The English word 'veterinarian' as defining one who provides medical care to animals, comes from the Latin verb veheri meaning “to draw” (as in "pull") and was first applied to those who cared for “any animal that works with a yoke” – cattle or horses – in ancient Rome (Guthrie, 1).

The association of the term “veterinary medicine” with Rome has encouraged a tendency to begin any discussion of the history of the practice either with the Roman physician Galen (l. 129-216 CE), the earlier Greek “Father of Medicine” Hippocrates (l. c. 460 - c. 379 BCE), or the writer Vegetius (l. late 4th or 5th century CE) when, in fact, the practice was already well-established by the time they lived.

What is possible, however, is to chart a rough evolution of veterinary practice in ancient civilizations such as China, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India long before it arrived in Greece and Rome from whence it would later be developed throughout Europe.

It is almost a certainty that physicians of Asia and the Near East were practicing veterinary medicine long before the written records which attest to such practice were created, but the accounts which do exist make it clear that the Greek and Roman writers frequently associated with the epithet “Father of Veterinary Medicine” actually only contributed to what had already been established.

Enlightenment writers of the 18th century CE had no knowledge of contributions to the field prior to the Greeks and Romans and so, naturally, began their treatments of the subject with those civilizations; scholarship since then has made it clear that writers such as Hippocrates and Vegetius were later contributors, not pioneers, in veterinary medicine.

Chinese Mythological Origin & Practice

As noted, it is not possible to definitively state where veterinary medicine was first practiced but the earliest documented evidence comes from China. One of the most popular myths of ancient China concerns the god Fuxi (also given as Fu-Hsi, Fu-Shi) and his sister-wife Nuwa who created humanity and bestowed upon them the gifts of civilization. Fuxi is known as “the ox-tamer” for his gift of domesticating animals and clear evidence of domestication was already long established by the time Banpo Village was thriving between 4500-3750 BCE.

After domesticating animals, Fuxi is said to have taught humans how to care for them. The earliest examples of veterinary medicine in China have to do with the care of cattle and horses. Doctors known as “horse priests” used acupuncture to successfully treat lame or colic horses c. 3000 BCE. Veterinary practice developed from that point to include other animals and the use of medicinal herbs, incantations, and various procedures in the treatment of illness and injury.

Mesopotamian Practice

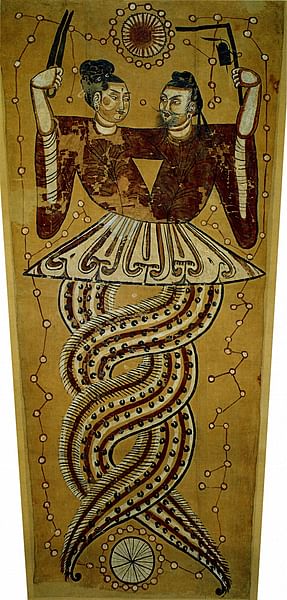

In Mesopotamia, veterinarians were also already established by 3000 BCE and the practice was also associated with the divine. The goddess of health and healing was Gula (also given as Ninkarrak and Ninisinna, closely associated with dogs and their protective/healing aspects) who instituted the art of medicine with her consort Pabilsag, her sons Damu and Ninazu, and her daughter Gunurra. Of her children, the most influential was Ninazu – associated with serpents (symbols of transformation), healing, and the underworld – whose symbol was the staff of intertwining serpents, later associated with Hippocrates and, today, the symbol of the medical profession.

The first veterinarian known by name is the Sumerian doctor Urlugaledinna who served under Ur-Ningirsu (r. 2121-2118 BCE), king of Lagash, son and successor of the great king Gudea (r. 2141-2122 BCE). According to Dr. Saadi F. Al-Samarrai:

[Urlugaledinna] gave a particular attention to an apparatus consisting of two metal handles attached to two twisted cords with two shafts or lamina which bend upwards at their tips representing a kind of forceps used by Sumerian obstetricians in difficult live births. It proves also that surgical instruments were used for opening abscesses and other minor surgical operations [along with] needles and threads for suturing. (129)

Urlugaledinna's cylinder seal – essentially his personal identification – shows this pair of tongs along with Ninazu's staff of the intertwined serpents and he is more closely associated with veterinarian practice than work with humans though no details as to how his practice developed are available. This is fairly common in Mesopotamian texts which often take for granted an audience's knowledge of the subject. As the Orientalist Samuel Noah Kramer points out:

There were also veterinarians known as “the doctor of the oxen” or “the doctor of the donkeys”; but they are only mentioned in the lexical texts and nothing else is known about them as yet. (Sumerians, 99)

Whatever these early veterinarians did, they had established their practices well enough to be able to define animal-related disease and treatment by the time the law code of Eshnunna was written c. 1930 BCE. The Code of Eshnunna identifies rabies, its effects, and sets the fine to be paid by the owner of a rabid dog who bites someone. The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BCE) recognizes veterinarians as a separate class of medical doctor and sets the fees they are to be paid; clearly establishing veterinary care as a respectable profession.

Egyptian Codification

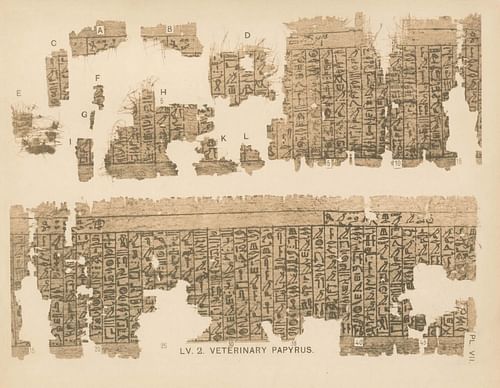

By the time the Code of Hammurabi was engraved at Babylon, veterinarians in Egypt were already long recognized for their skill and had already produced a work on veterinary science, known today as the Kahun Papyri. Dated to the period of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE), and specifically to the reign of Amenemhat III (c. 1860 - c. 1814 BCE), the Kahun Papyri contains texts on a number of different subjects ranging from festivals to be held to gynecological issues and treatments, to veterinary practice and diagnoses of illness.

Scholar Conni Lord notes how, “as an agricultural society, humans and animals in ancient Egypt would have regularly shared the same space, often to the detriment of each other” (141). This close contact would have necessitated a human response to animal disease in any culture, prompted simply by the instinct of self-preservation, but would have been acted on earlier and more proactively by the Egyptians with their high regard for animals. Some scholars, in fact, have argued that veterinarian practice in Egypt is among the earliest in the world, dating back at least to the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) if not earlier. Lord comments:

Animals, like their human carers, would have displayed a high incidence of parasitic disease while the harsh glare of the Egyptian sun and frequent dust storms must have led to a high occurrence of both human and animal eye disease. The environmental conditions of ancient Egypt would have facilitated animal and human disease patterns. (142)

Among these diseases was African Trypanosomiasis and, especially, nagana (animal trypanosomiasis) which was spread by the bite of the tsetse fly. Infected flies which bit animals would then spread the disease to humans, causing the “sleeping sickness” which, if left untreated, eventually led to death.

The Kahun Papyrus specifically deals with nagana (given as ushau in the text), prescribes remedies, and specifically mentions the importance of washing one's hands before, during, and after treating an infected animal. The Kahun text deals primarily with the treatment of cattle but birds, dogs, and fish – all three kept as pets – are also mentioned.

Indian Advances

Whether Egyptian veterinary science traveled to India or developed there independently is unknown but by the time of the Vedic Period (c. 1500-500 BCE), veterinarians were an established and respected profession in the region. According to scholar R. Somvanshi:

It is believed that the religious priests, who had the responsibility of maintaining cattle, were the first animal healers or veterinarians. A number of Vedic hymns indicate medicinal values of the herbs and it is likely these priests were also apt to [use] their medical knowledge to keep cattle free from ailments. (3)

Animals received good medical care in ancient India. Physicians treating human beings were also trained in the care of animals. Indian medical treatises like Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, and Harita Samhita contain chapters or references about care of diseased as well as healthy animals. There were, however, physicians who specialized only in the care of animals or in one class of animals only; the greatest of them was Shalihotra, first known veterinarian of the world and the father of Indian veterinarian sciences. (5)

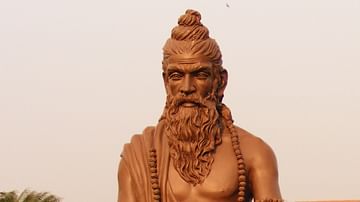

Shalihotra (l. c. 3rd century BCE) was a physician who dedicated himself solely to the care of animals. His work, the Shalihotra Samhita, dealing with veterinary science, is based on Sushruta's earlier work on human anatomy, physiology, and surgical techniques; these were adapted for the care of animals. By the time of the great king Ashoka (r. c. 268 - c. 232 BCE), the first veterinary hospital in the world was established in India with its underlying vision based on the work of Shalihotra.

Greek & Roman Developments

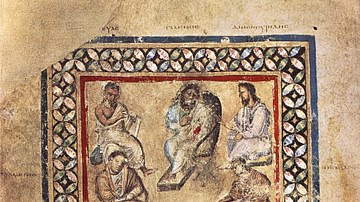

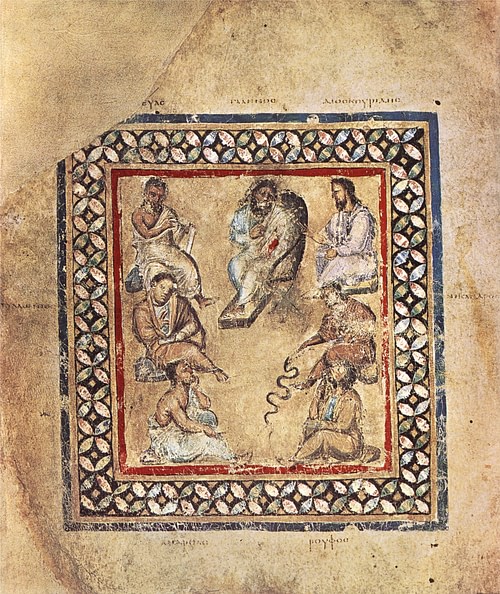

The Greeks follow the same paradigm as other civilizations in, no doubt, developing some form of veterinary science shortly after the domestication of animals but one of the most comprehensive treatments of the subject comes from Hippocrates who emphasized a completely empirical approach to diagnosing and treating both humans and animals.

Hippocrates was the first Greek healer to maintain that illness was caused by environmental factors, diet, and lifestyle and was not a punishment from the gods nor an infliction caused by evil spirits or the restless dead. He was not, however, the first in history to make this claim as it was suggested much earlier by the Egyptian polymath Imhotep (l. c. 2667-2600 BCE) and later by Sushruta and Shalihotra in India.

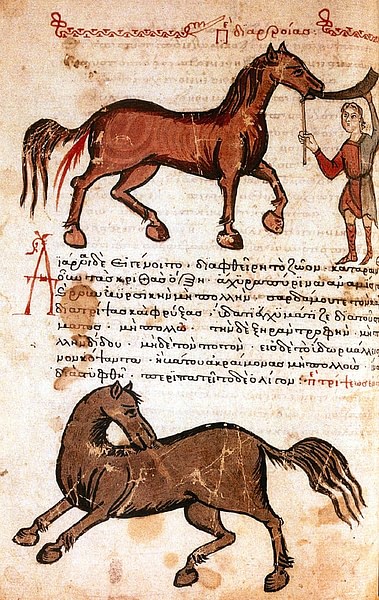

Hippocrates suggested diet as one of the most important aspects of maintaining health, in humans or animals, as well as regular exercise, sunlight, massage, relaxation, and elevation of one's mood, aromatherapy, and regular baths. Although his work focused on human health, it also extended to the welfare of animals. By 130 BCE, a man named Metrodorus of Lamia (in Thessaly) was famous for his skill in healing animals based on Hippocrates' work. He was especially known for his work with horses and was well respected as a veterinary surgeon.

There is no doubt that Greek medical practices were adopted by the Romans and, most famously, by Galen who recognized the similarity in human and animal physiology. He was able to treat his patients as well as he did through his knowledge of anatomy derived from his work with animals. He correctly assumed that what was harmful to an animal would be equally so to a human and, conversely, what would encourage health in the one would most likely do so in the other.

He had clearly read Hippocrates as he insisted on the same basic understanding a veterinarian should have, prior to treating a patient, that disease was naturally occurring and was not caused by divine or supernatural influences. His work has led many through the centuries to consider him, often above other Roman or Greek writers, as the “Father of Veterinary Medicine” for the scope of his work and its influence on the development of veterinary science.

Conclusion

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, and the rise of Christianity, prior knowledge of veterinary science was lost. Dr. Earl Guthrie comments:

The Church forbade dissection and autopsies and confiscated and destroyed much of the literature on the subject of Veterinary Medicine. During this time no new literature was written. The only work that was done was by the Arabs in Spain. Because of their love of the horse and excellent horsemanship, they were interested in the diseases of the horse. (6)

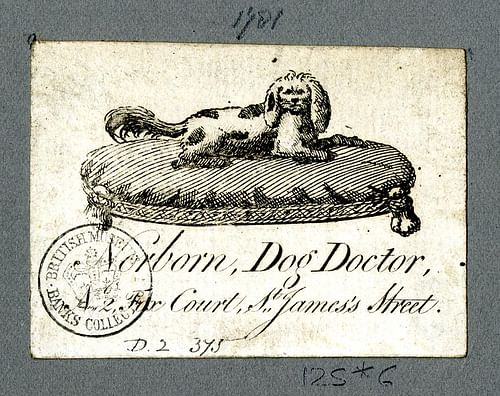

The lack of interest in veterinary medicine stemmed from the medieval Church's insistence that animals had no immortal soul and so were not worthy of medical treatment. If one's pet cat or dog died, according to the view of the Church, it was of as little consequence as the death of a fly or flea. It was not until the late 12th and early 13th centuries that Europeans began to again pay attention to the health of animals as it affected human wellbeing. Even so, this interest was primarily focused on the health of horses and cattle, the one used in warfare and for transport, and the other for food and agricultural endeavors. The health of an animal for its own sake would not become a focus until much later.

It was not until the Age of Enlightenment (c. 1715-1789) that veterinary medicine would again be regarded with any serious interest. Those who wrote on the subject, however, had no knowledge of the contributions of the Chinese, Sumerians, Indians, Egyptians, or others and believed the works of the Greeks and Romans to be the earliest in the field. It was natural, therefore, that Hippocrates, Galen, and Vegetius should be the ones whose work informed the first veterinary schools of Europe.

Bourgelat is sometimes cited as the “Father of Veterinary Medicine” for founding his school but this claim, still appearing in the present day, ignores the establishment of the veterinary college in India under Ashoka and the work of the Egyptian physicians who created the Kahun text. The most recent “Father of Veterinary Medicine” is the well-known American physician James Harlan Steele (l. 1913-2013) who is, justly, hailed for elevating public awareness of the care and safety of animals.

Although Dr. Steele's accomplishments in the field are admirable, he – like other Western physicians before him referenced as “firsts” in the discipline – is by no means the first. The actual “Father of Veterinary Medicine” – or “mother” for that matter – may never be known but the practice has a much longer, and grander, history than is generally assumed.