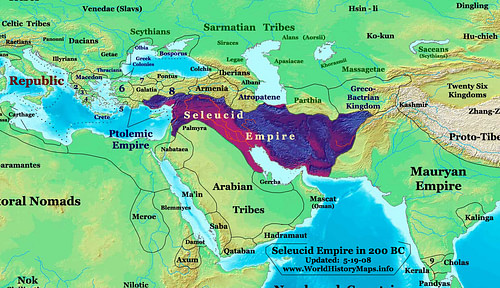

The Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) was the vast political entity established by Seleucus I Nicator ("Victor" or "Unconquered", l. c. 358-281 BCE, r. 305-281 BCE), one of the generals of Alexander the Great who claimed a part of his empire after Alexander's death in 323 BCE.

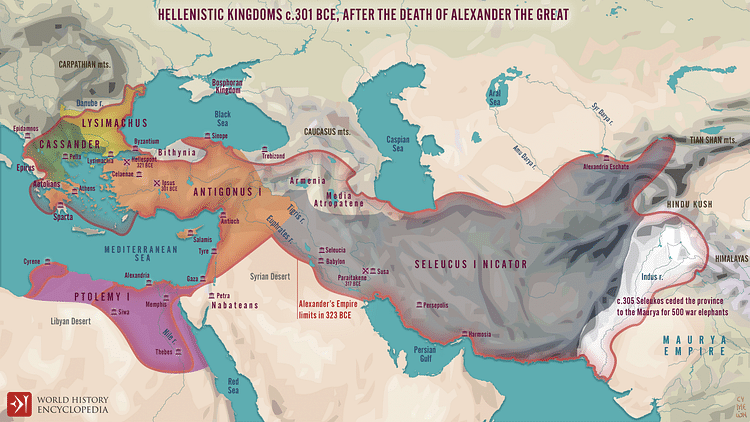

When Alexander died, he left no certain successor to his kingdom but, allegedly, claimed it should go to "the strongest". This resulted in the conflict between his top generals known as the Wars of the Diadochi ("successors") which would divide Alexander's vast territory between five of them: Cassander, Ptolemy I Soter, Lysimachus, Antigonus, and Seleucus.

Of the four, Seleucus was arguably the most successful in that he accomplished what Alexander had set out to do: the creation of a multi-national empire which merged eastern and western cultures harmoniously. The Seleucid Empire, at first, was marked by religious and cultural tolerance, efficient bureaucracy, lucrative trade, and expansion through military campaign, creating a realm stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indus Valley.

As with Rome, however, the vast expanse of the empire, and the desire for autonomy of many of the different regions, eventually became too great for the central government to control and the Seleucid Empire began to fracture. Adding to its problems was the rise of Rome as a Mediterranean superpower which could not tolerate another and more significantly, the loss of Seleucus I's original vision by his successors. The Seleucid Empire began to crumble after 100 BCE and was finally toppled by Rome through the efforts of its general Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-48 BCE) in 63 BCE.

Foundation & Expansion

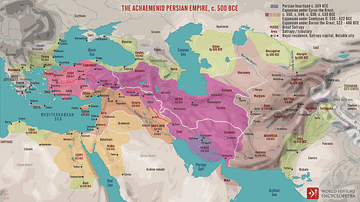

Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) had conquered the Achaemenid Persian Empire by 330 BCE and, after his death, his generals were left with an immense realm, which encompassed Greece, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Egypt, the Levant, and Central Asia. After a power struggle, they divided it between themselves with Cassander taking Greece, Ptolemy I Soter Egypt, Lysimachus Thrace and Anatolia, Antigonus – who had held Anatolia - dying at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE, and Seleucus, having claimed Babylon as his own, taking Mesopotamia and Central Asia.

Alexander had extended his reach all the way to India, establishing cities and leaving satraps (governors) to administrate. In c. 305 BCE, King Chandragupta Maurya took back a number of these regions and Seleucus launched the Seleucid-Mauryan War (305-303 BCE) which resulted in a treaty whereby Seleucus gave up the contested regions in return for trade agreements and respect for his borders.

Seleucus seemed to be everywhere at once, taking whatever regions he could from his former comrades-in-arms, especially Antigonus, until the latter's defeat at Ipsus in 301 BCE (a victory largely resulting from Seleucus' use of war elephants he had received from Chandragupta by treaty). By 300 BCE, Seleucus controlled Mesopotamia (including Syria), Cappadocia, and Armenia. He founded a capital, the city of Antioch, on the Orontes River – which would administer the western part of his realm – and the city of Seleucia, on the Tigris River, to control the eastern regions. Seleucus ruled from Antioch and made his son, Antiochus I Soter (co-rule 291-281 BCE, r. 281-261 BE), co-ruler from Seleucia.

In c. 282 BCE, Seleucus received two guests from Anatolia – Ptolemy Ceraunos (d. 279 BCE) and his sister Lysandra – asking for his help. Both were part of the royal court of Lysimachus and claimed he had unjustly killed his own son, Agathocles, on trumped-up charges of treason and, as a fellow monarch, Seleucus should avenge the prince's death. Although this was none of Seleucus' business, the supplicants were children of Ptolemy II, son of his former comrade Ptolemy I Soter who had sheltered Seleucus in Egypt in the early years of the Wars of the Diadochi; this gave Seleucus the excuse he needed to take their side, punish Lysimachus, and add Anatolia to his empire.

Seleucus marched on Anatolia, taking it from Lysimachus and killing him. Seleucus was now the last remaining of the Diadochi and, after consolidating his hold on Anatolia, prepared for an invasion of Greece. In 281 BCE, as he was in the middle of these preparations, he was assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunos who then claimed Anatolia as his own before fleeing to Greece and proclaiming himself king of Macedon. His reign was short-lived, however, and he was killed in battle in 279 BCE.

Development & Government

Antiochus I Soter now became emperor and continued his father's policies of encouraging a homogeneous empire which blended Hellenistic cultural values with those of the Near East. Scholar Cormac O'Brien describes the Seleucid policy:

To rule as Greeks in an immense sea of non-Greeks would have been foolish, if not impossible, and so the Seleucids became both. With their own administration forming merely the newest of a series of ethnic layers that went back centuries, Seleucus and his successors were happy to embrace the cults, gods, and practices of the venerable states that came before them…That was the spirit of Hellenism – the amalgamation of West and East that forged a dynamic new era. And the Seleucid enterprise was its clearest manifestation. (204)

The Achaemenid Persian Empire had functioned as well as it did through a policy of centralized government with decentralized administration. The king (emperor) was the supreme power but took counsel from his advisors who passed his decrees to secretaries who then relayed these to regional governors (the satraps). Each Satrapy was administered by a governor who only had authority over bureaucratic-administrative matters while another official – a trusted general – oversaw military/police matters. This division of responsibilities in each satrapy reduced the chance of a regional governor amassing enough power from a loyal army to attempt a coup. The governor of a region lacked military power and the general lacked funds to bribe an army into backing a power grab.

Alexander had maintained this form of government and Seleucus continued it. Even so, after his death, regions such as Armenia and Cappadocia saw a chance to break away from the empire and revolted. At the same time, Ptolemy II of Egypt lay claim to Syria and its rich trade routes and declared war on Antiochus I Soter and, in c. 278 BCE, King Nicomedes of Bithynia (r. 278-255 BCE) invited the Celts into Anatolia to help him oust his brother and, afterwards, they then went about sacking cities and destroying the fields and crops of anyone who could not – or would not – pay them protection money.

Antiochus I Soter defeated the Celts at the so-called Battle of the Elephants (c. 275 BCE) in which he released his sizeable contingent of war elephants on his enemy, routing them. The Celts quickly sought peace and were employed as mercenaries against Ptolemy II and the rebel states. Antiochus followed his father's example in elevating his son, Antiochus II Theos (r. 261-246 BCE), to co-rule as they worked to hold the empire together - and they succeeded until close to the end of Antiochus II Theos' reign.

Arsaces of the Parni tribe of Parthia revolted and broke away from the empire in 247 BCE, proclaiming himself Arsaces I of Parthia (r. 247-217 BCE), and establishing the core state of what would later become the Parthian Empire. In 245 BCE, regional governor Diodotus of Bactria (d. 239 BCE) seceded, creating the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom on the far eastern border. Antiochus II Theos' successors, Seleucus II Callinicus (r. 246-225 BCE) and Seleucus III Ceraunus (r. 225-223 BCE) could do nothing to bring the breakaway states back under their control and, at the same time, were struggling with a failing economy and the growing power of the Celts – formerly somewhat under Seleucid control – who had established themselves in the Anatolian region of Galatia.

Antiochus III the Great

The Seleucid Empire had been struggling since the death of Seleucus but another power was rapidly on the rise. While the Seleucids were masters of land battle and trade, the North African city of Carthage ruled the seas both commercially and militarily. In 264 BCE, Carthage came into conflict with the small city-state of Rome over a dispute between two kingdoms in Sicily which each had a vested interest in. This conflict erupted into the First Punic War (264-241 BCE) which concluded with Rome as the new superpower and Carthage, in defeat, forced to pay a heavy war indemnity.

Whatever happened with Rome and Carthage, however, was little concern to the Seleucid rulers when compared with their struggles to keep the empire intact. Even with all the safeguards in place against revolt, and the lenient policies regarding the peoples' cultural and religious values, the Seleucids still could not control people's desire for freedom to chart their own fate.

The Seleucid's decline was halted, then reversed, by the son of Seleucus II Callinicus, Antiochus III (r. 223-187 BCE, known as The Great), who personally led his troops throughout the empire, defeating upstart states and returning them to the fold. For over twenty years (c. 219-199 BCE), Antiochus III campaigned from the Levant to India, subduing Bactria and Asia Minor (a campaign that included his siege of Sardis, 215-213), making peace with Parthia, and winning Judea and Syria from Egypt.

While Antiochus III was restoring his empire to its former glory, Rome again went to war with Carthage in the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE). Hannibal Barca (l. 247-183 BCE), a sworn enemy of Rome and Carthage's greatest general, had broken the peace by marching on Roman Saguntum in Spain in 218 BCE and then led his army over the Alps to invade Italy. He was only finally defeated through the skill of the Roman general Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE.

Hannibal had been helped by Philip V of Macedon (r. 221-179 BCE) who, in c. 205 BCE, allied himself with Antiochus III to defeat Egypt. Although the alliance worked well enough against the Egyptian presence in the Levant and Judea, Antiochus III was dissuaded by the Romans from invading Egypt, which was a friend of Rome and its major source of grain. Once Rome defeated Carthage, they punished Philip V, charging him with aiding their enemy and, further, with tyranny over the Greeks. Claiming they were liberating the Greek city-states, they invaded Greece and defeated Philip V at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE.

Antiochus III suspected he would be next on Rome's list and decided to strike first. He had been encouraged in this by Hannibal who, after Zama, arrived at his court and became one of his most important councilors until Rome demanded his surrender and he killed himself. Antiochus III, even without Hannibal's guidance, believed he could beat Rome. He crossed the Hellespont and met the Romans in battle at Thermopylae in 191 BCE and then at Magnesia in 190 BCE. He was defeated in both engagements with heavy losses and returned home with no choice now but to accept whatever terms Rome offered. As per the Treaty of Apamea of 188 BCE, he was forced to withdraw from Anatolia, reduce his territories to the boundary of the Taurus Mountains (thus losing all the regions to the north and west), pay a large war indemnity, and agree to never make war in Europe again. The treaty also stipulated annual hostages from the Seleucid court be sent to Rome, a policy which would influence later Seleucid monarchs. Antiochus III died on campaign in the east shortly after this, killed while robbing a temple in Luristan in 187 BCE as part of his efforts to raise money to pay the indemnity.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes & the Maccabees

Antiochus III's son and successor, Seleucus IV Philopator (r. 187-175 BCE), continued the efforts to pay off the war debt to the extent that this became his primary focus. He was assassinated in 175 BCE and rule passed to Antiochus III's other son, Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175-164 BCE). Antiochus IV had been sent to Rome as a hostage following the Treaty of Apamea and knew Roman policies and practices first-hand.

He attacked Egypt, taking most of the country, in response to Egypt's aggression in Syria but allowed the king, Ptolemy VI, to remain in power as his puppet. The social order was thereby maintained, grain would continue flowing to Rome without interruption, and so – as Antiochus has hoped - the Romans did not interfere. Ptolemy VI, however, joined forces with his brother, Ptolemy VII, in an effort to throw off Seleucid rule, prompting Antiochus IV to return for a second campaign.

He was halted by an aged ambassador from Rome, Gaius Popillius Laenas who, according to Polybius (29.27), told him the Roman senate wanted him to withdraw. Laenas refused to greet Antiochus IV in any way befitting a monarch and, instead, drew a circle around him in the dirt with a stick, telling him that he needed a reply to the senate before Antiochus IV should leave the circle and, if that reply was not in accord with Rome's wishes, he would be considered Rome's enemy. Antiochus IV knew what war with Rome would mean and agreed to withdraw, leaving Egypt in peace.

At this same time (c. 168 BCE), a simmering conflict was going on in the Seleucid province of Judea between conservative Jews who sought to maintain their religious and cultural heritage and Hellenized Jews who had adopted Seleucid mannerisms and customs. This tension finally came to a head in a dispute over the position of the high priest of the temple in Jerusalem. The high priest had traditionally come from the Oniad family and in c. 175 BCE, one of its members, Joshua, paid Antiochus IV to promote him to the position and depose his brother, Onias III, the rightful priest. Antiochus IV agreed, Joshua then Hellenized his name to Jason, and encouraged Greek customs in the city and around the temple, notably building a gymnasium – where people exercised in the nude which was considered shameful to the Jews – in the holy precinct.

Antiochus III had continued Seleucus I's respect for the religious customs of all the people of the empire but Antiochus IV had no such regard. When Jason sent a messenger, Menelaus, to Antiochus IV with a sum of money, Menelaus offered the king more to depose Jason and choose him as High Priest and Antiochus IV agreed to this easily. Menelaus took control of the temple but Jason raised an armed group of supporters and attacked. Antiochus IV, never known for his patience or consideration, then claimed that the temple should be dedicated to him and decreed sacrifices made there would be in his honor.

This action prompted the Maccabean Revolt (c. 168/167 to c.160 BCE), led by Judas Maccabaeus, to restore Judaism and rededicate the temple, an event commemorated in the present day by the festival of Hanukah. Antiochus IV was unable to restore order after causing the chaos, dying in 163 BCE and leaving the problems of the rise of the Hasmonean Dynasty in Judea and the ever-shrinking empire to his successors.

Decline & Fall

The Seleucid monarchy after Antiochus III seemed to forget, or purposefully ignored, the vision of Seleucus I, concentrating on their own self-aggrandizement at the expense of the people. Between 163 and 145 BCE three kings ruled, all of whom were more concerned with defending their position than actual governance. While the monarchy openly fought or intrigued against each other, piracy became a viable option for many trying to make a living in Cilicia, giving rise to the Cilician pirates, a coalition of many different nationalities, which now routinely attacked ships and ports around the Mediterranean.

The Cilician pirates were encouraged and protected by Diodotus Tryphon (r. 140-138 BCE) who had taken power from Antiochus VI Dionysius (145-140 BCE) who had done the same, since the pirates trafficked in the slave trade and the Seleucids needed slaves as much as any other power of the era. The chaos of the monarchy at this time is exemplified in the figure of Cleopatra Thea (l. c. 164-121 BCE) who was part pawn and part player in the court intrigue of five separate rulers. Cleopatra was first the wife of Alexander Balas (r. 150-145 BCE) before her father, Ptolemy VI, invaded Syria, killed Alexander, and then married her to Demetrius II Nicator (r. 145-138, 129-126 BCE) who was captured and held by the Parthians until 129 BCE.

While he was in captivity, his brother, Antiochus VII Sidetes (r. 138-129 BCE), married Cleopatra to gain the throne. The Parthians released Demetrius to encourage a dynastic dispute but Antiochus VII Sidetes was killed by them in battle at the same time. Demetrius regained power for three years before he failed in a campaign against Egypt and was betrayed by Cleopatra Thea and murdered. When his son, Seleucus V Philometor (r. 126-125 BCE) came to power, she had him killed and installed her son Antiochus VIII Grypos (r. 125-96 BCE) as king. She tried to kill him when he would not bend to her will but he forced her to drink the poison cup she offered.

By this time, there was no longer any Seleucid Empire remotely resembling the vision of Seleucus I, only a small kingdom in Syria, which continued to use that title. Rome became more involved in the surrounding region during the Mithridatic Wars (89-63 BCE) against the king Mithridates VI of Pontus (r. 120-63 BCE) and Mithridates VI's son-in-law, Tigranes the Great of Armenia (r. 95-56 BCE), noticing that neither side seemed to care what happened to the Syrian kingdom, invaded and added it to his own. His control was short-lived, however, and as soon as the general Pompey had defeated Mithridates he turned his attention to Syria and Anatolia, making both of them Roman provinces and ending the Seleucid monarchy at about the same time he destroyed the Cilician pirates.

The last king of the Seleucids was Philip II Philoromaeus (r. 65-63 BCE) about whom little is known outside of a hopeless attempt to maintain his position, which exemplifies the Seleucid monarchy on the whole after Antiochus III. Once Seleucus I's grand vision of a vast, multicultural empire living in peace had been lost – starting with the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes - the rest of the empire's royal history was marked by arrogance, neglect of the people, and petty power grabs which finally left them with nothing.