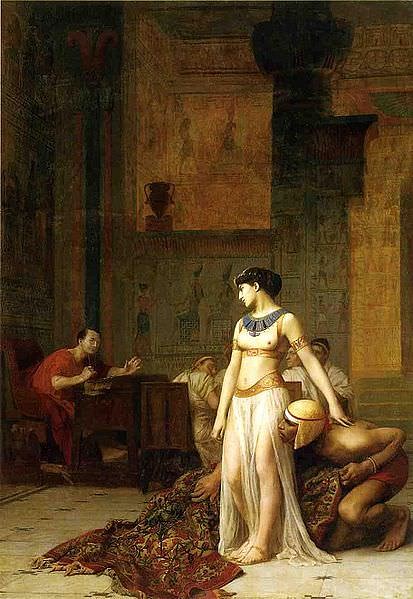

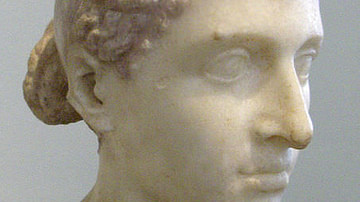

The rich lands of Egypt became the property of Rome after the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE, which spelled the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty that had ruled Egypt since the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE. After the murder of Gaius Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, the Roman Republic was left in turmoil. Fearing for her life and throne, the young queen joined forces with the Roman commander Mark Antony, but their resounding defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE brought the adopted son and heir apparent of Caesar, Gaius Julius Octavius (Octavian), to the Egyptian shores. Desperate, Cleopatra chose suicide rather than face the humiliation of capture. According to one historian, she was simply on the wrong side of a power struggle.

Early Relations with Rome

Rome's presence in Egypt actually predated both Julius Caesar and Octavian. The Romans had been involved periodically in Egyptian politics since the days of Ptolemy VI in the 2nd century BCE. The history of Egypt, dating from the ousting of the Persians under Alexander through the reign of the Ptolemys and the arrival of Julius Caesar, saw a nation suffer through conquest, turmoil, and inner strife. The country had survived for decades under the umbrella of a Greek-speaking ruling family. Although a center of culture and intellect, Alexandria was still a Greek city surrounded by non-Greeks. The Ptolemys, with the exception of Cleopatra VII, never traveled outside the city, let alone learn the native tongue. For generations, they married within the family, brother married sister or uncle married niece.

Ptolemy VI served with his mother, Cleopatra I, until her unexpected death in 176 BCE. Despite having serious troubles with a brother who challenged his right to the throne, he began a chaotic rule of his own. During his reign, Egypt was invaded twice between 169 and 164 BCE by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV; the invading army even approached the outskirts of the capital city of Alexandria; however, with the assistance of Rome, Ptolemy VI regained token control. While the next few pharaohs made little if any impact on Egypt, in 88 BCE the young Ptolemy XI succeeded his exiled father, Ptolemy X. After awarding both Egypt and Cyprus to Rome, Ptolemy XI was placed on the throne by the Roman general Cornelius Sulla and ruled with his step-mother Cleopatra Berenice until he murdered her. Ptolemy XI's ill-advised relationship with Rome caused him to be despised by many Alexandrians, and he was therefore expelled in 58 BCE. However, he eventually regained the throne but was only able to remain there through kickbacks and his ties to Rome.

When the Roman commander Pompey was soundly defeated by Caesar in 48 BCE at the Battle of Pharsalus, he sought refuge in Egypt; however, to win the favor of Caesar, Ptolemy VIII killed and beheaded Pompey. When Caesar arrived, the young pharaoh presented him with Pompey's severed head. Caesar reportedly wept, not because he mourned Pompey's death but supposedly had missed the chance of killing the fallen commander himself. Also, according to some sources, in his eyes, it was a disgraceful way to die. Caesar remained in Egypt to procure the throne for Cleopatra as Ptolemy's actions had forced him to side with the queen against her brother. With the defeat of the young Ptolemy, the Ptolemaic kingdom became a Roman client state, but immune to any political interference from the Roman Senate. Visiting Romans were treated well, even 'pampered and entertained' with sightseeing tours down the Nile. Unfortunately, there was no saving one Roman who accidentally killed a cat - sacred by tradition to the Egyptians - he was executed by a mob of Alexandrians.

History and Shakespeare have recounted ad nauseam the sordid love affair between Caesar and Cleopatra; however, his unexpected assassination forced her to seek help in safeguarding her throne. She chose incorrectly; Antony was not the one. His arrogance had brought the ire of Rome. Antony believed Alexandria to be another Rome, even choosing to be buried there next to Cleopatra. Octavian rallied the citizens and Senate against Antony, and when he landed in Egypt, the young commander became the master of the entire Roman army. His victory over Antony and Cleopatra awarded Rome with the richest kingdom along the Mediterranean Sea. His future was guaranteed. The country's overflowing granaries were now the property of Rome; it became the 'breadbasket' of the empire, the 'jewel of the empire's crown.' However, according to one historian, Octavian believed that Egypt was now his own private kingdom, he was the heir of the Ptolemaic dynasty, a pharaoh. Senators were even prohibited from visiting Egypt without permission.

Egypt Becomes a Roman Province

With the end of a long civil war, Octavian had the loyalty of the army and in 29 BCE returned to Rome and the admiration of its people. The Republic had died with Caesar. With Octavian - soon to be acclaimed as Augustus - an empire was born. It was an empire that would overcome poor leadership and countless obstacles to rule for almost five centuries. He would restore order to the city, becoming its 'first citizen,' and with the blessing of the Senate, govern without question. Upon his triumphant march into the city, the emperor displayed the spoils of war. The conquering hero adorned in a gold-embroidered toga and flowered tunic rode through the city streets in a chariot drawn by four horses. Although Cleopatra was dead (he had hoped to display and humiliate her in public), an effigy of the late queen, reclining on a couch, was placed on exhibit for all to see. The queen's surviving children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus (Caesarion had been executed), walked in the procession. Soon afterwards, Augustus ordered the immediate construction of both a temple deifying Caesar (built on the spot where he had been cremated) and a new Senate house, the Curia Julia; the old one had been torched following Caesar's funeral.

Emperor Augustus took absolute control of Egypt. Although Roman law superseded all legal Egyptian traditions and forms, many of the institutions of the old Ptolemaic dynasty remained with a few fundamental changes in its administrative and social structure. The emperor quickly filled the ranks of the administration with members of the equestrian class. With a flotilla on the Nile and a garrison of three legions or 27,000 troops (plus auxiliaries), the province existed under the leadership of a governor or prefect, an appointee (as were all major officials) of the emperor. Later, since the region saw few outside threats, the number of legions was reduced. Strangely, the first governor, Cornelius Gallus, unwisely made 'grandiose claims' about his victorious campaign into the neighboring Sudan. Augustus was not happy, and the governor mysteriously committed suicide - the area's frontier would thereafter remain fixed.

Social & Cultural Divisions

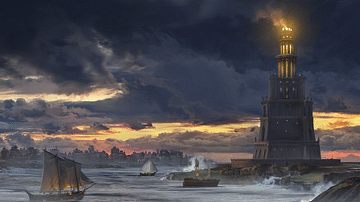

Egyptian temples and priesthoods kept most of their privileges, although the imperial cult did make an appearance. While the mother-city of each region was permitted partial self-government, the status of many of the province's major towns changed under Roman occupancy with Alexandria (the city's population would reach 1,000,000) enjoying the greatest concessions. Augustus maintained a registry of the 'Hellenized' residents of each city. Non-Alexandrians were simply referred to as Egyptians. Rome also introduced a new social hierarchy, one with serious cultural overtones. Hellenic residents - those with Greek ancestry - formed the socio-political elite. The citizens of Alexandria, Ptolemais, and Naucratis were exempt from a newly introduced poll-tax while the 'original settlers' of the mother-cities were granted a reduced poll-tax.

The main cultural separation was, as always, between the Hellenic life of the cities and the Egyptian-speaking villages; thus, the bulk of the population remained, as it had been, the peasants who worked as tenant farmers. Much of the food produced on these farms was exported to Rome to feed its ever-growing population. As it had for decades, the city needed to import food from its provinces – namely Egypt, Syria, and Carthage - to survive. The food, together with luxury items and spices from the East, ran down the Nile to Alexandria and then to Rome. By the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, large private estates emerged operated by the Greek landowning aristocracy.

Over time this strict social structure would be questioned as Egypt, Alexandria especially, saw a significant change in its population. As more Jews and Greeks moved into the city, problems arose that challenged the patience of the emperors in Rome. The reign of Emperor Claudius (41-54 CE) saw riots emerge between the Jews and the Greek-speaking residents of Alexandria. His predecessor, Caligula, stated that the Jews were to be pitied, not hated. Later, under Emperor Nero (54-68 CE) 50,000 were killed when Jews tried to burn down Alexandria's amphitheater – two legions were necessary to quell the riot.

Attitude Towards Roman Control

Initially, Egypt was accepting of Roman control. Its capital of Alexandria would even play a major role in the ascendancy of one of the empire's most famous emperors. After the suicide of Nero in 68 CE, four men would vie for the throne – Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian – in what became known as the Year of the Four Emperors. In the end, the battle fell to Vitellius and Vespasian. With hopes of delaying valuable shipments of grain to Rome, Vespasian traveled to Alexandria. At the same time, Mucianus, a Roman commander and ally of Vespasian, marched into Rome. The defeated Vitellius was captured, and while pleading for his life, dragged through the streets, tortured, and killed. His body was thrown into the Tiber. Still in Alexandria, the armies of Vespasian unanimously declared him emperor.

In 115 CE, however, there were a number of Jewish riots in Cyrenaica, Cyprus, and Egypt, voicing discontent with Roman rule and rampaging against pagan sanctuaries. The riots were eventually suppressed by Roman troops; however, thousands of Romans and Greeks were killed in what became known as the Babylonian Revolt or Kitos War. Dissatisfaction with Roman control became part of the Egyptian psyche. Until the fall of Rome in the west, revolt and chaos would haunt the Egyptian prefects. In the early 150s CE, Emperor Antonius Pius quelled rebellions in Mauretania, Dacia, and Egypt. Over a century later, in 273 CE, Emperor Aurelian suppressed another Egyptian uprising. After the division of the empire under Diocletian, revolts broke out in 295 and 296 CE.

Two major disasters hit Egypt, disrupting Roman control. The first was the Antonine plague of the 2nd century CE, but the more serious of the two came in 270 CE with an invasion from the unlikeliest of all invaders, Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, an independent city on the border of Syria. When its king Septimius Odaenathus died under suspicious circumstances, his wife took charge as regent, leading an army in the conquest of Egypt (she ousted and beheaded its prefect), Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia and proclaiming her young son Septimus Vaballathus emperor. One action that brought the ire of Rome came when she cut off the city's corn supply. The new emperor of Rome, Aurelian, would finally defeat her in 271 CE. Her death, however, is shrouded in mystery. One story had the emperor bringing her to Rome as a prisoner (she was given a private villa) while another has her dying en route to the city.

The End of Roman Egypt

When emperor Diocletian came to power in the late 3rd century CE, he realized that the empire was far too big to be ruled efficiently, so he divided the empire into a tetrarchy with one capital, Rome, in the west and another, Nicomedia, in the east. While it would continue supplying grain to Rome (most resources were diverted to Syria), Egypt was placed in the eastern half of the empire. Unfortunately, a new capital in the east, Constantinople, became the cultural and economic center of the Mediterranean. Over time the city of Rome fell into disarray and susceptible to invasion, eventually falling in 476 CE. The province of Egypt remained part of the Roman/Byzantine Empire until the 7th century when it came under Arab control.