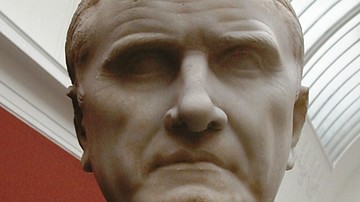

The Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE was one of the greatest military catastrophes in all of Roman history when a hero of the Spartacus campaign, Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 BCE), initiated an unprovoked invasion of Parthian territory (modern Iran). Most of the information concerning the battle and its aftermath comes from two major sources: the 1st-century CE historian Plutarch's biography of Crassus and Roman History by Cassius Dio (c. 155 - c. 235 CE).

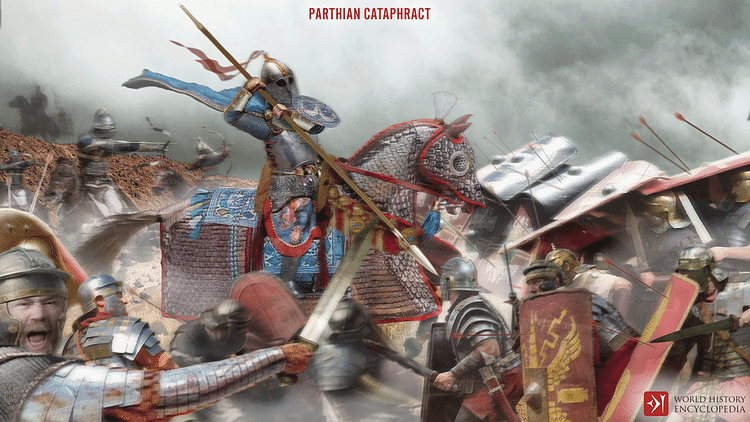

Carrhae proved to be a complete disaster from its beginning. Not only were the Romans not used to fighting on the open terrain and in the unbearable heat of Syria but they also had never seen anything like the Parthian cavalry: the cataphracts or armored camels. Iain Dickie, in his article on the battle in Battles of the Ancient World states that Crassus attempted "to score one over his political rivals Pompey and Caesar. He hoped for glory and riches but got tragedy and death" (140). In the end, 20,000 Romans were killed, 10,000 were captured, and only about 5,000 escaped the carnage.

Crassus & the Triumvirate

Marcus Licinius Crassus was not the inept commander that the outcome of the battle exhibits. He had been a capable military leader as well as a successful statesman. Along with Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) and Pompey the Great (106-48 BCE), Crassus formed the First Triumvirate that effectively ruled the Roman Republic from 60 to 53 BCE. An unstable Republic and a near civil war led these three men to set aside their differences and even disdain for one another to join forces and for nearly a decade dominate the Roman government, even controlling elections.

With Caesar's success in Gaul and Pompey's victories against pirates in the Mediterranean Sea, Crassus needed a military conquest to advance his personal and family's political position in Rome. Already one of the richest men in Rome and the money behind the triumvirate, Crassus eyed the east and Parthia in particular. He dreamt of Roman supremacy there and an opportunity for glory. Unfortunately for him, little was known of Parthia except that it was considered extremely wealthy. Other eastern states had been easily captured, so why not Parthia? Although Pompey had signed treaties with the Parthians, Crassus chose to ignore them. This arrogance and greed would spell his eventual doom as well as the demise of the First Triumvirate.

Campaign Against Parthia

Leaving Rome in November 55 BCE Crassus marched eastward into Asia Minor eventually crossing the Euphrates River and arriving in Parthian territory. Along the way, he looted both towns and temples, increasing his personal wealth. Crassus left 7,000 cavalry and 1,000 infantry to garrison these captured towns. Spending the winter in Syria, he waited for his son Publius and his Gallic cavalry to arrive. In the end, his army consisted of 28,000 infantry, 4,000 light infantry, 1,000 Gallic cavalry, 3,000 Roman cavalry, and 6,000 Arab cavalry. Unfortunately for Crassus, the Arab cavalry would depart before the fighting began. As he waited for the weather to clear, he was met by Parthian envoys inquiring of Rome's purpose and demanding his withdrawal. Was his presence official? Crassus informed them that it was, indeed, official.

Despite advice from the Armenians who knew the region much better, of course, Crassus and his army marched eastward into Seleucia. The Parthian king Orodes II (r. 57-37 BCE), who had recently defeated the Armenians, led an army into Armenia to prevent them from joining Crassus. Meanwhile, the Parthian regional governor Surena gathered his forces to oppose the Romans. When news arrived that the Parthians were preparing for battle, Crassus quickly organized his men. At first, he formed them into a long line but then, realizing that his flanks would be vulnerable, he re-formed them into a tight square. Each side of the square contained roughly 5,700 infantry or 12 cohorts. Inside the hollow square were not only the light infantry and cavalry but also the baggage and camp followers. Plutarch wrote of Crassus' trepidation:

All were greatly disturbed, of course, but Crassus was altogether frightened out of his senses, and began to draw up his forces in haste and with no great consistency. At first, as Cassius recommended, he extended the line of his men-at-arms as far as possible along the plain, with little depth, to prevent the enemy from surrounding them, and divided all his cavalry between the two wings. Then he changed his mind and concentrated his men, forming them in a hollow square of four fronts, with twelve cohorts on each side. (ch. 25)

Legions vs. Cavalry

The Romans had never encountered anything like the highly skilled Parthian cavalry who were specifically trained to fight on open terrain. First of all, unlike the Roman and Greek armies, there was no Parthian infantry only the infamous lance-carrying cataphracts of armored camels (about 1,000 in total) and lightly-armored mounted archers (around 10,000). They were swift-moving and rapid-firing. They emphasized mobility and expert horsemanship with quick charges and feigned retreats. Lastly, there was the famed Parthian shot when a mounted archer would ride away at full speed from his enemy and, while spinning around in his saddle, he would shoot a barrage of arrows over his horse's rump. The tactic proved almost impossible to counter, and the Parthian arrows could penetrate Roman armor while the lancers even had the capability of impaling two soldiers at once.

On the Roman side of the battle, there was the famed legionary, a soldier proven to be far more adaptable in hand-to-hand combat. He had already proven this against the Greeks. The average legionary was armed with a pilum (a heavy javelin) and a gladius Hispaniensis (a short stabbing sword). He wore a bronze helmet, shield, and mail tunic. He also had to carry entrenching tools, a bedroll, a cloak, cooking utensils, and rations. None of these would help him against the Parthians. His lack of the necessary training and inability to fight in the emptiness of the Syrian Desert would put him at a distinct disadvantage.

Battle

The Romans, still neatly arranged in their tight square, waited for a direct Parthian charge that never came. Plutarch wrote that the sound of the Parthians on the battlefield confounded one's soul:

For the Parthians do not incite themselves to battle with horns or trumpets, but they have hollow drums of distended hide, covered with bronze bells, and on these they beat all at one in many quarters, and the instruments give forth a low and dismal tone. (ibid)

Parthian tactics were simple: a continuous volume of fire. The archer-cavalry would ride around the square rapidly firing arrows into the Roman center. Any attempted counterattack failed. Plutarch said,

…when Crassus ordered his light-armed troops to make a charge, they did not advance far, but encountering a multitude of arrows, abandoned their undertaking and ran back for shelter among the men-at-arms, among whom they caused the beginning of disorder and fear, for these now saw the velocity and force of the arrows, which fractured armor, and tore their way through every covering alike, whether hard or soft. (ibid)

The Parthian cavalry could not be stopped, and Crassus realized he had to make a move. Plutarch wrote how the Romans had hoped the Parthians would eventually run out of arrows until they saw the camels heavily loaded with what appeared to be a never-ending supply.

…when they perceived that many camels laden with arrows were at chose quarters, from which the Parthians … took a fresh supply, then Crassus, seeing no end to this, began to lose heart, and sent messengers to his son with orders to force an engagement with the enemy… (Plutarch, ibid)

Crassus ordered Publius to lead his Gallic cavalry of 1,000, who were already suffering from the extreme summer heat, 300 additional cavalry, 500 foot archers and eight cohorts of legionnaires to counter the intense Parthian attack.

Death of Publius

Following the retreating horse archers, Publius was some distance from the square when the Parthians stopped and turned around. The Romans immediately halted, thereby becoming easy targets for the Parthian archers. Plutarch remarked that Publius had truly believed he was victorious in his pursuit of the Parthians until he realized that he had been tricked: "[the] struggle was an unequal one both offensively and defensively, for his [Publius'] thrusting was done with small and feeble spears against breastplates of rawhide and steel…" (Plutarch, ch. 25)

Of Publius' death, Cassius Dio wrote:

When this had taken place, the Roman infantry did not turn back, but valiantly joined the battle with the Parthians to avenge his death. Yet they accomplished nothing worthy of themselves because of the enemy's numbers and tactics… (441)

Of the 5,500 Romans, 500 were captured while the rest were riddled with arrows. Publius' head was carried on a pike in the next assault the cataphracts made on the Roman square. Plutarch wrote of the effect this had on the Romans:

This spectacle shattered and unstrung the spirits of the Romans more than all the rest of their terrible experiences, and they were all filled, not with a passion for revenge, as was to have been expected, but with shuddering and trembling. (ch. 26)

The Parthians 'scornfully' inquired of Publius' family, adding that the cowardly Crassus could not be the father of a son of such noble and splendid valor. However, despite their disdain, they did grant Crassus a peaceful evening to mourn his son.

Being ill-equipped for nighttime defense and fearing a Roman assault, the Parthians chose not to continue their attack, instead they made camp far from the Romans. Plutarch wrote that it was a troubling night for the Romans, for they could not bury their dead or care for the wounded. Despite this, that night 300 Romans under a commander named Ignatius made their escape to Carrhae, informed the city of the battle, and then moved on. Plutarch wrote:

Ignatius hailed the sentinels on the walls in the Roman tongue, and when they answered, ordered them to tell Coponius, their commander, that there had been a great battle between Crassus and the Parthians. Then, without another word, and without even telling who he was, he rode off to Zeugma. He saved himself and his men, but got a bad name for deserting his general. (ch. 27)

Retreat to Carrhae

Crassus realized that staying was hopeless and he must escape. Leaving the wounded behind, the remainder of the Roman army made their way to the safety of Carrhae, although four cohorts became lost in the night. Crassus understood that he would not be able to remain very long in the city and was already planning to move on.

The following morning the Parthians arrived at the Roman camp, slaughtered the 4,000 wounded and abandoned soldiers, found and wiped out the missing four cohorts, and then continued on to Carrhae. At the city walls, the Parthians demanded that Crassus and his second-in-command Cassius be surrendered in chains. According to Plutarch, Surena did not want to lose the 'fruits of his victory,' so he sent a messenger who spoke 'the Roman tongue' to ask for either Crassus or Cassius to meet and have a conference. With limited supplies in the town and a discouraged army, Crassus, not wishing to meet with Surena, saw it was essential to leave the city. In the end, the attempted escape would prove disastrous.

That night Crassus and his army made a failed attempt to flee to Armenia only to return to Carrhae where they became lost in a marsh. Cassius Dio wrote:

For Crassus, in his discouragement, believed he could not hold out safely even in the city any longer, but planned flight at once. And since it was impossible for him to go out by day without being detected, he undertook to escape by night, but failed to secure secrecy, being betrayed by the moon, which was at its full. (441)

Waiting for a moonless night, they again left in darkness but became confused in unfamiliar terrain and became lost. Unfortunately, Crassus had trusted the wrong man to lead him and his men to safety: the traitor Andromachus.

But since it is not the custom, and so not easy, for the Parthians to fight by night, and since Crassus set out by night, Andromachus, by leading the fugitives now by one route and now by another, contrived that the pursuers should not be left far behind, and finally he diverted the march into deep marshes and regions full of ditches, thus making it difficult and circuitous for those who still followed him. (Plutarch, ch. 29)

The Romans took refuge on a large hill. Meanwhile, the Roman commander Octavius made an escape with 5,000 men to Sinnaca, later returning to help drive off the Parthians only to meet his own death at the hands of a Parthian soldier. Finally, terms were again offered. Crassus was reluctant but his men urged him on "…abusing and reviling him for putting them forward to fight men with whom he himself had not the courage to confer even when they came unarmed" (Plutarch, ch. 30).

The results of the meeting and the death of Crassus and Octavius are a matter of conjecture and myth. Supposedly, Surena asked for terms that called for the Romans to abandon all territory east of the Euphrates. Crassus, according to Cassius Dio, was fearful. The meeting did not go as planned, for Crassus would meet his death. Plutarch remarked, "… the Parthians came and said that as for Crassus, he had met with his deserts, but that Surena ordered the rest of the Romans to come down without fear" (ch. 31). Some complied while others tried to escape only to be captured and 'cut to pieces'.

Cassius Dio wrote that Crassus was slain "…either by one of his own men to prevent his capture alive or by the enemy because he was badly wounded" (445). Another story claims that the Parthians poured molten gold into his mouth 'in mockery' of his vast wealth. Crassus' head was sent to the Parthian king where it was used as a prop in a performance of Euripides' play The Bacchae - it became the head of the tragic Pentheus who had been decapitated by his mother.

Aftermath

At Carrhae Crassus' greed and ambition blinded him to the realities of war in the east. Previously, Crassus had had success as a military commander, but Carrhae showed the failure of his normally capable ability to execute a rational plan. It has been suggested that he may have suffered from PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). Certainly, he seems to have exhibited anger, a lack of concentration, alienation, and depression, especially after the death of his son when he refused to leave his tent.

With the death of Crassus, the triumvirate was doomed. Crassus had been the glue, and soon Caesar and Pompey were at odds - it would finally end with the death of Pompey. Supposedly, as a self-proclaimed dictator-for-life, Julius Caesar had hoped to lead his army eastward to avenge Crassus' death and get back the lost eagle standards of the fallen legions, but his death on the Ides of March 44 BCE would spell the end of any such planned reprisal.

While Rome would occasionally penetrate into Parthian territory - Emperors Trajan and Septimius Severus made progress - war with Parthia never materialized. Parthia proved to be far more defensive than aggressive. The area would always remain a thorn in the side of the empire. However, despite the catastrophic losses at Carrhae, Rome was able to survive, continue to conquer and emerge as an empire. The Battle of Carrhae, along with the battles at Cannae (216 BCE) and Adrianople (378 CE), remain among the worst military disasters in Roman history.