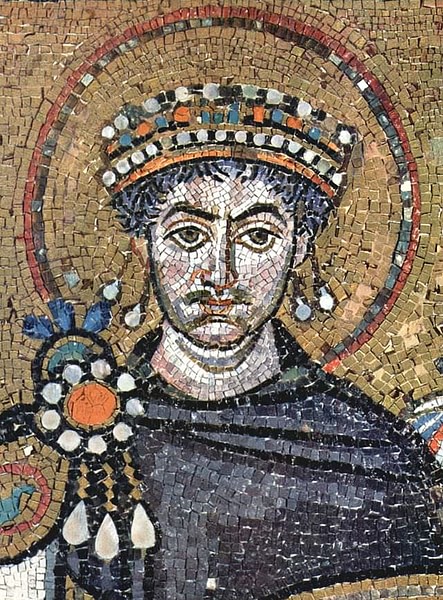

Justinian I reigned as emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 527 to 565 CE. Born around 482 CE in Tauresium, a village in Illyria, his uncle Emperor Justin I was an imperial bodyguard who reached the throne on the death of Anastasius in 518 CE. Justinian is considered one of the most important late Roman and Byzantine emperors. He started a significant military campaign to retake Africa from the Vandals (in 533 to 534 CE) and Italy from the Goths (535 to 554 CE). He also ordered the rebuilding of the Hagia Sophia church (begun in 532 CE) as well as an empire-wide construction drive, resulting in new churches, monasteries, forts, water reservoirs, and bridges. His other great achievement was the completion of the legal reforms encapsulated in the Corpus Juris Civilis between 529 and 534 CE. This was the bringing together of all the Roman laws that had been issued from the time of Emperor Hadrian (117 - 138 CE) to the present. He is widely held as one of the greatest (and most controversial) late Roman/Byzantine emperors in history.

Justinian's Early Life

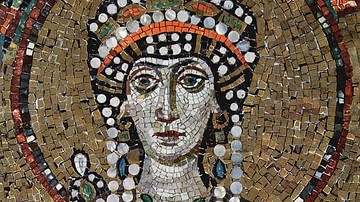

Not a great deal is known about Justinian's early life. His mother Vigilantia was the sister of the Excubitor (Imperial bodyguard). Justin adopted his nephew and brought him to Constantinople to guarantee his education. During Justin's reign, Justinian acted as a close confidant and advisor; he became Consul in 521 CE and thereafter commander of the Eastern army. In 525 CE he married Theodora, a woman from a poor background and possibly a courtesan.

Though not an active soldier himself, Justinian initiated an enormous military enterprise with the aim of taking Italy, Sicily, and Africa. His military career began, however, in the east. The Iberian War (526 - 532 CE) was fought against the Sassanian Empire over control of the kingdom of Iberia in the Caucasus mountains (roughly the modern state of Georgia). The conflict was one theatre of a wider war against the Sassanian Empire going back to the time of Anastasius I. After several battles, a truce was signed upon the death of the Sassanian Shah (emperor) Kavadh I and the accession of his son Khosroes I.

Justinian & the Vandals

The Vandals had been in control of Africa's capital Carthage since 439 CE and thereafter spread their influence over Africa, Tripolitania, Corsica, Sardinia, and the Balearic islands. In 533 CE Justinian launched a reconquest effort aimed at claiming these areas for the Byzantine Empire. This began in the spring of 533 CE with an anti-Vandal revolt in Tripolitania (today's western Libya), which was consolidated by Roman soldiers from the empire's province of Cyrenaica. Soon after, General Belisarius (Justinian's most successful military leader) led a force of soldiers in ships from the Aegean, stopping off at Sicily and landing in Africa. A series of battles followed, and in the winter of 534 CE, the Vandal king Gelimer surrendered, leaving Africa in Roman hands after almost a century of Vandal rule.

The Gothic War & Totila

The Goths had been in control of Italy and Sicily since 476 CE, when the last Roman Emperor in the West, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed. Though the Gothic Rex Italiae (King of Italy) Odoacer recognised the authority of the emperor in Constantinople, the Gothic regime began to initiate policies independent of the Roman sphere. The Roman aristocracy of Italy remained in a position of privilege even after the Gothic conquest, but conflict and disagreement emerged in 524 CE with the execution of the leading Roman Italian politician Boethius. In this context of discontent in the Gothic regime, Justinian sought to retake Italy and Sicily. The rapid conquest of Africa had encouraged the emperor, and he sent Belisarius with a small force to attack Sicily, which fell quickly to the Romans in 535 CE. By 540 CE, after a series of victories and defeats against the Goths and their allies in Italy as well as in Dalmatia (modern Croatia), Italy was secured for the Romans.

However, this was not the end of the Gothic War. Though much of Italy was under Roman control, some towns and cities (such as Verona) remained under Gothic influence. Though soundly defeated, the remainder of the Gothic regime found a new leader in Totila. In the autumn of 541 CE, he was proclaimed king, soon after leading a reconquest of Italy. Though at the head of a relatively small force, Totila was helped in his goals by several problems in the Roman Empire. Around the same time, new hostilities opened between Justinian and the Sassanian Empire, which meant that resources had to be split between East and West. An outbreak of plague in 542 CE (later called the Justinianic Plague) crippled the empire's ability to respond. Totila thus managed to defeat the first Roman counter-attacks and captured Naples by siege in 543 CE. Rome itself changed hands three times in quick succession, ending up in 549 CE in the hands of Totila. Belisarius had attempted to defeat Totila on several occasions prior to this but was hampered by lack of supplies and support from Justinian. A new campaign was undertaken by Justinian's nephew Germanus Justinus, but he died in 551 CE, succeeded by the general Narses. In 553 CE, Narses defeated Totila and Italy was once again Roman.

Justinian's reign lasted almost 40 years, but it was not always popular. In 529 CE Julianus ben Sabar, a messianic figure in Palestine, led a revolt of the Samaritan people against the empire. In 532 CE Constantinople was gripped by civil discontent; the Nika riots lasted a week, resulted in the deaths of thousands of citizens, and left much of the monumental centre of the city in ruins. A second Samaritan revolt in 559 CE, more significant and possibly involving elements of the Jewish population of Palestine, was not quelled until after the death of Justinian.

The Codex Justinianus

Early on in his reign, Justinian commissioned a legal expert in his court, Tribonian, to gather together numerous legal notes, commentaries, and laws of the Roman legal system into a single text which would hold the force of law: this was the Codex Iustinianus. In 529 CE the first edition was published, followed in 534 CE by a revised second edition (which unlike the first, survives today). The text is divided into titles relating to specific aspects of the law, and was composed in Latin. It contained laws on heresy, orthodoxy and paganism as well.

Justinian's Life by Procopius

Justinian is unique among Roman emperors in that his life was recorded in two separate sources by the same author. Procopius of Caesarea, who was a legal secretary to General Belisarius, composed De Bellis ("On the Wars [of Justinian]") between 545 and 553 CE, which records the successes and some failures of the military campaign the emperor launched. He also composed De Aedificiis ("On the buildings [of Justinian]") between 550 and 557 CE, a work describing in great detail the many building projects the emperor undertook during his reign. Procopius also composed the Anecdota (translated as "Secret History", less often as "Unpublished Things") between 550 and 562 CE that claims to reveal the reality of life in the imperial court. It details the alleged sexual activities of the Empress Theodora, the weak determination of the emperor, and the power that women held in the imperial court. Considering the very negative tone of the text, it is unclear if Procopius intended the work to portray a satirical take on life at court or a truer account of imperial life than is portrayed in the De Bellis or De Aedificiis. What is almost certain is that the Anecdota reveals that Procopius had lost faith in the regime of Justinian, in contrast to the positive feelings expressed in his earlier works.

Justinian is credited as one of the greatest emperors in late Roman and Byzantine history. His achievements in the fields of art, architecture, legal reform, and conquest are remarkable by the standards of any leader in history. The works of Procopius have contributed greatly to this understanding as well as criticisms of his regime. His Christian faith was evident in all the spheres of his enterprise, marking a step in the transition of emperors from leaders in war and politics to leaders of faith and patronage as well.