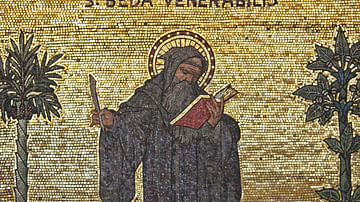

Oswald of Northumbria (c. 604 - c. 642 CE) was a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon king and saint. He came to power in Northumbria c. 633 or 634 CE following his victory over Cadwallon ap Cadfan, King of Gwynedd. Oswald ruled over the Northumbrian kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira but also exerted significant authority over parts of modern-day England, Wales, and Scotland. Oswald's reign is praised by the Northumbrian historian Bede, writing in the 8th century CE; he is one of the heroes of Bede's influential work, the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People). Oswald vigorously spread Christianity in his kingdom and beyond. C. 642 CE, he was killed at the Battle of Maserfield against the Mercian king Penda. Following his death, Oswald was revered as a saint and martyr. His relics were venerated and a cult formed in England and on the Continent which thrived in the Middle Ages.

Background, Early Life, & Exile

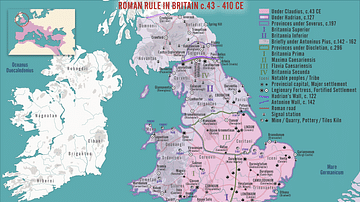

During Oswald's life, the term Northumbria was not yet in use. The region that would later generations call Northumbria was then roughly composed of two separate kingdoms, Deira and Bernicia, which lay north of the River Humber. The term Northumbria probably came into use in the early 8th century CE to describe the lands north of the Humber. The kingdom of Deira extended roughly from the Humber River north to the Tees River. Bernicia lay to the north of Deira and stretched from the Tees River to the Firth of Forth. The royal houses of the two respective kingdoms were often referred to as Angles in the ancient sources, as opposed to Saxons who seem to have ruled many of the kingdoms to the south. The two families were enemies, constantly at war with each other from the end of the 6th century CE through much of the 7th century CE.

Oswald was one of seven known children of Aethelfrith of Bernicia and Acha, with his birth generally dated to c. 604 CE. His older brother Eanfrith seems to have been Aethelfrith's child from another union. Very little is known about these children other than Eanfrith, Oswald, and Oswiu. In 604 Aethelfrith became king of Deira as well as Bernicia, probably through conquest. He married Acha, sister of Edwin of Deira and daughter of the deposed king, uniting the two rival kingdoms under his own rule. Edwin himself fled south to escape Aethelfrith. For some years, Edwin wandered in exile while Aethelfrith designed to have him killed. Eventually, Edwin was welcomed at the court of Raedwald of East Anglia. Raedwald refused Aethelfrith's request to have Edwin killed, instead, he turned on Aethelfrith, defeating and killing him in battle near the River Idle c. 616 CE.

Aethelfrith's death forced his sons to flee north into exile as Edwin had done years earlier. Oswald spent his exile in the Gaelic kingdom of Dal Riata, which covered much of western Scotland and part of Ireland. During his exile, Oswald converted to Christianity though his father had been a pagan.

Battle of Heavenfield & Kingship

In October 633 CE, Edwin met the combined armies of Penda of Mercia and Cadwallon of Gwynedd at the Battle of Hatfield Chase. The battle was a resounding defeat for Edwin's forces; Edwin was killed and much of his army destroyed. The kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia, united under Edwin's rule, were once again split between the two respective royal houses. Oswald's brother Eanfrith returned from exile to rule Bernicia while Edwin's cousin Osric ruled Deira. Penda seems to have returned to Mercia, but Cadwallon continued to attack the lands of the two Northumbrian kingdoms.

According to Bede, Osric and Eanfrith only ruled their respective kingdoms for about one year (c. 632 or 633 CE). Bede writes that both Eanfrith and Osric shamefully abandoned the Christian faith for their ancestral gods. Bede blames this apostasy for their swift downfalls. Osric seems to have besieged Cadwallon in an unnamed fortress or town, but Cadwallon attacked and killed Osric and scattered his forces. At some point later in the same year, Eanfrith went to negotiate a peace with Cadwallon, bringing with him only twelve warriors, and Cadwallon had them all killed.

Following Eanfrith's death, Oswald returned from exile and claimed the throne of Bernicia. Bede writes that Oswald returned to Bernicia with only a small army. It is possible that he was supported in his bid for power by Scottish and Pictish allies as well as his own retainers. Oswald met Cadwallon's forces at a place called Heavenfield, near Hexham. Bede writes that Cadwallon's force was much larger, but that Oswald was aided by God. On the night before the battle, Oswald erected a large wooden cross and he and his troops prayed to the Christian God for victory. At least one account mentions a vision of Saint Columba appearing to Oswald, assuring him that he would be victorious.

The Battle of Heavenfield took place the next day, and Oswald's forces won a crushing victory. Cadwallon himself was killed and his supporters thoroughly routed. Oswald's counsellors all agreed to be baptised following the battle, and Oswald took control of both Bernicia and Deira, reuniting the Northumbrian kingdoms. Bede claims that Oswald held imperium over virtually all of the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms during his reign, as well exerting influence over neighbouring Celtic lands. Oswald is referred to as Bretwalda in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The term Bretwalda (brytanwalda or bretenwealda) refers to Oswald's status as de facto overlord of Britain and is analogous to Bede's concept of imperium.

Oswald & Christianity

Oswald fully embraced the Christian faith as few other northern Anglo-Saxon kings had before him. Bede considers Oswald the saintliest of all the kings he examines in the Historia Ecclesiastica. His father died a pagan, and even Edwin had only been baptised after becoming king. Meanwhile, Oswald was baptised long before coming into power. As a result of his time spent in Dal Riata and beyond, Oswald allied himself with the Celtic Christian faith centred around the monastery of Iona. This brand of Christianity stood in marked contrast with the Rome-oriented community centred in Canterbury to the south, founded by Saint Augustine the Lesser in 597 CE. The rivalry between these factions would come to a head, well after Oswald's death, at the Synod of Whitby in 664 CE.

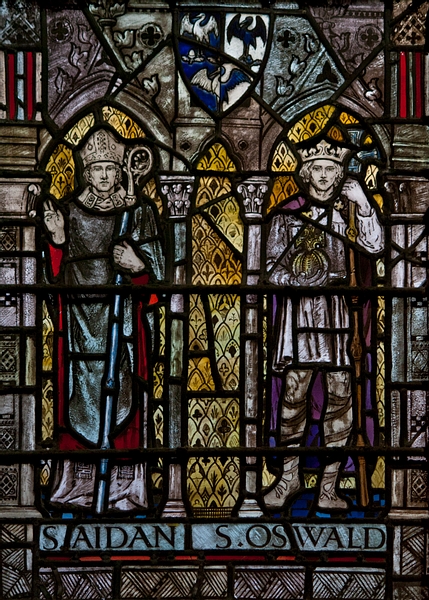

Oswald requested a bishop from Iona rather than from Canterbury. At first, the monastery sent a man named Corman who proved to be too austere and rigid. Thus, he was recalled, and in his place the community of Iona sent Aidan. Upon his arrival in Northumbria, the seat of Aidan's diocese was founded on the island of Lindisfarne, which lay not far from the royal seat of Bamburgh. While Bede was critical of certain aspects of the Celtic Christian tradition (he was more closely allied with Rome than the northern church of Oswald's day), he greatly admired Aidan. Bede writes that Oswald went so far as to translate for Aidan during many of his sermons, as Aidan could not yet speak English.

Bede also writes that Oswald was a friend to the poor. He also vigorously promoted the Christian faith beyond his own borders. He stood as godfather to the West Saxon king Cynegils (r. c. 611-642 CE) upon his baptism in Dorchester and also married Cynegils' daughter. This speaks of Oswald's status as overlord over the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms at this point in his reign.

Death

Oswald was killed at the Battle of Maserfield (Maserfelth) on August 5, c. 641 or 642 CE. Bede writes that he had reigned for eight years and was 38 years old at the time of his death. Though details of the conflict are scant, the battle was fought between Oswald's forces and the army of Penda of Mercia, who had also taken part in the victory over Edwin roughly nine years earlier. Bede writes that upon his death Oswald prayed for the souls of his warriors. After the battle, the pagan Penda had Oswald's head and hands cut off and displayed as trophies. This has been interpreted by some as a possible offering to the pagan god Woden.

The location of the battle is not precisely known but is traditionally identified with modern-day Oswestry. At the time of Oswald's death, Oswestry would have been located in the territory of the Welsh kingdom of Powys. This suggests that Oswald was leading an attack well beyond his borders and thus conflicts with Bede's account of a saintly king. It also suggests that Welsh troops may have supported Penda against Oswald. Bede writes that Oswald was fighting a just war at the time of his death, but he is virtually silent on the causes of the conflict.

Oswald's death shattered Northumbrian supremacy just as Edwin's death had nine years before. Bernicia and Deira once again split between the two traditional royal houses, with Oswald's younger brother Oswiu ascending to the Bernician throne. Penda and the Mercians would exert considerable authority over the neighbouring kingdoms for much of the next decade. It was not until c. 655 CE that Oswiu would finally defeat and kill Penda at the Battle of the Winwaed.

Veneration

Oswald's sainthood followed soon after his death at Maserfield. Though Bede took pains to depict Oswald as holy in life, he and later chroniclers recount a catalogue of miracles associated with his martyrdom. Soil from the spot where Oswald was killed was said to have had miraculous healing properties. According to the 12th-century monk Reginald of Durham, Oswald's right arm was carried off by a bird and dropped near a tree. A spring formed where Oswald's arm landed, and both the spring and the tree exhibited healing powers. Splinters from the cross at Heavenfield were also said to have displayed healing powers. There has been some scholarly debate over whether the miraculous properties of Oswald's relics reflect pagan Germanic notions of kingship.

Oswald's relics were moved several times. According to Bede, Oswald's body was brought to Bardney Abbey in Lindsey where the monks initially refused to take the body in, as Oswald had been an enemy of the Kingdom of Lindsey during his lifetime. However, a miraculous beam of light encompassing the body validated Oswald's status as a saint and changed the monks' minds. Oswald's head is believed to be interred in Durham Cathedral, though there are several other churches who claim to possess his head in England and on the Continent. His right arm was said to have remained undecayed after his death and was eventually enshrined in Peterborough Abbey. Oswald's Feast Day is celebrated on August 5.

Oswald's status as a saintly Christian king loomed large in the imaginations of later generations. Not only were his efforts in life essential for the spread of Christianity in Northumbria and throughout England but he served as a model of Christian kingship for centuries to come. For Bede, Oswald was the epitome of proper kingship in the Historia Ecclesiastica. The royal family of Wessex seems to have taken Oswald as a model as well in the late 9th and early 10th centuries CE. The royal house of Wessex took pains to acquire Oswald's relics for monasteries and churches they founded, and at least one of these churches, St. Oswald's Priory in Gloucester, was named after the king. Aethelstan (r. c. 924-927 CE) was an enthusiastic patron of Oswald's cult. How much of Oswald's legacy is due to his own actions or due to Bede's influential portrait is the subject of debate. In either case, the figure of the saintly king martyred in battle against a pagan enemy proved to be a resilient symbol in later centuries when Christian English kings contended with heathen Viking invaders.