Forts and sieges held a key position in ancient Indian warfare. Built on considerations of strategic location, topography, and the natural advantages provided by the site, forts would be heavily supplemented with man-made fortifications. They were required not only for the security of the populace that lived in its vicinity but the kingdom as a whole. A fort could provide shelter to the king and his armies against enemies and check the invaders from advancing further into the kingdom. Protected by fortifications, a king or commander could engage the enemy with greater confidence and had a chance of repulsing him. Capturing forts was necessary as enemy capitals were usually fortified and no invader could proclaim victory without these strategic strongholds. In these engagements, the archers and elephants played the major roles. Ancient texts like the Arthashastra and the Buddhist Nikaya texts (500 BCE - 300 BCE) give valuable information on the conduct of siege warfare in ancient India including construction, assault, and defence of forts.

Purpose of the Fort

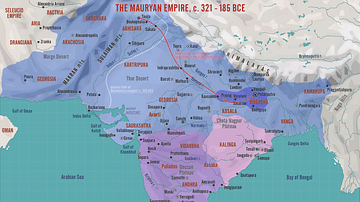

Kautilya (c. 4th century BCE) in his Arthashastra treats forts highly. For him, the fort was one of the seven constituents (saptanga) of a king's sovereignty, without which he could not call himself king – “the haven of the king and of his army is a strong fort” (Shamasastry, 426). The kingdom's treasury was safe in a fort, and it was from a fort that a king could successfully carry out his reign and keep enemies in check while augmenting his own strength. Virtually every kingdom possessed forts, including:

- the various dynasties ruling Magadha (6th-4th century BCE)

- Mauryas (4th-2nd century BCE)

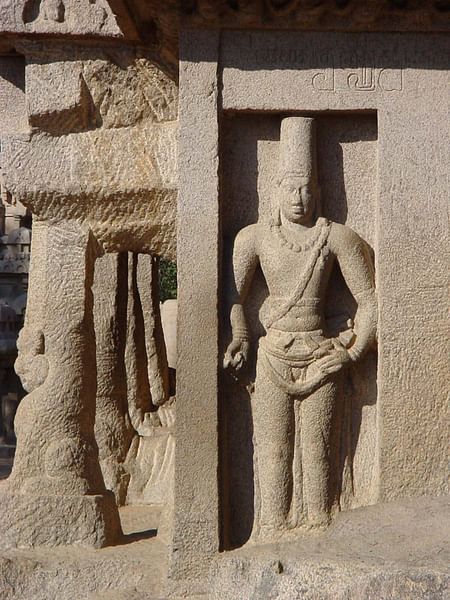

- Pallavas (3rd-9th century CE)

- Cholas (4th century BCE - 13th century CE)

- Rashtrakutas (8th-10th century CE)

- Chalukyas of Vatapi (6th-8th century CE)

- Western Chalukyas of Kalyani (10th-12th century CE)

The Magadhan king Ajatashatru (492 BCE - 460 BCE), while engaged in a war with Koshala, Vaishali, and their allies, anticipated an attack from them. The fortress of Pataligrama was built in defence, which within a generation developed into the city of Pataliputra, the capital of empires in India for centuries to come. Owing to the security they provided, forts were also treated as centres for administrative units. Kautilya mentions that a fortress called sthaniya should be erected at the centre of 800 villages. In the Sarnath Pillar Edict of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka (268 BCE – 232 BCE), there is a reference to a kota-vishava (Sanskrit: kotta-vishaya) or a 'district around a fort'.

CONSTRUCTION & TYPES OF FORTS

The ancient Indians considered it necessary to build forts in border regions as they were key to the kingdom's security and could stop invaders from reaching the capital. The Buddhist text Digha Nikaya mentions a border city defended by strong ramparts and towers and provided with a single gate. Book II of the Arthashastra mentions that forts should be constructed in the extremities of the kingdom, manned by boundary-guards (antapala). All the four quarters of a kingdom should be provided with defensive fortifications, as described here:

[Forts should be] constructed on grounds best fitted for the purpose: a water-fortification (audaka) such as an island in the midst of a river, or a plain surrounded by low ground; a mountainous fortification (parvata) such as a rocky tract or a cave; a desert (dhanvana) such as a wild tract devoid of water and overgrown with thicket growing in barren soil; or a forest fortification (vanadurga) full of wagtail (khajana), water and thickets. Of these, water and mountain fortifications are best suited to defend populous centres; and desert and forest fortifications are habitations in wilderness (atavisthanam).

(Shamasastry, 66-67)

This classification of forts was employed throughout the ancient period in India and many such forts, including hillforts and water-forts, were built by different dynasties at different points in time. In 543 CE, King Pulakeshin I (543 CE – 566 CE) made Vatapi (present-day Badami, Karnataka state) the capital of the Chalukya kingdom and built a fort on what is now known as the North Hill. This hillfort was fortified above and below. The Aihole Inscription of the Vatapi Chalukya king Pulakeshin II (609 CE – 642 CE) mentions the island fort of Revati and the land fort at Vanavasi.

The Buddhist text Anguttara Nikaya specifies seven requisites of a fortress, including a moat, and four kinds of supplies necessary for its maintenance. The Jataka tales also mention fortified cities complete with walls, ramparts, buttresses, watchtowers and massive gates. The Arthashastra in its Book II also contains detailed descriptions of the construction of a fort, which include:

- moats containing crocodiles

- ramparts, parapets, towers, turrets, and positions for archers (indrakosha)

- a passage for flight (pradhavitikam) and exit door (nishkuradvaram)

- twelve gates, with a secret land way and waterway

- the number and amount of resources necessary for withstanding long sieges, such as food and weaponry.

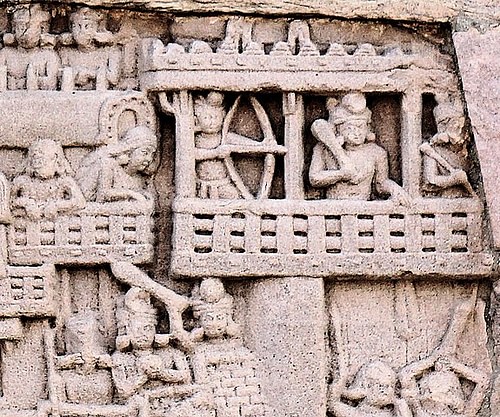

That such forts were actually constructed, whether in sum or part, can be seen from the early reliefs at Sanchi, Bharhut, Mathura, Amaravati, and Nagarjunikonda. They show the outer view of the city walls, preceded by a moat. The city walls have gatehouses and defensive towers. The walls themselves were made of brick or wood and often had re-entrant angles of which the salient corners had projecting bastions. The top of the walls ends in copings or battlements. The gatehouse is flanked by two lofty towers, each rising to several storeys. During the reign of Chandragupta Maurya (322-298 BCE), Pataliputra came to have an external wall with 570 towers and 64 gates. The ditch or moat was c. 182 m (600 feet) wide and c. 15 m deep.

By the time Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BCE) invaded India in 326 BCE, virtually the entire country was dotted with forts. Even small chiefs possessed them. Ancient historians such as Curtius (1st century CE) and Arrian (c. 86/89 – c. after 146/160 CE) give details of such fortifications. They also mention how Alexander had to contend against a number of forts such as Massaga, Sangala, Aornos, etc.

The accounts of Chinese and early Muslim travellers show that over time, not much change was witnessed in fort construction which continued to follow the pattern mentioned above. The only discernible change was an increase in the size of the outer walls and in the dimensions of the moats in order to increase security. Cities throughout India continued to be fortified, which in South India, besides Vatapi, included the Pandya capital Madura or Madurai (present-day Madurai, Tamil Nadu state) and the Pallava capital Kanchipuram (present-day Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu state) among others. Towns with thriving ports such as Vizhinjam (present-day Vizhinjam, Kerala state), were also heavily fortified. Being flourishing centres of commerce, they were often targeted by invaders as in the case of Vizhinjam which was routinely targeted by the Pandya and Chola kings from the 7th to 10th centuries CE.

Siege warfare & troops

The forts had permanently stationed garrisons with a proper division of their functions. The Buddhist Pali sources give a list of such officers and troops, which include:

- billeting officers (chalaka)

- soldiers of the supply corps (pindadayika)

- stormtroopers (pakkhandino)

- warriors in (leather) cuirasses (cammayodhino)

- dovarika or gatekeeper.

Members of the royal family including princes were expected to participate in the defence of forts as well as in the assault of enemy forts. The Anguttara Nikaya expressly mentions “the king's sons” as part of the garrison. That kings also participated in defence can be evidenced from the fact that Pulakeshin II died defending his capital Vatapi against the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I (630 CE – 655 CE) in 642 CE.

During the Mauryan period, the durgapala, or officer in charge of a fort, was held in high esteem. The senapati, or commander-in-chief, was expected to know how to assail a fort. The nagaraka, or officer in charge of a city, was to inspect on a daily basis the hidden passage for going out of the city as well as the forts, fort walls, and other defensive works.

Elephants were specifically taught to batter fort walls, and in the Arthashastra this training is called as nagarayanam. Troops of the Western Ganga kingdom (350 CE – 1024 CE), were specifically trained in assaulting hillforts. Whenever required, the garrison could be supported by the local people who would join in defending the fort. The attacking army, however, had to rely on its own strength. The best course was to bring in huge numbers to make the assault, as the Vatapi Chalukya kings often did.

Assault & defence

Since forts were constructed considering the geographical advantages provided by the site and the addition of protective features like walls, ramparts, etc., any strategy to reduce such strongholds had to keep all this in mind. The defenders would also take full advantage of the natural features as in the case of hillforts. The Pallava king Mahendravarman I (600 CE – 630 CE) forced Pulakeshin II to retreat before the walls of Kanchipuram, behind which he had hidden in face of the advancing Chalukya army.

Thus, owing to the challenge the forts presented, their capture was regarded as quite a feat. The Eastern Chalukya king Vishnuvardhana I (624 CE - 641 CE) was believed to have acquired the title Vishamasiddhi (Sanskrit: “one has attained success in difficult enterprises”) because of his great success (siddhi) in capturing all kinds of impregnable (vishama) fortresses on land and sea (sthala-jaladi-durga).

Regarding siege equipment, possibly, battering rams were used, but not much evidence is available here. However, the infantry while scaling the walls would have used ladders or ropes. When it came to assaulting city or fort walls, elephants were given a much more significant role. They are referred to as purabhettarah (town-breakers) in the Mahabharata. Book XIII of the Arthashastra covers in detail the means to capture a fort. It recommends sowing dissension among enemy ranks and the use of spies in weakening the enemy. Siege operations would begin when the enemy king was in a weakened state and low in supplies. The moats would be countered through various means. Many parts of the fort and houses within could be set on fire. This was suggested as a last resort by Kautilya as the fort and all the resources within should ideally be captured intact. However, captured forts were destroyed or burnt by the invaders.

Siege engines do not seem to be used often. The stress was on a general assault, made through by breaking open the gates after crossing the moat, or by inducing the enemy to come out for a sally. An assault was considered best at a time when the enemy was tired after fighting either on the walls or in an open battle and had thus lost many of its men, while the general public inside the fort would be generally distracted by celebrating festivals or religious rituals or engaging in drunken brawls or simply asleep. Weather conditions also determined the day of an assault. A cloudy day, or a day when there was a thick fog or snow, was seen as ideal.

Archers seem to have played a major role in both defence and assault. Defenders offered a good fight in many cases. One relief at the Sanchi stupa shows the Mallas defending their city of Kushinagara against a besieging army. This is a graphic description of how siege warfare was conducted in the pre-Mauryan and Mauryan times. This siege likely took place sometime in 5th century BCE. It shows the attackers amassing outside the city walls with all kinds of troops – elephants, chariots, infantry and cavalry – and appear to be surrounding the city. The multi-storeyed buildings of the city can be seen beyond the city walls, which are depicted as being tall and strong. Citizens, including women, are peering down at the attackers from their balconies. Defenders are actively engaging the enemy by throwing stones and shooting arrows, and some of them are ready with their clubs and swords to push down the besiegers climbing the walls. No siege equipment is shown, and the assault is being made by the infantry attacking the besieged. Some soldiers are shooting arrows, and others are climbing up the walls (the means used for climbing are not shown).

Legacy

The emphasis on fort building and siege warfare continued well into the medieval and early modern periods. Many of the ancient forts, if not destroyed by attackers, were developed further or revamped by medieval and later dynasties, especially the Rajputs, according to the needs of the times. Forts of different kinds, like hillforts, continued to be built. The nature of siege warfare eventually changed with the advent of gunpowder and artillery, and the techniques of defence and assault also changed. But even then, many of the forts held strong. They could withstand protracted sieges and on many occasions, gave a hard time to the attackers, which included troops of colonial European powers like the East India Company. Many of these forts are still standing today as a testament of the importance of forts and siege warfare in India, a process that had begun in the ancient times and provided the basis to later periods.