner). Inspired by Chretien's Perceval (although Wolfram in his text not only denies this but mocks Chretien), the Parzival is a tale of spiritual awakening, a Bildungsroman (story detailing a character's education, journey to maturity, spiritual quest), in which Parzival travels from a state of chaos and self-doubt to one of self-acceptance, grace, and peace.

Book V of the Parzival has the hero leave Arthur's court and arrive at the Castle of the Grail whose lord, Anfortas, suffers from a wound that will not heal. Parzival does not ask about the wound nor about the strange procession which passes before him, and for the same reason that Perceval remained silent in Chretien's work. The next morning, he wakes to find the castle and all its inhabitants gone and blames the experience on evil spirits trying to confuse him. In Wolfram's tale, the Grail is not a platter or a cup but a stone – a kind of jewel – which provides the choicest foods one could wish for in abundance. Knowing that no such thing could exist, Parzival dismisses the entire episode. Upon arriving back at Arthur's court, the lady Sigune angrily tells him he should have asked Anfortas the meaning of the procession and the grail but does not tell him why.

Parzival embarks on a quest to find the grail, is tutored by a holy man in its meaning and value, and finally engages in single combat with a knight who, symbolically, turns out to be himself. He is defeated by this knight who breaks his sword but then makes peace with him and leads him to an understanding and acceptance of himself. In the end, Parzival becomes the Grail King just as he does in the French Four Continuations of Chretien's poem.

The Vulgate & Post-Vulgate

The Grail legend was further developed in Wales in the Mabinogion (c. 1200 CE, though the stories are probably older) which presents the grail as a cauldron which provides whatever one wants to eat or drink in abundance. The grail then again becomes a chalice in the work of the monk Layamon (late 12th/early 13th century CE) whose Brut is the first version of the Arthurian Legend in English. Layamon's Brut is the primary source for the first prose version of the legend in English, the Vulgate Cycle (also known as the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, 1215-1235 CE). This is the first time the legends appear in prose, and this is significant because prose was reserved for serious non-fiction (theology, history, philosophy), while works of the imagination were always rendered in poetry. The fact that some unknown scribe would take the time to write the story in prose suggests how seriously the subject matter was taken at this time.

One very interesting aspect of the development of the Arthurian Legend and the Grail Quest is the silence of the medieval Church. There is no condemnation or criticism of the Arthurian romances even though they flagrantly challenged the Church's teachings on marriage, fidelity, or one's purpose in life from c. 1056-1215 CE. By the time the Vulgate Cycle was written, the legends had been largely Christianized but, still, it would seem the medieval Church would have come out with some statement regarding the courtly love genre and the Arthurian Legends.

According to some scholars, most notably Denis de Rougemont, the Church did act on this through the Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229 CE) which crushed a heretical sect known as the Cathars. According to this theory, the courtly love romances were religious allegories symbolically representing Cathar beliefs. The Cathars believed the Church was corrupt, did not represent the divine truth, and that the Bible was mostly authored by Satan. They rejected the resurrection of Jesus Christ as any kind of historical reality, claiming the gospel accounts were a symbolic representation, and they believed in a goddess Sophia (wisdom) whom the church had unjustly abducted from the true believers (Cathars = Pure Ones, the true faithful).

According to this theory, the damsel in distress who must be rescued by the knight is Sophia, her abductor is the Church, and the knight is the true Cathar devotee. The grail, as first depicted by Chretien, would be the key to the knowledge of the truth of the divine; one only had to ask the question of who the grail served to become enlightened. The failure of the various knights to ask this question was due to their indoctrination into the false teachings of the Church.

Le Morte D'Arthur

This claim, like Jessie L. Weston's that the medieval romance arose from pagan ritual, has been repeatedly challenged by scholars and is by no means universally accepted. By the late 15th century CE, the Arthurian Legends were mostly Christianized and, through the Vulgate Cycle and its revised version known as the Post-Vulgate Cycle, came into the hands of Sir Thomas Malory, a knight well-read in Arthurian romance, who was a political prisoner of Newgate prison in London.

Malory gathered the various versions of the Arthurian Legend, working primarily from the Post-Vulgate Cycle, to create his masterpiece Le Morte D'Arthur which tells the story of the rise and fall of King Arthur, his noble knights, and his court of Camelot. Malory tells the tale of Arthur's birth, tutelage by Merlin the wizard, and ascent to power by drawing the sword from the stone. Arthur then receives his sword Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake, marries his queen Guinevere (who brings him his Round Table), and embarks on a reign of reform and justice in which his knights help the poor and oppressed instead of exploiting and punishing them. Arthur's initiatives change his kingdom and the surrounding regions for the better until the affair of his best friend and greatest knight, Sir Lancelot, with Guinevere is discovered and the entire court falls to pieces.

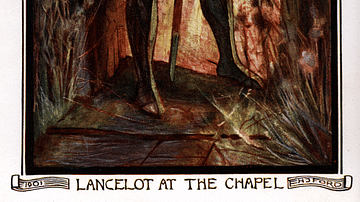

Prior to this, however, in Tale Six of Malory's work, the Holy Grail appears in Arthur's court and a voice commands the knights to find it. Lancelot is the best bet for bringing the Grail back to court but this is only because no one yet knows of his affair with Guinevere. Lancelot's secret sin prevents him from completing the Quest for the Grail, which is finally concluded by his illegitimate son of the lady Elaine of Corbenic, Sir Galahad, the pure in heart.

Conclusion

Malory's work, published in 1485 CE by William Caxton, was a bestseller but fell out of favor during the Renaissance when the reading public was more interested in classical literature. It was revived by the British poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in 1859 CE through his Idylls of the King and, since then, the Arthurian Legend has continued to exert considerable influence on literature, art, and culture.

In the 20th century CE, it formed the basis of the highly influential poem The Wasteland by T. S. Eliot (1922 CE), which then informed the literature of the writers of the so-called Lost Generation, most notably Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises (1926 CE) in which the protagonist, Jake Barnes, is both the Fisher King and the knight who must bring healing to the wasteland of western culture in the aftermath of WWI. James Joyce, Ezra Pound, William Faulkner, and many other notable authors drew on the Grail legend in their works, and scholars in the present day continue to mine the stories for existential and spiritual significance.

Weston's assertion that the Arthurian romances originated in pagan fertility rituals has been challenged, as noted, but her claim continues to exert considerable influence. Scholar Dan Merkur, in his 1999 CE work The Mystery of Manna, notes the similarities of experience between the pilgrim-knight on the Grail Quest and shamanistic experiences which closely parallel Weston's claims. As in the earliest account of The Prophetic Ecstasy of the Phantom, through Chretien's work, Wolfram's, and the rest, in the shamanic experience the initiate comes to an unknown place where there is the potential for transformation, but that initiate must know what to ask and what to humbly receive in order to attain higher knowledge of the self and the world. The Grail legend continues to resonate with a modern audience because it illustrates the underlying motivation of the human condition: the quest to find ultimate meaning and purpose in life.