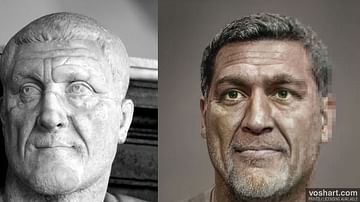

Valerian ruled as emperor of the Roman Empire from 253 CE until his capture in 260 CE. In 253 CE an elderly Roman military commander and experienced former senator was proclaimed emperor by his troops - a very common occurrence at the time. As emperor Publius Lucinius Valerianus - commonly referred to as Valerian - would battle repeated incursions from the north and east, rarely stepping foot in Rome. Eventually, however, he would meet his unfortunate death at the hands of an enemy king and so become the only emperor to ever die in captivity.

An Unstable Empire

The last half-century had been a difficult one for Rome, for the Empire had been ruled by a series of less-than capable emperors, and for decades to come it would see more of the same. In a 50 year period from 235 to 285 CE there were at least 20 emperors with the majority dying in battle or by assassination. Most historians point to the year 180 CE as marking the demise of the Pax Romana or Roman Peace. For the next two centuries, until it finally surrendered to “barbaric” invasions, the Empire in the west struggled socially, politically, and economically.

Early Life

Coming from an old Roman family, the future emperor Valerian was born in 195 CE (place unknown) during the reign of Septimius Severus (193 to 211 CE), and, like many before him, he rose through the ranks before sitting on the throne of Rome. He served as consul under Severus Alexander (222- 235 CE) and in 238 CE supported the rebellion of the two elder Gordians against Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus and his father Maxminus Thrax (235 – 238 CE). However, his path to power would not be an easy one. From 249 CE to 253 CE the Empire saw four men ascend to the imperial throne. Valerian would finally don the robe in 253 CE and wear it until his unfortunate death in 260 CE.

Immediate Predecessors

The first of the four emperors was a descendant of an old senatorial family. Gaius Messius Quintus Decius (249 – 251 CE) - also known as Trajanus Decius - was a former senator, and governor of Nearer Spain and Upper Moesia. Like many before him (and many after), Decius had been declared emperor by his devoted troops following the death of Marcus Julius Verus Philippus, known to historians as Philip the Arab (244 – 249 CE). Philip obtained the label “Arab” because he was the son of an Arab chieftain. In an attempt to restore order, Philip had sent Decius to be the new governor of both Moesia and Pannonia. After defeating the always invading Goths and restoring stability, Decius's men proclaimed him emperor, and with additional legions at his disposal and the encouragement of his troops, in September of 249 CE, Decius marched towards Rome. The armies of Philip and Decius met at Verona where Philip was defeated and killed. Philip was supposedly in poor health at the time and considered by many to be a weak commander. Shortly afterwards, his young son and heir was killed at the Praetorian camp in Rome.

Unfortunately for Decius, battling alongside Trebonianus Gallus against the Goths, he and his son Herennius would meet the same fate as his predecessor - killed in battle. This time, however, it was by a foreign enemy not their own soldiers. His death, however, may not have been as simple as it seemed. Some claim the emperor's demise may have been due to a betrayal by his lieutenant and soon-to-be successor Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus (251 – 253 BCE).

Aside from an excellent career in the military, the new emperor Gallus had been both a former senator and governor of Upper Moesia. Although some believed he should have immediately avenged the death of Decius, one of Gallus's first actions as emperor was to not only continue the persecution of the Christians (Philip had been more tolerant) but also make an unfavorable peace treaty with the Goths - Rome would pay tribute while the Goths kept the plunder as well as the prisoners of war. Gallus believed the more-than-favorable terms would keep the Goths from any further invasions into Roman territory but he was wrong. Another shallow gesture was to adopt Decius's younger son Gaius Valens Hostilianus Messius Quintus. Unfortunately, the young heir-apparent would die in the plague that ravaged the empire and army.

Gallus's short reign was, in the words of one historian, “a period of continuous disasters” with the outbreak of the plague as well as an unanswered threat from the Persian ruler Shapur I and his invasion of Armenia. For reasons unknown, until Valerian, Shapur had been largely ignored by Rome - even though he had had an aggressive policy towards Roman territories for over a decade - eventually devastating Cappadocia and Syria while capturing over thirty-three cities, including Antioch.

Rise to Power

While Gallus was content with establishing himself in Rome, north of the Danube, Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus, the one-time senator, consul, and governor of Lower Moesia, attended to the marauding Goths - the Gothic commander Kniva was demanding an increase in tribute. After being declared emperor by his men in the summer of 253 CE - Aemelian had promised his men sizeable bonuses if they were victorious over the Goths - he marched southward to Italy. The Roman Senate immediately declared him a public enemy. Decius and his son Gaius Vibius Volusianus sent word to Valerian to gather troops at Raetia and assist them against the approaching Aemilian. Unfortunately, Valerian was delayed and would not arrive in time, for Decius and his son were killed at Interamna by their own troops who immediately, not surprisingly, swore allegiance to Aemilian. Upon his arrival in Rome, the same Roman Senate that had declared him an outlaw acknowledged him as emperor. However, the new emperor would not enjoy the luxury of wearing the imperial robe for very long.

Although he could not help Gallus, Valerian chose to continue his march towards Rome. During this long march, as with those before him, before leaving Raetia, he was declared emperor by his army. Immediately, Aemilian moved northward to meet him, and as history is often said to repeat itself, died at the hands of his own men in October of 253 CE near the town of Spoleto at the aptly named Pons Sanguinarius or Bridge of Blood. His men then swore allegiance to Valerian. A serious civil war had been avoided.

Valerian As Emperor

Arriving in Rome, Valerian hoped to bring order to the empire; however, external pressures aggravated internal economic, political, and moral demands. One historian said he inherited an empire “out of control.” Wisely, Valerian appointed his son Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus as co-emperor. After his father's death, Gallienus would serve alone until 268 CE but he would be murdered by his own staff officers. After sending his son northward to engage the always threatening Goths there, Valerian's first concern was to the repair the damage in the east caused not only by Shapur I, a situation long ignored by his predecessors, but also to deter the continued Gothic attacks; the Goths had decided to shift their efforts eastward eventually sacking the ancient city of Athens. Unfortunately, although the emperor would never return to Rome, his supposed minimal success in the east would surprisingly be rewarded with the impressive titles of Restorer of the Orient, Restorer of the Human Race, and Restorer of the World.

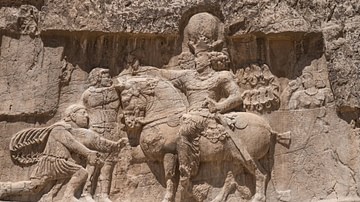

As he marched into Asia Minor, Valerian sent a contingent of troops to Byzantium to drive back the Burgundians and Goths who had attacked Thrace and Thessalonica and pushed further south across the Hellespont into Chalcedon and Bithynia, burning Nicomedia and Nicaea. Valerian finally arrived in Mesopotamia to aid Bithynia where his army, upon arrival, was ravaged by the plague. After a devastating defeat at the Battle of Edessa, the emperor chose to negotiate a peace treaty with the Persian king. In 260 CE, together with his general staff, including the Praetorian commander, Valerian met with Shapur to discuss terms, but the meeting turned into a trap.

Captivity & Death

According to some accounts, Valerian would spend the remainder of his life in Persia as a prisoner and slave - dragged in chains and forced to crouch down so Shapur could step on the emperor's back to mount his horse. Upon his death, Valerian's skin was removed and dyed, then shown to future temple visitors (mostly as a warning). Shapur's Res Gestae Divi Saporus or 'The Acts of the Divine Shapur' celebrated the emperor's capture. Valerian's death would never be avenged for Shapur would die from illness in 270 CE.

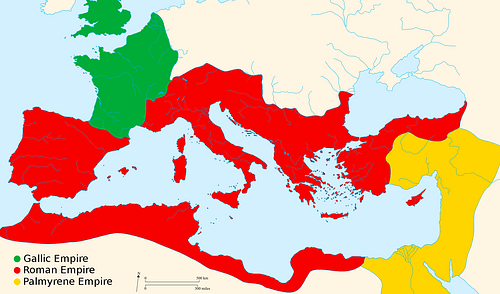

Many historians see Valerian as another example of a long series of incompetent emperors. Regrettably, the emperor, the only one to ever be captured and taken prisoner, would not be remembered solely for his capture and humiliation. In 257 CE he issued the first empire-wide edict ordering the persecution of the Christian Church. He seized Christian property and executed those Christians who did not recant their beliefs. Many Christian writers even claim his capture and treatment at the hands of Shapur was evidence of God's wrath. However, one innovative idea initiated by Valerian was later used by the emperor Diocletian. Before he moved eastward, Valerian divided the empire into two - he took the east while his son got the west. Sadly, Valerian would not be able to see this idea come to fruition. Had he been successful against Shapur, history may have viewed him differently.