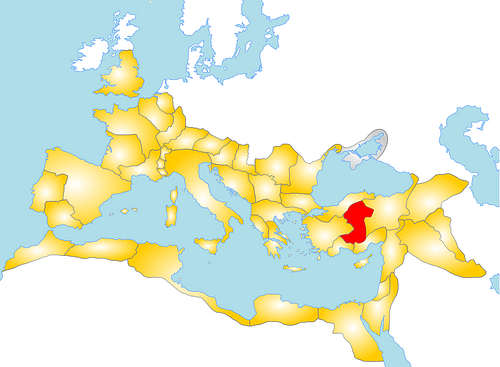

Galatia was a region in north-central Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) settled by the Celtic Gauls c. 278-277 BCE. The name comes from the Greek for "Gaul" which was repeated by Latin writers as Galli. The Celts were offered the region by the king of neighboring Bithynia, Nicomedes I (r. 278-255 BCE) and established themselves in three provinces made up of four cantons (wards) comprised of city-states (known as oppidum) governed, respectively, by the three tribes which made up the initial group: the Tectosages, Trocmil, and Tolistogogii.

The Galatian Celts retained their culture at first, continuing to observe their ancient religious festivals and rituals, but gradually became Hellenized to the point that they were referred to as Greek-Gauls by some Latin writers. They were conquered by Rome in 189 BCE, becoming a client state, but were granted a degree of autonomy under the reign of Deiotarus ("the Divine Bull", r. c. 105 to c. 42 BCE) after Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-44 BCE) defeated Mithridates VI (r. 120-63 BCE) of Pontus in 63 BCE and was later absorbed into the Roman Empire in 25 BCE by Augustus Caesar. It is best known from the biblical book of Galatians, a letter written to the Christian community there by Paul the Apostle.

Celtic Invasion & Establishment

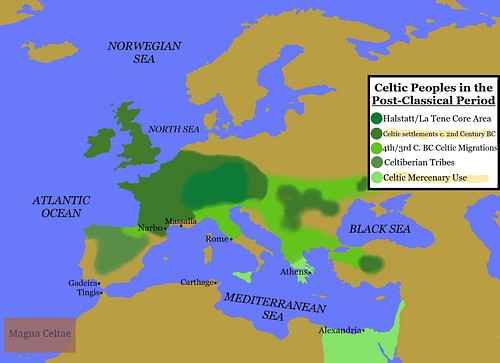

Celtic migration was already underway by the time of the sack of Rome by the Gauls, 390 BCE, under the leadership of Brennus. It continued down through the 4th century BCE when, around 280 BCE, a group of Celts from Pannonia descended on the region of Greece, offering their services as mercenaries (as they had in Italy almost one hundred years earlier) and living off the land through forage and pillaging towns and cities.

In 279 BCE, one part of this large migratory force (under another Brennus, leading scholars to speculate that "Brennus" may have been a title, not a proper name) sacked the sacred site of the Oracle at Delphi, carrying off its treasures. Brennus then disappears from history but two other leaders, Lutorius and Leonorius, were more interested in finding a permanent home for their people than continuous warfare and pillage and began looking to find land for this purpose.

At around this same time, King Nicomedes I of Bithynia (r. 278-255 BCE) in Anatolia was fighting with his brother, Zipoetes II, who had established an independent kingdom in Bithynia to challenge Nicomedes I's legitimacy. Nicomedes, hearing of the Celts' battle prowess, invited them into Anatolia to help him in his war. The Celts defeated Zipoetes II, established Nicomedes I as rightful king, and then began marauding through Anatolia extorting protection money from cities and villages and destroying those who would not pay.

Nicomedes I, having benefited from their help enormously, had no more need of them but was in no position to ask them to leave. Scholar Gerhard Herm comments on the situation:

Nicomedes had hired the barbarians; they had given him the freedom of maneuver he needed to secure his own state, but he then faced the question as to what should now be done with them. To anticipate demands for pay or whatever he cleverly worked on the great longing that had impelled the three tribes to their wanderings; he offered them territory in that part of Anatolia east of his frontiers, the region around modern Ankara. This gambit offered a dual advantage: on the one hand, he would be rid of these guests; on the other, he would create a buffer-state between himself and the wild Phrygians. Besides, the land was not even his. (40)

The land actually belonged to or was at least in use by the Phrygians, but Nicomedes seems to have felt this was the Celts' problem to resolve; which they did by simply settling there and driving Phrygian communities out. Having grown used to warfare and simply taking what they wanted from the local populace, however, they continued their sporadic raids. Around 275 BCE, possibly encouraged by Nicomedes, they raided the territories of the Seleucid Empire and were defeated by the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter (r. 281-261 BCE) at the Battle of the Elephants. They sued for peace and became valuable mercenaries in Antiochus I's army.

Attalus I & Galatia

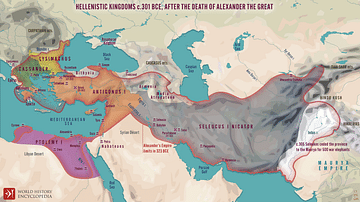

Whatever form the communities and government took in Galatia at this point is unclear but it was not a centralized state nor were the Celts content with a sedentary life of agriculture. While one tribe continued fighting for Antiochus I, another became mercenaries for Mithridates I Ctistes of Pontus (r. 281-266 BCE) against the Seleucids. At the same time, the third tribe, or possibly a combined force of two or all three, continued raiding other settlements and became a serious concern of the city of Pergamon. Pergamon had been under the control of Lysimachus, one contender in the Wars of the Diadochi ("successors"), who held Anatolia and Thrace after Alexander the Great's death. He was killed in battle in 281 BCE by Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE), another of the Diadochi and founder of the Seleucid Empire, who then claimed Anatolia.

Lysimachus had earlier entrusted Pergamon, the site of his large treasury, to one of his commanders, Philetaerus (r. 282-263 BCE) who protected Lysimachus' assets. Shortly after Lysimachus' death, Seleucus I was assassinated and his successor, Antiochus I Soter, knew nothing about the treasure (which, according to the ancient historian Strabo, amounted to over 9,000 talents of silver). Instead of offering the money to his new overlord, Philetaerus spent it discreetly in improving not only his city but those of his neighbors, quietly expanding his territory as he bought the loyalty of surrounding communities through lavish gifts.

By the time of his death, Pergamon was an opulent city with an acropolis dedicated to the goddess Demeter and temples to the patron goddess Athena. He had fortified the city against the Celts but this did not stop them from harassing trade caravans or assaulting the city. This problem continued into the reign of his successor, his nephew Eumenes I (r. 263-241 BCE) who resolved the issue by hiring the Celts as mercenaries.

Eumenes defeated Antiochus I Soter at the Battle of Sardis in 261 BCE with the help of the Celts, who killed Antiochus I, and freed Pergamon from Seleucid control. Eumenes then expanded his territories and engaged in grand building projects but the Celts of Galatia, formerly employed by Antiochus I and now jobless since Eumenes was not interested in further military campaigns, turned their attention to raiding his territory. The only way Eumenes could keep them at bay was to pay them protection money.

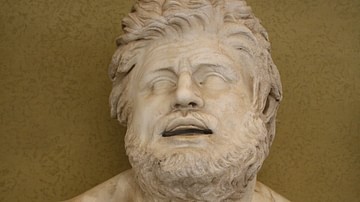

Eumenes was succeeded by his cousin and adoptive son Attalus I (r. 241-197 BCE) who refused to continue these payments and attacked the Celts, driving them back to Galatia by 232 BCE. In 230 BCE, he repulsed a large contingent of Celts marching on Pergamon to reestablish the protection money and again drove them back to their region. Attalus I then celebrated his victory through monuments and statuary depicting dying and defeated Gauls which he had situated in Pergamon's Temple of Athena. The famous statue The Dying Gaul (presently housed in the Capitoline Museum, Rome) is a later Roman copy of one of these statues commissioned by Attalus I. While his celebrations and monuments were being raised, Attalus I officially recognized the Gauls' region as Gallo-Graecia, granting them autonomy and encouraging them to establish their own kingdom.

Government & Religion

The three tribes, fiercely independent and refusing to unite with each other, established separate provinces in Galatia which amounted to small kingdoms. The Trocmil took the east, the Tolistobogii the west, and the Tectosages the central region. Each of these province-kingdoms was divided into four cantons, each one governed by a tetrarch with a judge beneath him, a military leader under the judge, and two subordinate commanders under him. The people were expected to live according to the laws formulated by the tetrarch (essentially their king) in conference with the judge whose powers were considerable in establishing and enforcing the law.

In order to prevent abuse of the judge's power, he was held responsible to a senate of 300 delegates made up of all three kingdom-provinces which would decide important cases (especially capital crimes such as murder), and who met regularly at a sacred site known at the Drunemeton. Gerhard Herm comments:

A nemeton was, in Celtic France and Britain as well, the peaceful, sacred place roughly corresponding to the temenos or original form of the Greek temple: here priests ruled and sacrifice was made to the gods. The prefix dru-…[came from] drus, the Greek name for an oak. In Celtic Ireland, the word for an oak was daur, and it must be obvious even to a layman that this word resembles the Greek equivalent as distant cousins sometimes do. The Drunemeton was thus a place of worship overlooked by oaks, both a sacred grove and a shaded stopping-place: hence the Galatian parliament must itself have been sacred in character. (42)

Legal practices seem to have been derived from a combination of Celtic and Phrygian traditions but this is unclear. The assembly of the Drunemeton is said by some scholars to resemble the Celtic tuath (meaning "people" but also "territory" or those dependent on a territory or chieftain) in that the tuath also convened in assemblies and the law applied was ultimately derived from the gods. That Galatian law was derived from the gods is suggested by the proximity of the sacred city of Pessinus, dedicated to the Mother Goddess Cybele and her consort Attis, close on the border of the western part of Galatia controlled by the Tolistobogii. Strabo claims that Pessinus was the religious center of the Galatians even though they did not control the city.

Pessinus was an ancient site which grew up around a great black stone which was said to have fallen from the heavens and symbolized the goddess whom the Galatians worshipped under her Phrygian name, Agdistis. Among Agdistis' many responsibilities were protection, law, and order. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Galatians regularly visited Pessinus and may have even taken the city at some point in order to elevate their standing in the region by controlling the central religious site.

The Battle of Magnesia & Rome

The Galatians gradually assimilated with the surrounding people, adopting Syrian-Greek and Phrygian customs and dress, and continued in their by-now traditional role as mercenaries for various kingdoms and principalities. They fought for the Seleucid king Antiochus III (the Great, r. 223-187 BCE) on his campaigns to reunify his empire between c. 210-204 BCE and formed a significant part of his forces when he invaded Greece in 191 BCE to fight the Romans.

Antiochus III was defeated at Thermopylae by the Romans in 191 BCE and again at the pivotal Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE where his forces were badly beaten and routed. Antiochus III was left with no choice but to accept all of Rome's terms as stipulated in the Treaty of Apamea in 188 BCE, which, among other conditions, severely reduced his empire and laid a heavy war indemnity on the Seleucids. The Galatians now found themselves again unemployed but this was the least of their problems.

The Romans at Magnesia had been allied with Eumenes II of Pergamon (r. 197-159 BCE, son of Attalus I), who had been forced to repeatedly drive Galatian war parties – no doubt encouraged by Antiochus III – away from his city. At Magnesia, the Romans saw the Galatian warriors in combat, serving as infantry and light cavalry, first-hand and the Roman consul Gnaeus Manlius Vulso (c. 189 BCE) recognized they could be worthwhile military assets.

Since Rome was still allied with Eumenes II, and found him useful, Vulso could not open negotiations with his enemies but could punish the Galatians for supplying forces to Antiochus III. In 189 BCE, Vulso marched on Galatia, instigating the Galatian War in which he defeated the Celts at the Battle of Mount Olympus and again at Ankara within the year. He had acted on his own impulse, without consulting the Roman senate, and so was at first charged with obstruction of the peace since negotiations were underway with the Seleucids for their surrender and Vulso had just attacked Seleucid allies. After explaining his rationale, however, he was cleared of all charges and rewarded with a triumph in Rome. Galatia was now a client state of the Roman Republic with the tetrarchy essentially a puppet government of Rome and Galatian mercenaries serving in the Roman army.

Strabo (l. 63 BCE to 23 CE) notes that, by his time, the tetrarchy of Galatia had gradually become a monarchy and the greatest of its kings was Deiotarus, a friend of Pompey the Great and the orator Cicero (l. 106-43 BCE), host to Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) when he visited Galatia, and later the associate of Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE). Deiotarus participated in the Mithridatic Wars as an ally of Pompey, sided with Pompey against Caesar in their war, was pardoned by Caesar afterwards, and restored to power by Mark Antony after Caesar's assassination when others wanted him deposed.

Deiotarus shared rule of the kingdom with his son-in-law Brogitarus (r. c. 63 to c.50 BCE) whose son, Amyntas (c. 38-25 BCE) would be the last king of Galatia. After Mark Antony's defeat by Octavian at the Battle of Actium (31 BCE), Octavian became the supreme power in Rome and, by 27 BCE, had become Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE), the first emperor of the Roman Empire. When Amyntas was assassinated in 25 BCE, Augustus made Galatia a Roman province.

Saint Paul & Christianity

Early on, the Galatians seem to have adopted the worship of the Phrygian sky god Sabazios, the all-powerful horseman of the heavens brought to Anatolia by the Phrygians and depicted as in periodic conflict with the indigenous Mother Goddess Cybele. Cybele (originally Kybeleia, meaning "mountain") was the goddess of the ancient Luwians and Hatti of the region from as early as c. 2500 BCE and, although venerated by the Phrygians, may have been gradually displaced by Sabazios if the interpretation of the Roman relief of the horse of Sabazios placing its hoof on the lunar bull of Cybele (presently in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts) is correct in assuming this means primacy of the god over the goddess.

Sabiazos is depicted as a warrior on horseback wielding a staff or spear and trampling the world-serpent who symbolized chaos. The Phrygians invoked him as a powerful war god and relied on him far more than they did Cybele. The Galatians may have gone in this same direction but, even if they did not, by the time of the missionary work of St. Paul (l. c. 5 to c .64 CE) in Anatolia, they were receptive to the message of a single all-powerful male deity who offered salvation through belief in his son. As Sabiazos was associated with Zeus, and Zeus' famous son Heracles (the Roman Hercules) was already an established savior-figure in Anatolia, the conversion of the pagan paradigm to the Christian would not have been difficult.

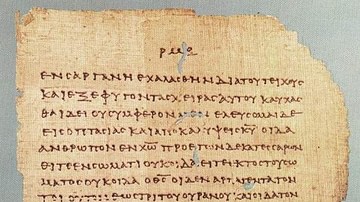

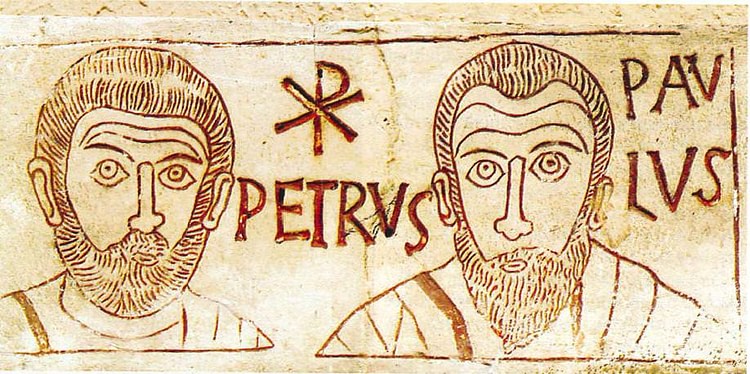

Paul most likely encouraged this conversion in the same way as he is seen doing in the Book of Acts and the epistles of the Christian New Testament, arguing that his new faith was simply the actual truth represented inadequately by the old gods. He is famously said to have used this argument in Acts 17:16-34 when he speaks to the Greeks of Athens in the Areopagus, stressing how their "unknown god" is the Jesus Christ he is representing. Paul himself says that he presents himself and his message to audiences in terms they will understand in I Corinthians 9:22 when he writes, "I became all things to all men so that by all means I might save some" and there is no reason to doubt he employed this same philosophy and argument in Galatia to win the people to Christ.

In his letter to the Galatians, he appeals directly to their well-known love of freedom and independence (5:1) and repeatedly contrasts freedom of the spirit through Christ with the slavery offered by pursuing worldly pleasures. He even specifically cites behavior and sins long associated with the Galatians such as jealousy, drunkenness, liberal sexuality, and idolatry (5:19-20) and contrasts these with the freedom from vice and corruption offered by Christianity (5:22-24). His appeals worked well and the Galatians were converted, exchanging Sabiazos' and Cybele's protection for that of Jesus Christ. Herm notes that "the Christian communities under the jurisdiction of the Drunemeton were among the oldest founded" by Paul and Galatia grew into one of the most vital Christian centers of the region (43).

The Galatians by this time were almost thoroughly Hellenized and had further substituted their Celtic-Greco customs with Roman beliefs and attitudes. Christianity replaced their old religion and the temples were turned into churches. This same paradigm was repeated, with the addition of military force, following the Muslim Invasion of Anatolia in 830 CE when the populace was converted to Islam and churches became mosques. By this time, there was little left of the original Celtic-Greco culture of Galatia. Its name survives today primarily through the biblical epistle of St. Paul and, possibly, the suburb of Galata outside of Istanbul, Turkey.