Gaius Musonius Rufus (c. 30 CE - c. 101 CE) was an influential 1st-century CE Stoic philosopher. While in modern times he is best known for being the teacher of Epictetus (c. 50 CE - c. 130 CE), Rufus was a highly respected figure in ancient times, considered by Origen a 'Roman Socrates' and by Tacitus as the foremost Stoic of his day. His life was an example of Stoic apathetic resistance to corrupt leadership and to the vicissitudes of time.

Throughout his life he was exiled three times; exile being a terrible punishment for a Roman citizen, seen at times as even worse than death. His relative lack of recognition in modern times is probably due to the unfortunately meagre remains we have from his teachings. Nevertheless, some lectures and fragments were preserved by his students.

Life

Existing sources make it difficult to establish a full biography, but it is clear that like other Stoics of his time, he had a very interesting life. He was born before 30 CE in Volsinii (modern Bolsena) to an Etruscan family of the equestrian class and died sometime before 101 CE.

When the senator and Stoic Rubellius Plautus was exiled from Rome in 60 CE by Emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE), Rufus joined him to his estate in Asia. When Nero declared open season on Plautus, Rufus counselled him, against the advice of his friends, to await death calmly rather than to flee and live in fear. Rufus' advice may seem hard to us, but it is in line with the Stoic teaching that death is not something to be terrified of and that the most important thing is to live according to one's conscience, as a reflection of the logos, or reason. Rufus's advice was accepted by Plautus, and he was indeed executed in his home by a freedman shortly after.

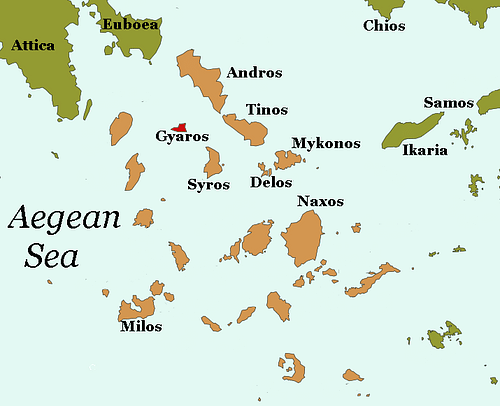

It is in his second exile, however, that Rufus is revealed not just as a theoretician but as a real practitioner of the Stoic art of living. Annoyed by his popularity, Nero exiled him to Gyaros, an arid and unpopulated island in the northern Cyclades, the 'Alcatraz' of Roman times, which even the earlier emperor Tiberius (14-37 CE) - who was not known for his compassion - considered as too cruel of a punishment for being "harsh and devoid of human culture" (Tacitus, Annals, 3.68-69). Nevertheless, Rufus was able to transform his exile into an opportunity. He personally uncovered a source of fresh water and began working the soil together with students who joined him in exile. Groups of students travelled to listen and work with him, and Gyaros became an unlikely centre of philosophy.

In his lectures, Rufus denies exile is necessarily negative. He introduces farming as an ideal occupation to practice and teach philosophy. He invites the aspiring philosopher once again to look within and to remember that the ultimate purpose of the Stoic practitioner is to develop one's virtues:

Certainly the person who is exiled is not prevented from possessing courage and justice simply because he is banished, nor is he denied self-control or any virtue that brings honour and benefit to the man with a good reputation and worthy of praise. ... If you are good, you will never be harmed or degraded by exile, for your virtues will help you and sustain you. But if you are bad, it is the evil that harms you and not exile, and the misery you feel in exile is the product of evil, not of exile. (Discourse 9)

In 70 CE, Rufus was banished for the third time, to Syria, this time under Vespasian's rule (r. 69-79 CE). Before being banished, however, he managed to prosecute and arrange the execution of one Ignatius Celer, a treasonous so-called philosopher, who wrongfully informed on one of Rufus' friends to Nero. We know very little of his later life and death.

Musonius Rufus & Epictetus

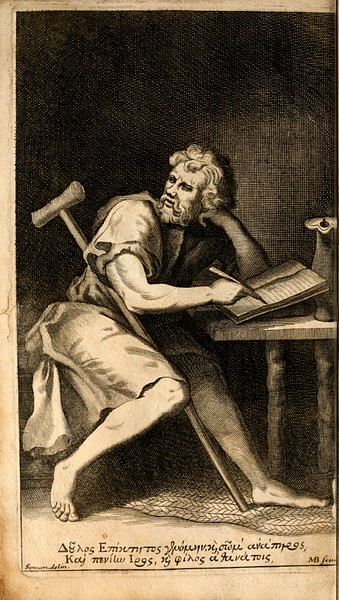

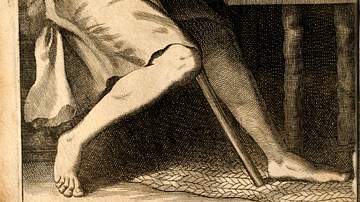

Rufus is primarily known today as the teacher of Epictetus, the slave who became a famous Stoic teacher. Epictetus received permission to go study with Rufus, and we may assume that his teachings were at least partly inspired by him. Epictetus later founded his own philosophy school in Nicopolis (in today's west Greece).

Epictetus mentions Rufus several times in his discourses. In one case, he mentions that Rufus tended to try and discourage his students in order to see who really has a good natural disposition. According to Epictetus Rufus used to say "like a stone, if you cast it upward, will be brought down to the earth by its own nature, so the man whose mind is naturally good, the more you repel him, the more he turns toward that to which he is naturally inclined." (Discourses, Book 3, Chapter 6).

Based on Epictetus' examples and anecdotes, and assuming that he himself adopted some teaching techniques from his Stoic master, we can deduce that Musonius' teachings were transmitted through formal lectures on different topics, discussions, Socratic dialogues, logic exercises, reading and interpretation, and recitation.

Teachings

Stoicism was a philosophy in the classical style, which meant it was not just an intellectual discipline, but a way of life. One did not just think as a Stoic, but one lived as a Stoic. It was a method or a system of living, a very pragmatic one as such and very useful in allowing its practitioner to withstand the trials of living with more dignity and forbearance.

Now in very truth, philosophy is training in the nobility of character, and nothing else. (Discourse 4)

By the time of Musonius, Stoicism was already a 300-year-old philosophy school imported to Rome from Athens a hundred years earlier and popularized in Rome by philosophers like Panaetius and politicians like Cicero. Rufus is considered a pioneer of the Late Stoa, epitomized later by Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius.

According to the remains we have of his teachings, it seems Rufus' main focus was the philosophical branch of ethics. He taught philosophy in order for his students to know what is truly good and to practice it in their lives. Philosophy was not an intellectual exercise, but a discipline to be trained and developed. The goal was not material success, but virtue. Rufus also did not disconnect one's individual life from one's social life. According to Rufus, to be a good person is to be a good citizen - one's virtue is found in the way we fulfil our responsibilities in life and in the way we treat our fellow citizens.

Laurenti (1989 CE) and Dillon (2004 CE) divide the practice of philosophy according to Musonius into three parts:

- Discernment - to discern between what is truly good and truly bad, and our false impressions of good and bad.

- Integration - to make this practice of discernment a second nature, so it can be evoked at any moment necessary.

- Practice - to use this practice in order to make the right decisions by not avoiding those things that are only apparent evils, as well as not pursuing these things that are only apparent goods. While at the same time pursuing the true goods and avoiding the true evils.

These elements clearly appear later in the teachings of his student, Epictetus.

In his teachings, Musonius emphasizes the practicality of Stoicism for the various aspects of everyday life, and in the fragments left to us, we find him talking about anything from marriage and childbirth and education to the question of obeying one's parents and food as a spiritual exercise.

In the question of marriage, he is quite a conservative, justifying sexual relations only for the sake of childbirth, yet he does not see any obstacle in marriage or rearing children for the practice of philosophy. This is in accord with the idea that Stoicism is not meant for books, but for the challenges of real life. He also does not see any reason why women should not receive the same education as men, both having the potential and the need to be virtuous.

Works

We do not know whether Musonius wrote anything for publication. Unfortunately for us, very little of his teachings remain. In the 5th-century CE anthology of Stobaeus we find 21 of his discourses, allegedly put down by one Lucius, a disciple of Musonius. We also have some fragments: a collection of sayings and anecdotes mentioned by other later philosophers.

Legacy

While we know that Musonius' influence as a philosopher lasted at least until the 3rd century CE, his most enduring legacy for us is the imprint he left on his disciple, Epictetus. In a way, this reminds us of another famous teacher-disciple relationship in the history of philosophy, that of Socrates and Plato. In both cases, we have no choice but to deduct the nature of the unknown "father", through the "son".

This leads us to believe that Musonius Rufus aimed to be an example of philosophy as a way of life. This concept, which was brought back to light by French philosopher Pierre Hadot in the 20th century CE, views philosophy not as an elaborate, intellectual, labyrinthine discipline, but as a methodical path to bring the mind and passions to heel and to use reason to make out a virtuous way of life in the midst of difficulties. This pursuit makes Musonius relevant today as he was almost 2,000 years ago.