The Negative Confession (also known as The Declaration of Innocence) is a list of 42 sins which the soul of the deceased can honestly say it has never committed when it stands in judgment in the afterlife. The soul would recite these in the presence of the gods who weighed their truth in deciding one's fate.

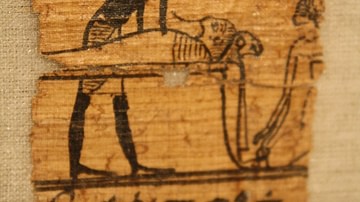

The most famous list comes from The Papyrus of Ani, a text of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, prepared for the priest Ani of Thebes (c. 1250 BCE) and included among the grave goods of his tomb. It includes a number of chapters from the Book of the Dead but not all of them. These omissions are not a mistake, nor have sections of the manuscript been lost, but are the result of a common practice of creating a funerary text specifically for a certain person's use in the afterlife. The Negative Confession included in this text follows this same paradigm as it would have been written for Ani, not for anyone else.

Although The Egyptian Book of the Dead is often described as 'the ancient Egyptian Bible' or a scary 'book of the occult,' it is actually neither; it is a funerary text providing instruction to the soul in the afterlife. The actual translation of the work's title is The Book of Coming Forth by Day. Since the ancient Egyptians believed that the soul was eternal and one's life on earth was only a brief aspect of an eternal journey, it was considered vital that the soul have some kind of guidebook to navigate the next phase of existence.

On earth, it was understood, if one did not know where one was going, one could not arrive at the desired destination. The Egyptians, being eminently practical, believed one would need a guide in the afterlife just as one did on earth. The Egyptian Book of the Dead is such a guide and was provided for anyone who could afford to have one made. The poor had to make do without a text or a rudimentary work but anyone who could afford it would pay for a scribe to create a personalized guidebook.

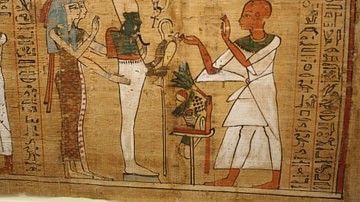

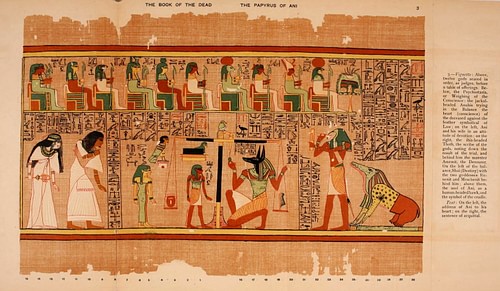

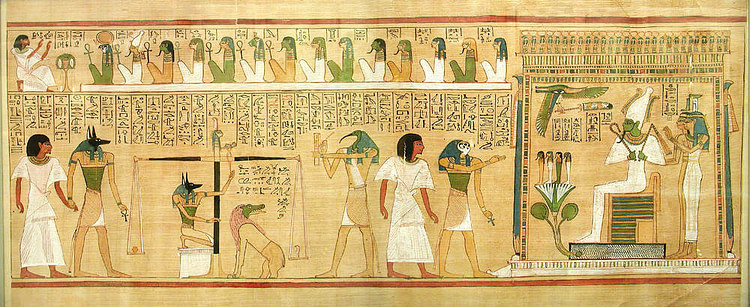

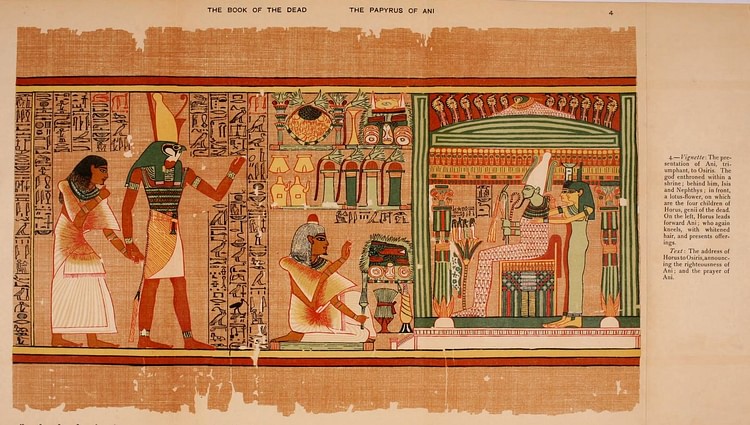

The Negative Confession appears in Spell 125 which is easily the most famous as it includes the accompanying vignette of the weighing of the heart on the scale against the white feather of ma'at. Although the spell does not describe the judgment in the Hall of Two Truths, the illustration is meant to show what the soul could expect once it arrived there and the text provided that soul with what to say and how to behave. The Confession is significant for modern-day Egyptologists in understanding ancient Egyptian cultural values in the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), but at the time it was written, it would have been considered necessary in order for one to pass through judgment before Osiris and the divine tribunal.

The Confession is thought to have developed from an initiation ritual for the priesthood. The priests, it is claimed, would need to recite some kind of formulaic list in order to prove themselves ritually pure and worthy of their vocation. Although some evidence exists to support this claim, the Negative Confession as it stands seems to have developed in the New Kingdom of Egypt, when the cult of Osiris was fully integrated into Egyptian culture, as the way for the deceased to justify themselves as worthy of paradise in the afterlife.

Judgment in the Afterlife

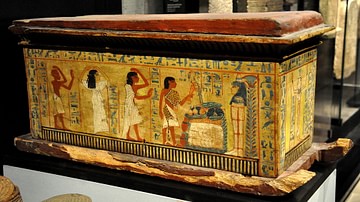

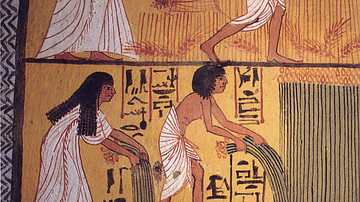

Funerary texts had been written in Egypt since the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) when the Pyramid Texts were inscribed on tomb walls. The Coffin Texts followed later in the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) and these were developed for The Egyptian Book of the Dead in the New Kingdom. The purpose of these texts was to orient and reassure the soul of the deceased once it awoke in its tomb following the funeral. The soul would be unused to the world outside of the body and would need to be reminded of who it had been, what it had done, and what it should do next.

In most depictions, the soul would be led from the tomb by Anubis to stand in judgment before Osiris, Thoth, and the 42 Judges. Depictions of this process show the souls of the dead standing in a line, administered to by various deities such as Qebhet, Nephthys, Isis, and Serket, while they wait their turn to come before Osiris and his golden scales. When one's turn came, one would stand before the gods and recite the Negative Confession - each one addressed to a specific judge - and then hand over one's heart to be weighed in the balances. The physical heart was always left in the body of the corpse during the embalming and mummification process for this very reason. It was thought that the heart contained one's character, one's personality, and intellect, and would need to be surrendered to the gods in the afterlife for judgment.

The heart was placed on the scale in balance against the white feather of truth and, if it was found to be lighter, one went on toward paradise; if it was heavier it was dropped onto the floor where it was eaten by the monster Amut and the soul then ceased to exist. Prior to this final judgment and one's reward or punishment, Osiris, Thoth, and Anubis would confer with the 42 Judges. This would be the point at which allowances might be made. The 42 Judges represented the spiritual aspects of the 42 nomes (districts) of ancient Egypt and it is thought that each of the confessions addressed a certain kind of sin which would have been particularly offensive in a specific nome. If the judges felt that one had been more virtuous than not, it was recommended that the soul be justified and allowed to pass on.

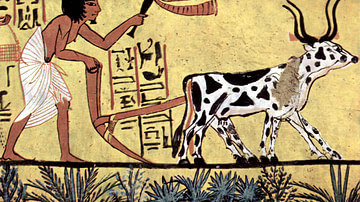

The details of what happened next vary from era to era. In some periods, the soul would have to navigate certain dangers and traps to reach paradise while, in others, one simply walked on to Lily Lake after judgment and, after a final test, was taken across to paradise. Once there, the soul would enjoy an eternity in a world which perfectly reflected one's life on earth. Everything one thought had been lost would be returned, and souls would live in peace with each other and the gods, enjoying all of the best aspects of life for eternity. Before one could reach this paradise, however, the Negative Confession had to be accepted by the gods and this meant one had to be able to sincerely mean what was said.

The Different Confessions

There is no standard Negative Confession. The confession from The Papyrus of Ani is the best known only because that text is so famous and so often reproduced. As noted, scribes would tailor a text to the individual, and so while there was a standard number of 42 confessions, the sins which are listed varied from text to text. For example, in The Papyrus of Ani confession number 15 is "I am not a man of deceit," while elsewhere it is "I have not commanded to kill," and in another, "I have not been contentious in affairs." An officer in the military would not be able to honestly claim "I have not commanded to kill" nor would a judge or a king, and so that 'sin' would be left off their confession.

This was not weighing the confession in the deceased's favor so much as ensuring one did not condemn one's self by speaking falsely. The heart would still be weighed in the balances, after all, and any deceit would be known. The soul was therefore provided with a list it could speak truthfully in front of the gods instead of a standard inventory of sins everyone would have to recite.

Still, there are standard sins in every list such as "I have not stolen," "I have not slandered," "I have not caused pain," and other similar claims. It is also thought that these statements carried unspoken stipulations in many cases. Confession 10 in some texts reads "I have not caused anyone to weep," but this is a very difficult claim to make since one often has no idea how one's actions have affected others.

It is therefore thought that the intent of the claim is "I have not intentionally caused anyone to weep." The same could be said for a claim such as "I have not made suffering for anyone" and for the same reason. The point of the confession was to be able to honestly claim innocence of actions which were contrary to the principle of ma'at, and so, no matter what specific sins were included, one needed to be able to say one was innocent of willfully challenging the governing principle of harmony and balance in life.

The Negative Confession of Ani

Ma'at was the central cultural value of ancient Egypt which allowed the universe to function as it did. In making the confession, the soul was stating that it had adhered to this principle and that any failings were unintentional. In the following confession, Ani addresses himself to each of the 42 Judges in the hope that they will recognize his intentions in life, even if he may not always have chosen the right action at the right moment. One was not supposed to consider 'sins of omission' but only 'sins of commission' which were pursued intentionally.

The following translation is by E. A. Wallis Budge from his original work on The Egyptian Book of the Dead. Each confession is preceded by a salutation to a specific judge and the region they come from. Some of these regions, however, are not on earth but in the afterlife. Hraf-Haf, for example, who is hailed in number 12, is the divine ferryman in the afterlife.

In Ani's case, then, the 42 nomes are not fully represented (some, in fact, are mentioned twice) but the standard number of 42 is still adhered to. Prior to beginning the Confession, the soul would greet Osiris, make an assertion that it knew the names of the 42 Judges, and proclaim its innocence of wrong-doing, ending with the statement "I have not learnt that which is not." This means the person never lost faith or entertained a belief contrary to the truth of ma'at and the will of the gods.

1. Hail, Usekh-nemmt, who comest forth from Anu, I have not committed sin.

2. Hail, Hept-khet, who comest forth from Kher-aha, I have not committed robbery with violence.

3. Hail, Fenti, who comest forth from Khemenu, I have not stolen.

4. Hail, Am-khaibit, who comest forth from Qernet, I have not slain men and women.

5. Hail, Neha-her, who comest forth from Rasta, I have not stolen grain.

6. Hail, Ruruti, who comest forth from Heaven, I have not purloined offerings.

7. Hail, Arfi-em-khet, who comest forth from Suat, I have not stolen the property of God.

8. Hail, Neba, who comest and goest, I have not uttered lies.

9. Hail, Set-qesu, who comest forth from Hensu, I have not carried away food.

10. Hail, Utu-nesert, who comest forth from Het-ka-Ptah, I have not uttered curses.

11. Hail, Qerrti, who comest forth from Amentet, I have not committed adultery.

12. Hail, Hraf-haf, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have made none to weep.

13. Hail, Basti, who comest forth from Bast, I have not eaten the heart.

14. Hail, Ta-retiu, who comest forth from the night, I have not attacked any man.

15. Hail, Unem-snef, who comest forth from the execution chamber, I am not a man of deceit.

16. Hail, Unem-besek, who comest forth from Mabit, I have not stolen cultivated land.

17. Hail, Neb-Maat, who comest forth from Maati, I have not been an eavesdropper.

18. Hail, Tenemiu, who comest forth from Bast, I have not slandered anyone.

19. Hail, Sertiu, who comest forth from Anu, I have not been angry without just cause.

20. Hail, Tutu, who comest forth from Ati, I have not debauched the wife of any man.

21. Hail, Uamenti, who comest forth from the Khebt chamber, I have not debauched the wives of other men.

22. Hail, Maa-antuf, who comest forth from Per-Menu, I have not polluted myself.

23. Hail, Her-uru, who comest forth from Nehatu, I have terrorized none.

24. Hail, Khemiu, who comest forth from Kaui, I have not transgressed the law.

25. Hail, Shet-kheru, who comest forth from Urit, I have not been angry.

26. Hail, Nekhenu, who comest forth from Heqat, I have not shut my ears to the words of truth.

27. Hail, Kenemti, who comest forth from Kenmet, I have not blasphemed.

28. Hail, An-hetep-f, who comest forth from Sau, I am not a man of violence.

29. Hail, Sera-kheru, who comest forth from Unaset, I have not been a stirrer up of strife.

30. Hail, Neb-heru, who comest forth from Netchfet, I have not acted with undue haste.

31. Hail, Sekhriu, who comest forth from Uten, I have not pried into other's matters.

32. Hail, Neb-abui, who comest forth from Sauti, I have not multiplied my words in speaking.

33. Hail, Nefer-Tem, who comest forth from Het-ka-Ptah, I have wronged none, I have done no evil.

34. Hail, Tem-Sepu, who comest forth from Tetu, I have not worked witchcraft against the king.

35. Hail, Ari-em-ab-f, who comest forth from Tebu, I have never stopped the flow of water of a neighbor.

36. Hail, Ahi, who comest forth from Nu, I have never raised my voice.

37. Hail, Uatch-rekhit, who comest forth from Sau, I have not cursed God.

38. Hail, Neheb-ka, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have not acted with arrogance.

39. Hail, Neheb-nefert, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have not stolen the bread of the gods.

40. Hail, Tcheser-tep, who comest forth from the shrine, I have not carried away the khenfu cakes from the spirits of the dead.

41. Hail, An-af, who comest forth from Maati, I have not snatched away the bread of the child, nor treated with contempt the god of my city.

42. Hail, Hetch-abhu, who comest forth from Ta-she, I have not slain the cattle belonging to the god.

Commentary

As noted, many of these would carry the stipulation of intention - such as "I have never raised my voice" - in that one may have actually raised one's voice but not in unjustified anger. This same could be said for "I have not multiplied my words in speaking" which does not refer to verbosity necessarily but duplicity. Ani is saying he has not tried to obscure his meaning through wordplay. This same consideration should be used with claims like number 14 - "I have not attacked any man" - in that self-defense was justified.

Claims such as 13 and 22 ("I have not eaten the heart" and "I have not polluted myself") refer to ritual purity in that one has not participated in any activity proscribed by the gods. Number 13 could also be intended, however, as claiming one has not hidden one's feelings or pretended to be something one was not. Number 22 is sometimes translated as "I have not polluted myself, I have not lain with a man" just as number 11, dealing with adultery, sometimes adds the same line.

These lines have been cited as a condemnation of homosexuality in ancient Egypt, but such claims ignore the central focus of the Negative Confession on the individual. It might be wrong for Ani to have sexual relations with a man but not for someone else to do the same. Drunkenness was approved of in ancient Egypt, as was premarital sex, but only under certain conditions: one could get as drunk as one wished at a festival or party but not at work, and one could have as much premarital sex as one wanted but not with a person who was already married. This same may have held true for homosexual relationships. Nowhere in Egyptian literature or religious texts is homosexuality condemned.

The Egyptians valued individuality. Their mortuary rituals and vision of the afterlife were predicated on this very concept. Tomb inscriptions, monuments, autobiographies, the Great Pyramid itself, were all expressions of an individual's life and accomplishments. The Negative Confession followed this same model as it was shaped to each person's character, lifestyle, and vocation. It was hoped that everyone who was deserving would be justified in the afterlife and that it would be recognized, whatever their personal failings, that they should be allowed to continue their journey to paradise.