The Kingdom of West Francia (843-987 CE, also known as The Kingdom of the West Franks) was the region of Western Europe that formed the western part of the Carolingian Empire of Charlemagne (Holy Roman Emperor 800-814 CE) known as Francia or the Kingdom of the Franks.

The region was once part of the land known as Gaul and when the Roman Empire fell during the 5th century CE, was taken largely by the Visigoths (although other peoples also claimed land). These various ethnic groups and principalities were conquered by the Salian Frank king Childeric I (r.c. 458-481 CE) who continued the policies of his father Merovech, founder of the Merovingian Dynasty (450-751 CE). The Carolingian Empire (800-888 CE) came to power after a long period of unrest, civil war, and invasions and again united the land under the reign of Charlemagne and his successors until 843 CE when it was divided into West Francia (later France) and East Francia (later Germany) with Middle Francia eventually becoming the Alsace-Lorraine region.

West Francia is featured significantly in the TV series Vikings which follows the adventures of the legendary Viking raider and king Ragnar Lothbrok. The Vikings launched a number of raids on the region throughout the 9th century CE, laying siege to Paris twice, until the Frankish king Charles the Simple (r. 893-923 CE) negotiated with the Viking leader Rollo (r. 911-927 CE) for peace and protection in exchange for land. West Francia would prosper under succeeding kings up through the rise of the Capetian Dynasty, whose founder hailed from Ile-de-France, establishing the Kingdom of France in the region in 987 CE.

Early History & Division

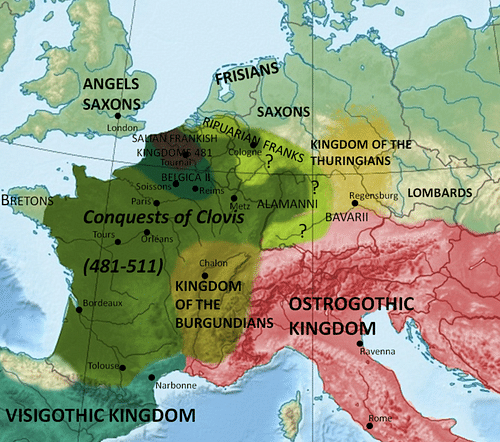

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, the region known as Gaul was governed by separate kingdoms of the Visigoths, Alemani, and others until its conquest by the Salian Franks under Merovech and Childeric I who founded the Merovingian Dynasty. Childeric I's son, Clovis I (c.466-511 CE), would unite the land under his reign to become the first King of the Franks, ruling from c. 509-511 CE, and the region appears in documents at this time under the name Francia.

After Clovis I's death, his kingdom was divided between his four sons, reunited under the reign of Clothar I (r. 511-588 CE), and then again divided into the three territories of Austrasia, Burgundy, and Neustria. Although ruled by kings, the actual power in government was the position known as Mayor of the Palace (roughly equivalent to a Prime Minister) whose occupant made all the actual decisions and formed policy while the king appeared in public ceremonies and performed necessary rituals.

The most powerful of these mayors was Pepin of Herstal (c. 635-714 CE) who defeated his opponents in battle in 687 CE and proclaimed himself Duke and Prince of the Franks, reigning 687-714 CE. His son and successor was Charles Martel (r. 718-741 CE) famous for his victory over the invading Muslim armies at the Battle of Tours in 732 CE. Charles' victory secured the borders of Francia and the stability of his reign encouraged overall prosperity which was continued by his successor Pepin the Short (r. 751-768 CE), founder of the Carolingian Dynasty and father of Charlemagne.

Charlemagne ruled as King of the Franks between 768-814 CE, at first with his brother Carloman I until Carloman's death in 771 CE, winning numerous military victories and conquering opponents of the church until he was powerful enough to be proclaimed Holy Roman Emperor in 800 CE and found the Carolingian Empire (800-888 CE). He was succeeded by his son Louis I (Louis the Pious, (814-840 CE) who reformed the empire and emphasized the common bond all his subjects shared in the Christian faith.

Louis I succeeded, to a great degree, in creating a homogeneous empire united in faith and vision but this would not last. Upon his death, his sons plunged the region into civil war in a power struggle over who would succeed him. For three years the brothers led their armies against each other until peace was finally established by the Treaty of Verdun in 843 CE. The former empire of Charlemagne and Louis I was divided between the brothers with Louis the German (r.843-876 CE) taking East Francia, Lothair I (r. 843-855 CE) controlling Middle Francia, and Charles the Bald (r. 843-877 CE) ruling West Francia.

West Francia & Viking Raids

Throughout Charlemagne's reign, he engaged in almost incessant warfare to expand his own power and that of the church. His Saxon Wars (772-804 CE), carried out to subjugate the region and convert the Norse pagans to Christianity, destroyed the land and resulted in thousands of deaths, most notably in the Massacre of Verden in 782 CE when Charlemagne ordered the execution of 4,500 Saxons. As many of these Saxons had relatives in Denmark, this outrage was not soon forgotten and the history of West Francia would be significantly impacted by Viking raids primarily from Denmark.

The Franks and the Scandinavians were known to each other long before Charlemagne through trade and had been on good terms. Scholar Janet L. Nelson cites a number of examples of cordial relationships including one in which a Frankish bishop, lost in northern Frisia, was helped by “Northmen”, most likely Danes (Sawyer, 20). The expansion of Frankish power under Charlemagne no doubt worried his neighbors but it is not until the Saxon Wars that there is any evidence of actual conflict.

The leader of the Saxon resistance, Widukind, sought help from Sigfried of the Danes who allowed Saxon refugees into his kingdom and protected them. In 798 CE, Charlemagne demanded that this policy stop and Sigfried complied but, when Saxony was finally conquered in 804 CE, the Danish king Godfred reacted and arrived with a fleet of ships and a large army. He ravaged Frisia, part of Charlemagne's realm at this time, and imposed tribute on the region. Charlemagne was mounting an expedition against him to win back these lands when Godfred died and his successor sued for peace.

Even so, the precedent had been set for swift Norse retaliation against Frankish aggression. Nelson notes how Godfred's military strike against Frisia would be mirrored by later Viking raiders and, further, how the Vikings were continually so successful:

Godfred had seriously threatened Frankish control of Saxony and the alliances that underpinned it. He possessed cavalry; he could muster a very large fleet; he understood the value of merchants and tolls and was capable of transplanting an entire trading center onto his own territory; he could undertake public works, mobilizing teams under his subordinates to carry them out; he could plausibly challenge the Franks to pitched battle. (21)

After Charlemagne's death in 814 CE, other Scandinavian raiders remembered Godfred's success. Attracted by the wealth of the Franks, and with no Charlemagne to fear any longer, they began making incursions up the River Seine to raid Frankish settlements. The first Viking raid was in 820 CE but the raiders had no idea of what kind of force they might be facing, the numbers, or the terrain and so were easily defeated and driven off. When the Vikings returned later, however, they were much better prepared. In 841 CE, the Viking leader Asgeir sacked and burned Rouen and much of the surrounding countryside, carrying off substantial loot; other raiders would soon follow his example.

Vikings raided West Francia throughout the reign of Charles the Bald. The Norse chieftain Reginherus (one of the possible inspirations for the Ragnar Lothbrok character) lay siege to Paris in 845 CE and, when all attempts to end the siege failed, Charles paid the Viking chief to leave. Asgeir returned to raid the region in 851-852 CE and others between 854-858 CE. The famous Bjorn Ironside, claimed to be the son of Ragnar Lothbrok, raided the region alongside the notorious Hastein (also known as Hasting) in c. 858 CE and by 860 CE Charles the Bald had employed a Viking Chieftain named Veland to rid the land of other Viking raiders who, by this time, were too numerous for the Franks to manage.

In 876 CE the Vikings ravaged and burned the region around Rouen and, after Charles' death, came back again to besiege Paris in 885-886 CE; two raids thought to have been led – or at least participated in – by the Viking chief Rollo. All of these raids destabilized the region and the people lived in a near-constant state of fear of Viking attacks which came with little or no warning and devastated the countryside.

The Counts of West Francia & King Odo

Aside from the Viking skills mentioned above by Nelson, what encouraged the success of the Viking raids was the structure of West Francia following the death of Louis I and the division of the empire. Even though the treaty had been struck, there was still tension between the three brothers and this would only worsen later with their successors. Further, although Lothair I, Louis the German, and Charles the Bald ruled their respective regions overall, the distinct principalities within those regions were controlled by counts who held significant power and autonomy. The policies of these counts, naturally, sought to increase their own power at the expense of their neighbors. As scholar Henri Pirenne points out:

Their most evident interest was to defend and protect the lands and the people who had become their lands and their people. They did not fail in a task which a purely selfish concern for personal power had imposed upon them. As their power grew and was consolidated, they became more and more preoccupied with giving their principalities an organization capable of guaranteeing public order and peace. (50)

This peace and order, however, usually was only apparent in the immediate vicinity of their courts and laws were often poorly enforced elsewhere in their districts. Further, the focus on their own lands discouraged any inclination to help those elsewhere. When the Viking raids began, therefore, individual regional defense was mounted wherever they struck but help from neighbors could not be counted on.

Among the best examples of the power of a count is Odo of Paris who would reign as king of West Francia 888-898 CE. During the period of civil unrest in which the successors of the brothers warred with each other and the Vikings harried the region, Charles the Bald and his sons successively died. At this same time, a man later known as Robert the Strong (c. 830-866 CE), Count of Anjou, grew in power and wealth through military campaigns and defense of his realm. He was killed in a Viking raid in 866 CE, leaving behind his family including the eldest son Odo.

When the last of Charles the Bald's successors had died without an heir, the people of West Francia invited Charles the Fat of East Francia (Louis the German's youngest son) to take control in 884 CE. Between the time of the death of Robert the Strong and the advent of Charles the Fat, Odo of Anjou had grown up to become as powerful a count as his father.

When the Vikings attacked Paris in 885 CE, it was Odo who mounted a defense of the city and held off the siege. Charles the Fat, who had no taste for battle of any kind, arrived to relieve the city in 886 CE but, instead of engaging the Vikings in battle, paid them to leave and directed them to go raid in Burgundy instead. The people then advocated for Odo as king of West Francia and Charles the Fat was deposed in 888 CE.

Odo was able to successfully defend Paris owing to his personal characteristics, of course, but also the power he held as count of his district. Even so, he was not a legitimate heir to Charles the Bald and so the nobility of West Francia suggested he step down in favor of Charles the Simple, grandson of Charles the Bald. Odo resisted their various pressures until he was finally persuaded to concede but died before he could abdicate. As he had no heirs, Charles the Simple succeeded to the throne of West Francia without challenge in 898 CE.

Charles the Simple & Rollo of Normandy

The Viking raids by this time had been going on for nearly a century and Charles needed them to stop. The Viking chief Rollo had been in the country since the Paris siege of 885-886 CE conducting successful raids from his camp on the Seine between 887-911 CE. Although Rollo certainly destroyed property and crops, and no doubt killed a number of people along the way, he seemed primarily interested in loot and slaves, not murder or destruction just for the sake of it.

Nelson notes how events like Rollo's raids demonstrate the “Northmen's clear desire to capture rather than to kill” (Sawyer, 29). Captives could be sold and the Vikings grew rich from the slave trade. Clearly it was more profitable to carry monks away from their abbeys and people from their farms than to kill them and the records of the time suggest this is what Rollo did.

When Charles found he could not stop Rollo in any way, he fell back on the precedent of paying a Viking chief to leave or, as in the case of Veland (and others) to stay but fight for West Francia instead of plundering it. He proposed an offer of land to Rollo, along with marriage to his daughter Gisla, if the Viking would become his Christian vassal. Rollo accepted and the Treaty of Saint Clair sur Epte was signed in 911 CE.

The lands Rollo was given became Normandy and he remained true to his word, protecting West Francia from further Viking raids and improving every aspect of his region. He reformed the laws and encouraged trade and agriculture as well as campaigning with Charles the Simple to restore order in other regions. The reign of Charles the Simple and Rollo of Normandy mark the first prolonged time of peace and order since West Francia was established in 843 CE.

Charles' rule was challenged by Robert I (r. 922-923 CE), Odo's younger brother and himself a powerful count, over a dispute concerning rights and titles in the Kingdom of Lotharingia, formerly of Middle Francia, and conflict broke out. Rollo fought for Charles at the Battle of Soissons in 923 CE in which Robert I was killed but his army won. Charles was captured and Rollo retreated to Normandy. Robert I was succeeded by Rudolph, Count of Burgundy and Troyes, who married Robert's daughter Emma of France and took the crown as Rudolph of France (r. 923-936 CE). Charles the Simple remained in captivity until his death in 929 CE and Rollo retired from leadership in 927 CE, dying in c. 930 CE of natural causes, most likely in his capital at Rouen.

Charles the Simple and Rollo of Normandy had stabilized West Francia to allow for actual growth and development of the region. Although there would be further hostilities and military conflicts during the reign of Louis IV (r. 936-954 CE), the great king Lothair (r. 954-986 CE), who united the region, Louis V (r. 966-987 CE) culminating in the rise of Hugh Capet (r. 987-996 CE), founder of the Capetian Dynasty and the Kingdom of France.

West Francia in Vikings & Legacy

West Francia is featured in the TV series Vikings beginning in Season 3. As the show is entertainment, not history, it is not expected to adhere to the historical record and makes free use of poetic license. In the actual 845 CE raid by Reginherus, the people of Paris had fled before the Vikings arrived and there was little if any actual combat; more Vikings died of dysentery in the raid than in battle. The dramatic scene in Season 3:10 in which Ragnar converts to Christianity, seemingly dies, and then leaps from his coffin once inside the cathedral is taken from an account of the Viking leader Hastein who is said to have used this trick at least twice in other cities, not Paris.

Gisela of France was only a young girl at the time of her betrothal to the historical Rollo in 911 CE and so her depiction in the show is completely fictional. The depiction of Odo, Count of Paris, is accurate only in so far of his defense of the city and personal power but not in his interactions with Therese in Season 4. Methods used in defense of the city are accurate to the 9th century CE.

The 845 CE siege by Reginherus is conflated with the 885-886 siege of Rollo in both seasons 3 and 4. In neither case is there any record of the Vikings dismantling their ships and hauling them overland to attack Paris from another vantage point; although there is evidence that Vikings did this in the Shetlands and in Russia (among other places) and the depiction in the show of how it was done is accurate. Scholars have concluded that Viking ships could be hauled overland long distances using the methods shown in the TV series and that this was done for a number of reasons including waters that were hard to navigate or the need to get from one body of water to another quickly.

Whatever license is taken by the show for entertainment purposes, the producers succeed in telling the story of Viking influence in West Francia and how Rollo of Normandy helped to stabilize the region. The Norse and the Franks assimilated following the cessation of the Viking raids to create a unified culture and ethnicity. Nelson writes:

Women provide one test of cultural compatibility. Was the occupant of an allegedly `Viking' grave found near Pitres a Viking or a Frank? All we can say is that she wore jewelry of a `Viking' style. She may have been a Dane who embraced Christianity. She may have been a Frank who had embraced a Dane. [In the records of the time] there is no mention of rape, and this is significant, given that these annals twice mention episodes when the followers of Christian Carolingian kings committed rape. (Sawyer, 47)

The Norse who had come as raiders remained as citizens, adopted the language and culture, and added to it from their own. They converted to the Christian faith of the land and fought for it with the same zeal they had previously shown as pagans. The contributions of the Vikings to West Francia are numerous and touch upon every aspect of the region which, following the rise of Hugh Capet, would become the country of France.