The Hidatsa Sun Dance Ritual (also known as Hidatsa Sun Dance) is a Native American story of the Hidatsa nation illustrating the practice of an individual initiating the Sun Dance for personal reasons, in this case, to win the hand of the chief's daughter in marriage. The narrative has become significant in preserving the details of the Sun Dance.

The Hidatsa were a Siouan people, related to the Sioux by language but with their own culture and traditions. The Sun Dance, a ritual observed by many nations of the Plains Indians of the regions now known as Canada and the United States, is a ceremony enacted to awaken the Earth after winter and give thanks for the gifts of life, including the sun, that come from Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit or Great Mystery. Each nation has its own version of the Sun Dance, though the basic form follows the same model, and Hidatsa Sun Dance Ritual describes one such variation.

In any nation, an individual could call for a Sun Dance after either receiving a vision or in recognition of a personal or communal need. Even if the Sun Dance were initiated from some personal motive, it was still understood as beneficial to the entire community. In this story, the young man calls for the Sun Dance to prove himself worthy of marriage to the chief's daughter but, as the conclusion makes clear, the entire tribe is blessed through the ritual.

The Sun Dance & Story's Elements

The Sun Dance is one of the seven sacred rites of the Lakota Sioux, and the Sioux version of the ritual has become the best known, but almost all the Plains Indians Nations observed the ritual in giving back to the Earth, and the Creator, as well as awakening the Earth after the sleep of winter. Through the self-sacrifice of the participants in the ritual, the gifts of the Earth and the spirit world were acknowledged, but, further, visions were granted by the spirits, one's ancestors, or by Wakan Tanka, which provided individual and communal direction. The ritual's focus on gratitude for the many gifts received encouraged balance and harmony in that one was giving back out of the resources that had been given.

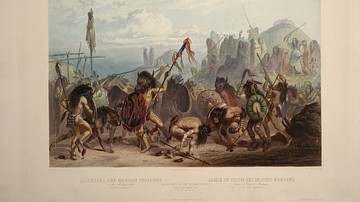

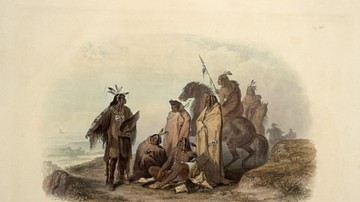

According to some scholars, the Sun Dance may have originated from the Okeepa Ceremony of the Mandan Nation as described by the artist George Catlin (l. 1796-1872) in the 1830s. The Okeepa Ceremony shares several similarities with the Sun Dance and may have been observed earlier (though this is unclear). It is equally possible that both rituals developed from an even earlier observance or that the Okeepa Ceremony described by Catlin, like the Hidatsa ritual, was simply a tribal variation on the commonly observed Plains Indians Sun Dance.

As with all sacred rites, the ceremonial pipe (chanunpa) and sacred tobacco (lela wakan = "very sacred") are central to the observance; the smoke is understood to carry the prayers of the people to the spirit realm. The smoke is not inhaled into the lungs but only held in the mouth and then released with one's prayers. In the Hidatsa story, the young man goes to a "medicine man" (here given as "priest") and offers him a pipe as a sign of respect in asking him to preside over the ritual. In accepting the pipe, the medicine man enters into a binding agreement with the young man which cannot be broken as the pipe and tobacco are considered sacred, and it would be unthinkable to break a contract or go back on a deal once sealed through the sharing of the pipe.

The "medicine man" is so-called from the concept of spiritual power translated as "medicine." Holy people of a community would be referred to as "medicine men" or "medicine women", owing to their resonant spiritual energies which enabled them to heal, predict the future, interpret visions, provide wise counsel, officiate at ceremonies, preserve the past through stories, and serve the community in similar ways.

These people would carry a sacred bundle – also known as a "medicine bundle" – containing items of spiritual power – but anyone could carry such a bundle. In the following story, the participants are shown entering the lodge, placing their medicine bundles on buffalo skins, and then hanging them from sticks. This is done so that the medicine bundle does not touch the ground as a sign of respect for the items it holds.

The sacred lodge mentioned in the story is a temporary structure built specifically for a given Sun Dance. Once the dance is announced, the entire community becomes involved in preparing for it. A tree is cut down to serve as the central pole and the ceremonial lodge is constructed of 28 surrounding poles which are then covered, sometimes, as in the Hidatsa story, leaving a hole open at the top through which the participants will gaze up through at the sun. The lodge is carefully, and prayerfully, constructed to represent the universe with each of the poles representing some specific power, from the Great Spirit to Mother Earth, the Four Winds, buffalo, and other natural and supernatural elements.

Once the lodge is prepared, and the participants have purified themselves, learned the sacred songs, fasted, and prayed, the ceremony begins. The Sun Dance, usually observed in June, lasts at least four days (though it can go longer) and concludes with a feast of thanksgiving. Afterwards, the lodge is dismantled, leaving only the center pole as a reminder of the event.

Text

The following story is taken from Voices of the Winds: Native American Legends by Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark. In the second paragraph, the young man clarifies his reasons for calling for a Sun Dance, and these represent the universal aspects of any Sun Dance in that they have to do with the communal good as much, if not more, than satisfying one's personal desires. In Native American culture generally, the good of the many is understood as more important than the good of the individual, and this recognition is central to the observance of the Sun Dance.

For many moons this particular Dancer had dreamed of the Chief's daughter becoming his wife. He had a vision of himself performing the Sun Dance in supplication for his secret wish. The vision prompted him to call his tribe together for a Sun Dance. Then the Dancer went to a high place alone, declaring to the Sun-God:

"In the coming summer, I shall build your lodge. I shall stand in the holy place. I shall kill buffalo and take the hides for you. I shall dance for you to be worthy of my beloved that I may have her for my wife. I shall dance for you so that I may have visions to help protect me from my enemies, so that my people may grow strong, so that no disease may come, so that the buffalo may be plentiful, so there will be an abundance of rain throughout the year."

The young Dancer called upon his Mother and his Grandmother saying, "Please tell all of your relatives that I shall perform the Sun Dance." They spread the news and the tribal men gathered buffalo hides. These they brought to the tribal women for curing. The Dancer provided the feasts for all who came to the celebration of his Sun Dance.

When everything was in readiness, the Dancer took a buffalo robe to the Priest, one of his Father's clansmen who was experienced in presiding over the Sun Dance Ceremony. The Priest represented the Sun-God. Before him the Dancer placed his buffalo robe and offered his pipe, saying, "Wise One, I have come to you for guidance. I wish to obtain the blessings of the Sun-God."

The Priest accepted the pipe and replied, "I am glad, my son, that you have come to me. I will aid you in this ceremony."

When the public announcement was made that the Sun Dance was to be given, the clansmen of the Dancer's Father asked for a scalp and left hand taken from an enemy. Sometimes both of these items were offered freely by a relative or purchased for a high price.

Before raising the sun-pole, a fresh buffalo head with a broad center strip of the back hide and tail were fastened with strong thongs to the top crotch of the sun-pole. Then the pole was raised and set firmly in the ground, with the buffalo head facing toward the setting-sun.

The sacred lodge was built by the Dancer and his clansmen. Men who owned medicine bundles brought them into the lodge of the Priest. The Dancer furnished each man with a buffalo robe upon which to lay his sacred bundle. The Dancer selected a favorite bundle that might be a red fox skin, for example, and for which the owner might ask the Dancer for a token.

The tribal Singer took the red fox skin and held it toward the burning incense. Then he touched it to the body of the Dancer and to that of his mother and Grandmother. Then he replaced it in front of its former owner. In this manner, the Dancer bought many of the medicine bundles and paid what the owners asked, in addition to his gifts of buffalo robes upon which rests each medicine bundle.

By this time, the Singer had learned the sacred songs and the manner of painting that each medicine required. The Singer taught the Dancer the secrets of each medicine that the Dancer bought. Some protect against enemies, some are good luck in contests, and some are for success in love and in hunting. When the Dancer had bought what he desired, the men went out, carrying his gift of the buffalo robe.

After construction of the Sun-Lodge, the Priest took the enemy scalp and left hand and raised them to the North Wind, South Wind, East Wind, and West Wind, saying, "I have often taken these in combat. May you have protection against your enemy always," giving them to the Dancer.

Young men, who are the Fasters and have their flesh pierced, arrived and went into the Sun-Lodge. Each carried his medicine bundle and an armful of sage. They crossed to the south side of the lodge, and each chose a place for his sage. They hung their medicine bundles on short sticks stuck in the ground in front of their sage.

The Dancer took the bundles that he brought and piled them on a buffalo skull. The Singer began the chants of mystery in a slow measured rhythm. The incense was then burned. The Dancer trembled from excitement. The Priest took white paint, holding it in the incense smoke for a moment and smeared it over the body of the Dancer and drew a white circle around his face.

To complete dressing the Dancer, the Priest hung a medicine hoop on his back, held by a cord around his neck. On his head, the Priest placed a band of jackrabbit skin, with the head dropping over his left ear. An eagle-down feather was tied to the Dancer's scalp lock, pointing backward. A whistle made of eagle-bone was hung around the Dancer's neck.

Meanwhile, the Fasters opened their medicine bundles, burned incense, painted themselves, and adorned themselves as they were taught by their elders and Guardian Spirits. Those having no medicine smeared themselves completely with white paint. Each Faster had an eagle-bone whistle hung from his neck and carried a shield and a lance.

The Singer painted himself and placed raven feathers in his hair. He arranged himself in front of the buffalo skin suspended from the sun-pole. He extended his arms toward it, rubbing his body as if receiving some special power from the buffalo.

Medicine-men arranged themselves south of the entrance to the Sun-Lodge. The old women of the tribe who prepared the spot for the Sun Dance, together with the medicine-women, sat on the north side. All come to pray and to fast. The relatives of the young male Fasters entered, carrying food. Each Faster took a bowlful of the food to a clansman of his father.

Then came the challenge to the Fasters' bravery. They approached the Priest and the Singer. Two small slits were cut in the shoulder skin of each young man presenting himself. Through the slotted skin, a leather thong was threaded with a wooden pin attached to the end preventing the thong from pulling out of the slotted skin.

The other ends of these thongs were attached to the top of the sun-pole (similar to a Maypole). The Priest and Singer twirled each Faster four times, his feet barely touching the ground. Then the Faster swung free twisting and circling around the sun-pole. But he dared not touch the thong with his hands. Any attempt to break the taboos was frowned upon by all his people as a lack of courage and endurance.

When the Faster finally broke loose from the sun-pole, he fell to the ground. Priest and Singer placed him gently on his bed of healing sage. There he remained and fasted from two to four days.

Any Dancer must first have been a Faster in an earlier Sun Dance. The Dancer danced back and forth continuously toward the sun-pole in the circle as long as a Faster was attached to the sun-pole. The Dancer sprang from the ground with his legs rigid and his feet together, his eyes fixed upon the buffalo head, and blew his eagle-bone whistle in rhythm with the beating drum.

The Dancer's mind was intent upon his desire to win his secret wish, the Chief's daughter, and to become a strong leader of his tribe. During his dance he prayed silently for those visions. He continued his dance until he fell from exhaustion. There he stayed until his visions appeared, or until the fourth day of the fast, if necessary.

The young Fasters lay upon their beds of sage. They have dreams and visions, which they related to the Priest. If they were sufficient, the Faster left the Sun-Lodge, because his supplications were answered by the Sun-God.

Near the doorway, the medicine-men still fasted and sought visions. Some of the younger boys of the tribe dragged buffalo heads through the village for fun.

If it was seen that a Faster cannot break away from the sun-pole and might be in danger, he was cut loose honorably. At the end of the fourth day, only a few Fasters still seeking visions remained.

The exhausted Dancer was taken to his lodge. If he or any Fasters wished to continue the Sun Dance, the Sun-Lodge was permitted to stand for them. Otherwise, it was torn down. Only the sun-pole with the buffalo head on top was left to mark the spot of the traditional Sun Dance.

The Dancer and all of the Fasters recovered honorably from their sacred experience.

In due time, the Chief of the Hidatsa tribe declared that the Dancer had won his daughter in marriage.

The Dancer went to the high ground, and in gratitude prayed and praised the Sun-God for the many blessings bestowed upon him and his beloved wife, and upon his tribe.