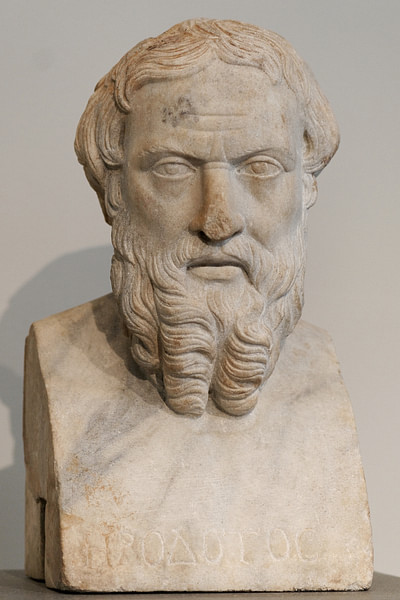

Herodotus (l. c. 484 – 425/413 BCE) was a Greek historian famous for his work Histories. He was called The Father of History by the Roman writer Cicero, who admired him, but has also been rejected as The Father of Lies by critics, ancient and modern, who claim his work is little more than tall tales.

While it is true that Herodotus sometimes relays inaccurate information or exaggerates for effect, his accounts have consistently been found to be more or less reliable. Some early criticism of his work has been refuted by later archaeological evidence which proves that his most-often criticized claims were, in fact, accurate, were based on accepted information of the time, or are the result of mistranslation or misinterpretation on his part.

While it is clear that he makes a number of claims now recognized as wrong, there is still much in his work that he has gotten right. His Histories often points the way to understanding a given event or cultural paradigm even when the details he provides are wrong or exaggerated. In the present day, Herodotus continues to be recognized as 'The Father of History' and a reliable source of information on the ancient world by the majority of historians.

Reliability

Criticism of Herodotus' work seems to have originated among Athenians who took exception to his account of the Battle of Marathon (490 BCE) and, specifically, which families were due the most honor for the victory over the Persians. More serious criticism of his work has to do with the credibility of the accounts of his travels.

One example of this is his claim of fox-sized ants in Persia who spread gold dust when digging their mounds. Herodotus writes:

Now, in the sand of this desert there are ants which are bigger than foxes, although they never reach the size of dogs; there are also some of these ants in the Persian king's palace, which were caught in the desert and taken there. Anyway, these ants make their nests underground, and in so doing they bring sand up to the surface in exactly the same way that ants in Greece do (they are also very similar to Greek ants in shape), and the sand which is brought up to the surface has gold in it. (III.102)

This account was regularly rejected until, in 1984, the French author and explorer Michel Peissel, confirmed that a fox-sized marmot in the Himalayas did indeed spread gold dust when digging and that accounts showed the animal had done so in antiquity as the villagers had a long history of gathering this dust.

Peissel also explains that the Persian word for mountain ant was very close to their word for marmot and so it was established that Herodotus was not making up his giant ants but, since he did not speak Persian and had to rely on translators, was the victim of a misunderstanding in translation.

This same scenario could apply to other observations and claims found in Herodotus' histories though, certainly, not all. In the interests of telling a good story, Herodotus sometimes indulged in speculation and, at other times, repeated stories he had heard as though they were his own experiences.

This is especially notable in his description of Babylon which, it seems, he never visited. He never claims to have done so but his description is so vivid and his use of phrases such as "still standing in my day" (I.181 in referring to the ziggurat of Babylon) have encouraged the understanding that his is an eye-witness account. Modern-day scholarship has proven Herodotus wrong on a number of points regarding Babylon, notably his claim regarding sacred prostitution (I.199) and the absence of medical professionals in the city (I.197). Even so, there is much in his Babylonian narrative that is accurate and this same applies to the rest of his work. Scholar Robin Waterfield sums up the best answer regarding Herodotus' reliability:

Herodotus himself does not expect us to believe everything we read. For him, the word historie continued to carry its Ionian meaning of `research' or `investigation, enquiry' and he often emphasizes that what he gives us is provisional information, the best that he has been able in his researches to discover. He sometimes interrupts the ongoing account in his first-person voice as the narrator, precisely to remind us not to treat the ongoing narrative as definitively true. (xxvii-xxviii)

As is the case with many ancient historians, truth in Herodotus does not always equate with historical fact but there is always some element of historical truth to a passage even if the details are inaccurate. In the often-criticized passage of I.199 on sacred prostitution, for example, that policy may not have actually been practiced but his narrative reflects the patriarchy's overall view of women as utilitarian objects, even in a culture where women had more rights than in others.

Early Life & Travels

While little is known of the details of his life, it seems certain that he came from a wealthy, aristocratic family in Asia Minor who could afford to pay for his education. His skill in writing is thought to be evidence of a thorough course in the best schools of his day. He wrote in Ionian Greek and was clearly well read. His ability to travel, seemingly at will, also argues for a man of some means. It is thought he served in the army as a hoplite in that his descriptions of battle are quite precise and always told from the point of view of a foot soldier.

Waterfield comments on Herodotus' early life:

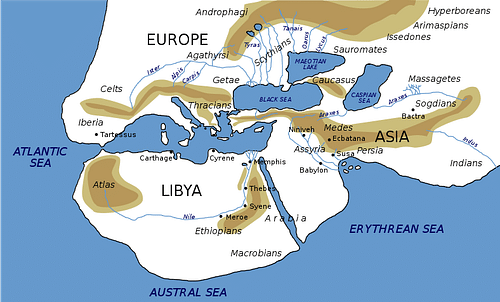

Herodotus was not a native of Athens. He was born in Halicarnassus (the modern Turkish city of Bodrum), about the time of the Persian Wars. Halicarnassus was a Dorian town with substantial intermarriage among its Greek, Carian, and Persian populations...If the later ancient reports that have come down to us are correct, his family was exiled during the troubled years after the Persian Wars, and as a very young man Herodotus may have lived on the island of Samos. His occasional comments in the Histories show us that he travelled widely around the world of the east Mediterranean. We do not know when and how the Histories were first written down; very likely, however, they arose out of recitations or readings that he gave over a number of years in other Greek cities and in Athens at the height of its imperial power. (x)

If Waterfield is correct, Herodotus' early experience with travel would have shaped his later inclinations; he does not seem to have stayed in any one place very long. He moves fluidly through his work from culture to culture and is always most interested in telling a good story and less so with fact-checking the details of the tales he heard and repeats in his pages. It is this tendency of his, as noted, which has given rise to the centuries of criticism against him.

The Histories

While it is undeniable that Herodotus makes some mistakes in his work, his Histories are generally reliable and scholarly studies in all disciplines concerning his work (from archaeology to ethnology and more) have continued to substantiate all of his most important observations.

Herodotus identifies himself in the prologue to his work as a native of Halicarnassus (on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, modern Turkey) and this is accepted as his birthplace even though Aristotle and the Suda claim he was a native of Thurii (a Greek colony in the region of modern-day Italy). This discrepancy is generally understood as a mistake made in an ancient source (possibly a translation of Herodotus' work) as Herodotus may have lived at Thurii but had not been born there.

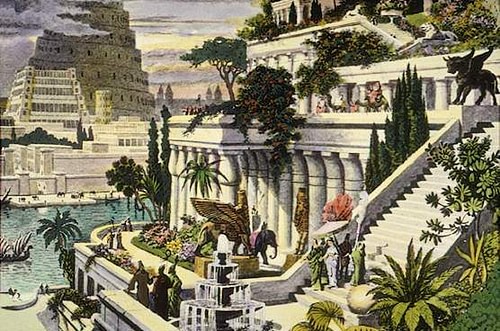

He traveled widely in Egypt, Africa, and Asia Minor and wrote down his experiences and observations, providing later generations with detailed accounts of important historical events (such as the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE and the engagements of Thermopylae and Salamis in 480 BCE) everyday life in Greece, in Egypt, in Asia Minor, and on various "wonders" he observed in his travels. His description of the city of Babylon as among these wonders is an example of why his work has often been criticized. Herodotus writes:

Babylon lies in a great plain, and in size it is such that each face measures 22½ km, the shape of the whole being square; thus the circumference is 90 km. Such is the size of the city of Babylon, and it has magnificence greater than all other cities of which we have knowledge. First there runs round it a deep and broad trench, full of water; then a wall fifty meters in thickness and hundred meters in height [...]. At the top of the wall along the edges they built chambers of one story facing one another; and between the rows of chambers they left space to drive a four-horse chariot. In the circuit of the wall there are set a hundred gates made of bronze. (Histories, I.178-179)

Archaeological evidence, as well as other ancient descriptions, clearly indicates that Babylon was not as large as Herodotus describes and had nowhere near 100 gates (it had only eight). It has thus been determined (as noted above) that this account was based on hearsay, rather than a personal visit, even though Herodotus seems to give the impression that he visited the site himself. As he had a great appreciation for the works of Homer (he bases the arrangement of his Histories on Homer's form) his passage on Babylon is thought to be emulating the earlier writer's description of Egyptian Thebes. Scholars W.F.M. Henkelman, et. al., comment:

The inevitable question faced by researchers again and again with respect to this description is the ‘reliability’ and hence ‘usefulness’ of the information transmitted. But the approach to this important question has not always been free of assumptions; more often than not, it has proceeded on the basis of certain tacitly assumed premises. Thus, for example, it was widely accepted that Herodotus personally visited Babylon. Similarly, it was axiomatic that Herodotus received his information from local informants, since he was regarded as a ‘proto-historian’ operating in accordance with the rules established for modern research and thus would only transmit information that he had himself received. (450)

As Henkelman and his co-authors note (as Waterfield and others have observed) much of the criticism of Herodotus stems from applying modern standards of historical research to ancient narratives. For Herodotus, as for many writers of antiquity, factual detail was not as important as a good story. His penchant for storytelling, and his obvious talent for it, have alarmed and annoyed his critics since antiquity but this very quality in the Histories is also what has made the work so greatly admired. Herodotus is able to bring a reader into the events of the stories he relates by creating vivid scenes with interesting characters and, often, offering explanations for events that draw more closely on mythology than history.

He was hardly an impartial observer of the world he wrote about and often gives personal opinions at length on various people, customs, and events. While his admiration for Homer is always evident, he freely questioned the historical truth of the Iliad, asking why the Achaeans would wage so lengthy and costly a campaign as the Trojan War on behalf of one woman. This is only one of many examples of Herodotus' personality displaying itself in his work. Waterfield comments:

Certain kinds of narrative recur strikingly enough [in the Histories] to make us feel we are seeing the idiosyncratic taste of the narrator emerging - that he enjoys a particular kind of story and, given the option, includes it when possible. Herodotus is fascinated by the interplay of nature and culture; the Scythians, living in a treeless land, invent a way of cooking meat in which the animal's bones and fat provide the fire and the stomach provides the pot in which the meat is cooked (4.61). He also singles out clever individuals and great achievements; he enjoys noting the `first inventor' of something, or a particularly striking building, or boat, or custom, or other cultural achievement. (xxxviii)

Herodotus' personality, in fact, comes through quite often in the pages of his works. A reader understands that one is hearing from an individual with certain tastes and interests and that the author considers that what he has to say is important enough to require no explanation, qualification, or apology for perceived inaccuracy; if Herodotus felt like including something, he would include it and he never seems to care if readers found fault with that.

Herodotus in the Histories

That he held himself in quite high regard is apparent in the prologue to the Histories which begins,

These are the researches of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, which he publishes, in the hope of thereby preserving from decay the remembrance of what men have done, and of preventing the great and wonderful actions of the Greeks and the Barbarians from losing their due meed of glory; and withal to put on record what were their grounds of feuds. (I.1)

Unlike other ancient writers (such as Homer, earlier, or Virgil, later), Herodotus does not attribute his narrative to divine sources, nor call on such for assistance, but announces clearly that this is his work and no one else's. His high opinion of himself is also displayed in what is recorded as the first publication of the Histories at the Olympic Games.

Works at this time were published by being read aloud and the Greek writer Lucian of Samosata (l. 125-180 CE) claims that Herodotus read the entirety of his work to the audience in one sitting and received great applause. Another version of the publication of the work, however, claims that Herodotus refused to read his book to the crowd until there was ample cloud cover to shade him on the platform. While he waited, the audience left, and this event is what gave rise to the maxim, “Like Herodotus and his shade” alluding to one who misses an opportunity by waiting for optimal circumstances.

Whichever account is true, if either is, they both reflect the high opinion Herodotus seems to have had of himself but also the high regard in which he was held. In both stories, an audience attends the reading of his work and either praise him or wait in the sun as long as they can endure it just to hear him read.

Later Life & Death

After travelling the world of his time, Herodotus did come to live in the Greek colony of Thurii where he edited and revised the Histories later in life. He had also lived in Athens and, at some point, it is thought he returned there. Scholars consider it likely that he died in Athens of the same plague that killed Athenian statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE) sometime between 425 and 413 BCE.

His fame was so great that many different cities (Athens and Thurii among them) claimed to be the site of his funeral and monuments were erected in his honor. The lasting significance of his work continues to be appreciated by millions of people today and, as noted, he continues to be regarded as a primary source for reliable information on the ancient world he observed and wrote about. Even his passages which have been challenged or rejected still offer a reader significant insight into the event or culture he describes, even if only to illustrate how a Greek writer viewed the culture and practices of non-Greeks.