The Norman Conquest of England (1066-71) was led by William the Conqueror who defeated King Harold II at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The Anglo-Saxon elite lost power as William redistributed land to his fellow Normans. Crowned William I of England (r. 1066-1087) on Christmas Day, the new order would take five years to fully control England.

Following Harold’s death at Hastings, William was obliged to see off several major invasions and rebellions, but once established, Norman England would witness profound changes in all areas of society. These changes included a restructuring of the Church, innovations in military and religious architecture, the evolution of the English language, the spread of feudalism and a much greater contact with continental Europe, especially France.

The Claims On the English Crown

In 1066 when the Norman invasion began, the king of England was Harold II, formerly Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex. Harold had hardly had time to warm his throne, crowned as he was on 6 January 1066 but it would soon prove to be one of the most hotly contested thrones in medieval Europe. Two other men considered themselves the rightful king of England, and both were highly dangerous and experienced military leaders.

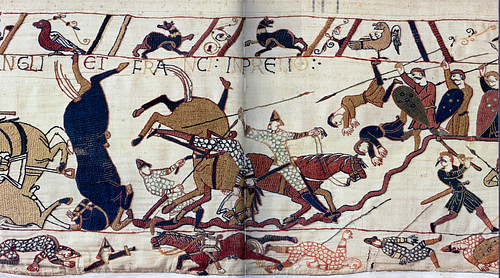

William, Duke of Normandy (r. from 1035), centred his claim on his relationship with Harold's predecessor, Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066) who was a distant relation (Count Richard I of Normandy was Edward's grandfather and William's great-grandfather). William also claimed that the English king, without children of his own, had once promised the Norman he would be Edward's successor. As it turned out, on his deathbed Edward selected the Anglo-Saxon Harold, a member of the enormously powerful Godwine family and then the foremost military commander in England, as the official heir. The Normans also claimed that Harold had visited Normandy in 1064, where he had been captured by the Count Guy of Ponthieu and then handed over to William. A condition of Harold's release, so the Norman version of the story goes (and additionally captured in the Bayeux Tapestry), was that the Earl of Wessex promised to become William's vassal and prepare the way for an invasion. Thus, William felt wronged and was fully prepared to enforce his claim with a full-scale military invasion of England.

Such was the scale of William's preparations in the summer of 1066, Harold knew full well what was coming and he gathered an army to await the Norman's dreaded arrival. Unfortunately for Harold, time passed without the invaders turning up and he was forced to stand down his army. Even worse, the third claimant to the English throne then chose his moment to enter the complex political drama.

Harald Hardrada was the king of Norway (aka Harold III, r. 1046-1066) and he had two dubious points to his claim: first, he believed he was also the rightful ruler of Denmark, a kingdom which had long-claimed sovereignty over large parts of England and, second, his predecessor, Sweyn (Swein) of Norway had been the illegitimate son of Aelfgifu, wife of King Cnut (aka Canute), the king of England from 1016 to 1035. Like William, Hardrada was prepared to press his claim through force, and he amassed an invasion fleet which sailed to England in September 1066. Harold faced the impossible situation of two invasions in the opposite parts of his kingdom at exactly the same time; at the very least, 1066 was going to be very eventful indeed.

Battle of Hastings

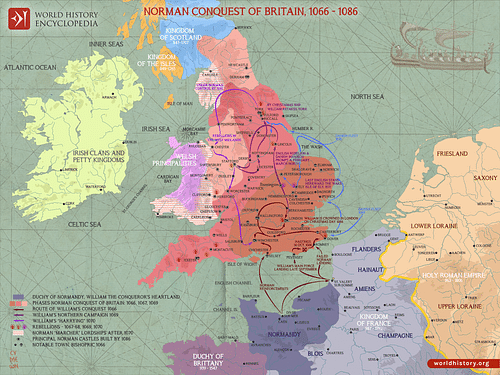

Hardrada's invasion was initially successful against an Anglo-Saxon army, led by two inexperienced English earls, at the Battle of Fulford Gate near York on 20 September. Then Harold marched a second army northwards and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, also near York, five days later, in which Hardrada was killed along with his ally, Harold's traitorous brother Tostig. Next, on 28 September, William and his invasion army landed at Pevensey in Sussex, southern England. Harold had little option but to march back to the south and do battle for a second time, speed being of the essence as the Normans had already begun torching pockets of south-east England.

Harold arrived in London on 6 October and mustered what forces he could, a mixture of the army from Stamford Bridge and a local levy (fyrd) of less well-trained troops from the shires. The two armies, likely numbering around 5,000 men each, faced off at Hastings on 14 October. The Anglo-Saxon army was largely composed of infantry, with the elite being the king's housecarls (huscarls) who wore chain armour and wielded huge axes. The Normans and their French allies, in contrast, had a significant number of archers, probably a unit of crossbowmen, and at least 1,000 cavalry.

Initially, when Harold occupied a small rise known as 'hammer-head ridge', the English resisted well the early Norman attacks, thanks to their strategy of protecting each other with their shields. When discipline broke amongst the Anglo-Saxons, though, and warriors moved down the hill in pursuit of a (perhaps feigned) Norman cavalry retreat, the battle swung in William's favour. Eventually, the cavalry was successful in breaking up the Anglo-Saxon 'shield-wall' formation and, when Harold and his two brothers were killed, William's victory was assured. The English king, at least according to tradition, was felled by an arrow to his eye, and then he was hacked to pieces as he lay prone on the ground. It was a great victory for William, who rested his men and then prepared to continue his invasion by subduing the south-east of England and taking London.

William's March on London

The great city of London was one of William's priorities but it was protected both by the River Thames from the south and by the fact the only crossing point was an easily defended fortified bridge. Consequently, the Norman duke decided on a much less direct attack. In effect, William performed a gigantic loop around south-east England and so was ultimately in a position to cut off the roads leading to London and attack the city from the north in November 1066. En route, reinforcements landed from Normandy and the important towns and fortifications of Romney, Dover, Winchester, and Canterbury were all taken. In the event, William's successes elsewhere and the lack of a significant army after the loss at Hastings saw the remaining Anglo-Saxon nobles and their figurehead Edgar Ætheling, great-nephew of Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066), surrender the city and the kingdom without a fight.

The victorious Norman duke was crowned William I of England on Christmas Day 1066 in Westminster Abbey, bringing an end to 500 years of Anglo-Saxon rule. Motte and bailey castles were built everywhere, and Norman lords took over estates across the conquered territory. William now sought to focus on the northern half England and subdue the lingering Anglo-Saxon rebels there, which included Eadwine, the earl of Mercia, and Morcar, the earl of Northumbria (both of whom had deserted London in its hour of need). 1066 had been spectacularly successful for the Normans but William now faced five years of on-off fighting to fully secure all the parts of his kingdom.

Rebellions, Invasions & the Harrying of the North

In the summer of 1067 the first of a long line of threats appeared on the horizon. This first danger came from an unusual quarter, too, in the form of Eustace of Boulogne, one of William's former allies, who attacked Dover with a fleet from northern France. Just after this attack was repelled, another threat came at Exeter where a major rebellion had broken out, largely motivated by William's new burdensome taxes. The king marched there personally and lay siege to the city for 18 days until it capitulated in January 1068. By the spring, William felt secure enough to invite his wife Mathilda over from Normandy and have her crowned the queen of England in Westminster Abbey on 11 May.

Far from being over, though, a new danger came in the form of Godwine, son of Harold II, then in self-imposed exile in Ireland. Godwine assembled a fleet of rebels and pirates and landed on the western coast of England at Avonmouth in the summer of 1068. Bristol was the target, but the city resisted, and a local shire army was mustered, which successfully saw off the attack and forced Godwine to return to Ireland.

At the same time as this failed Godwinson fightback, a rebellion broke out in York. The key city of the north, and indeed the entire region, had always been difficult to rule by kings based far to the south. William again responded emphatically, marching northwards, all the time razing any rebellious villages and towns he came across and building castles, notably at Warwick and Nottingham. The rebels at York were rallying around their figurehead of Edgar Ætheling who had been benefitting from both the sanctuary and active support of the king of the Scots, Malcolm III (r. 1058-1093) who had married Edgar's sister Margaret. The rebels wanted the lands back which many had lost since Hastings, and they wanted Edgar as their king. Fortunately for William, his army had been so ruthless during its march northwards that by the time the Normans arrived at York, the city decided it was better to surrender. William had a castle built, a garrison installed and hostages were taken, all to ensure the city did not forget who the rightful king was.

The peace did not last long, and in January 1069, both Durham and York were sacked by rebel armies. Once again, William marched north and this time routed the rebels in battle. Not able to rest on his laurels, a few months later William faced yet another foreign threat, this time in the guise of King Sweyn II of Denmark (r. 1047-1076). Sweyn sent his brother, Asbjorn and 300 ships to attack the northeast coast of England to see what they could plunder from the unsettled kingdom. There these Viking warriors teamed up with Anglo-Saxon rebels and sacked York. For a third time, William marched north to the city, but by the time he got there the rebels had fled and the Danes had sailed off down the River Trent. In age-old fashion, the king paid the Vikings to go home, and as a clear statement of his intent to rule the whole of England, William spent Christmas 1069 at York.

The Ely Rebellion & Completion of the Conquest

King Sweyn of Denmark arrived in person on English shores in 1070. The force led by his brother the previous year had never left England as they had promised William to do but the harsh winter and lack of foraging possibilities had depleted their numbers significantly. Otherwise, Sweyn may have planned to launch a full-scale invasion of England. Instead, the Danes linked up with Anglo-Saxon rebels who had been gathering under the local noble Hereward the Wake in East Anglia. Hereward had lost his family's lands following the conquest, and these allies of mutual mischief attacked Peterborough in the summer of 1070, looting the monastery there. Unfortunately for Hereward, the Danes then sailed off home with this treasure and left him alone to face William's wrath. Despite the setback, the rebel leader continued his guerrilla warfare with some success, and he gradually attracted more followers from across the country, including Earl Morcar.

After several small expeditions failed to break through the difficult terrain of the fens of East Anglia, William was obliged to lead an army there in person. Methodical as ever, in the summer of 1071 the king mobilised by both land and sea, eventually building a causeway which allowed him to transport the siege engines with which he could attack Ely Abbey, now the rebel headquarters. After fortifications were built around the abbey and seeing William's determination at close quarters, the rebels either surrendered or fled. William had put down the last Anglo-Saxon rebellion to threaten his reign. Then, in 1072, Scotland was attacked to stop the regular raids on Northumbria, and when Malcolm III sued for peace, part of the deal saw Edgar Ætheling exiled to Flanders. A new chapter of English history was already underway: the Normans were here to stay.

Impact of the Conquest

Besides the terrible deaths, widespread destruction, and appearance of castles everywhere, there were many other consequences to the Norman conquest in England and abroad. The most immediate impact was seen in the almost total replacement of the Anglo-Saxon ruling and landowning elite by a much smaller number of Normans, all given estates and titles by William. This dramatic changeover of ownership is starkly revealed in William's 1086-7 Domesday Book. A knock-on effect of this policy was the further development of the system of feudalism, that is the giving of lands (fiefs) to a lord (vassal) who promised his king military service (either in person or by paying knights or both). With this policy, the system of manorialism also evolved to become much more widespread. That is free and unfree (serf or villein) labour was used to work the land for the owner's profit.

The Church elite did not escape notice either, with almost all bishops being replaced by Norman ones, diocese headquarters were often moved to urban centres, and new stone cathedrals in the Norman-Romanesque style of architecture were built such as at Winchester, York, and Canterbury.

Although there was no great population movement from Normandy to England, ordinary people would have witnessed first hand this changeover of the elite, even if some Anglo-Saxon tools of governance like sheriffs did continue (although the offices themselves went to Normans). French was heard everywhere, and the language had a lasting influence on English syntax and vocabulary. Finally, as Norman lords, like William himself, often kept their own lands back home, the politics, economics, and cultures of the two countries became intertwined with sometimes drastic consequences in the coming centuries. England was already developing under the Anglo-Saxons into a powerful European kingdom but the Norman invasion certainly accelerated that process and so made England both the dominant country in the British Isles and one of the major players in the affairs of continental Europe thereafter.