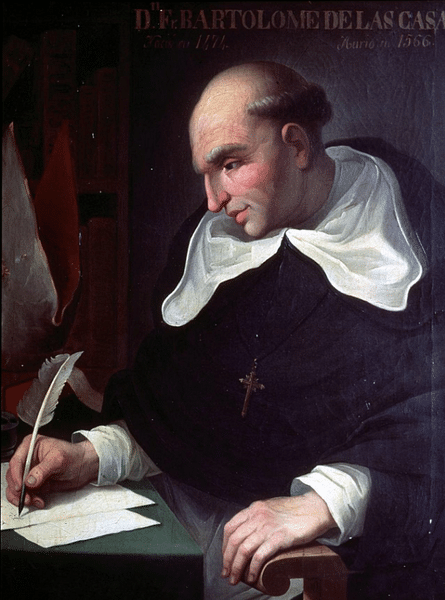

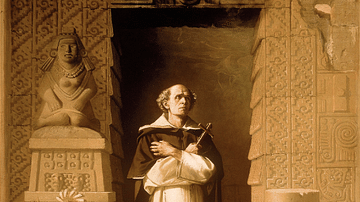

Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484-1566) was a Spanish Dominican friar and former conquistador who revealed the atrocities of the conquests of New Spain and Peru and who strove to protect the basic rights of indigenous peoples in the Spanish Empire. For this reason, Las Casas is often called the 'Defender of the Indians'.

Las Casas wrote his A Very Brief Recital of the Destruction of the Indies in 1522, a graphic, if perhaps exaggerated indictment of the rapacious and un-Christian behaviour of the conquistadors and first settlers in New Spain. Las Casas then put his ideas of tolerant governance into practice in Guatemala, where he achieved some success in establishing relations with the Kekchi Indians.

Early Life

Bartolomé de Las Casas was born in Seville, Spain, on 11 November 1484. He was educated at the cathedral academy of his native city and then sought fortune and adventure by sailing to the New World in 1502, where he settled on Hispaniola (today's Dominican Republic and Haiti). He then moved on and participated in the conquest of Cuba in 1511. What Las Casas witnessed in the colonies changed his life, especially the application of the encomienda system, where Spanish adventurers and settlers were granted the legal right to extract forced labour from indigenous tribal chiefs in the Americas colonies. In return, the Europeans were expected to give military protection to the labourers and offer them the opportunity to be converted to Christianity via the evangelism of a local priest. Las Casas had himself held an encomienda on Hispaniola and on Cuba, where he also had African slaves working his land, but the degree of maltreatment of indigenous peoples by Europeans in the colonization process, which was often little different from slavery, eventually convinced Las Casas to return to Spain where he renounced his worldly goods. He joined the Dominican religious order in 1515. In 1516, he took up the cause of the indigenous peoples in the Americas and was appointed by the Crown as 'Protector of the Indians'.

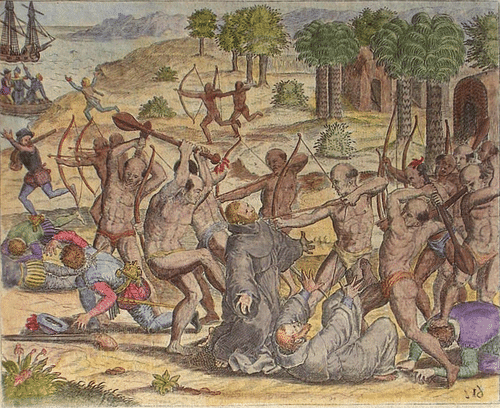

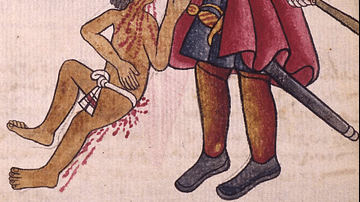

In 1522 the friar wrote his most famous work, a treatise describing the brutal reality of colonization. The horror story was dramatically titled A Very Brief Recital of the Destruction of the Indies and came with graphic engraved illustrations. The Brief Recital was a selected history (including exaggerations) that permitted Las Casas to forward his case that the conquistadors were guilty of genocide in their insatiable greed for wealth. As Las Casas put it, "if demons possessed gold they would undertake to steal it for themselves" (Alan Covey, 355). Above all, Las Casas exploded the myth that the conquistadors were noble Christians bringing light, civilization, and salvation to the peoples of the Americas. On the contrary, the Europeans, at least in the majority of cases, were bringing nothing less than an apocalyptic wave of death and destruction, which was rapidly depopulating the Americas. The author does not, however, specifically name the conquistadors guilty of the crimes of murder and torture he describes.

Influence on Colonial Policy

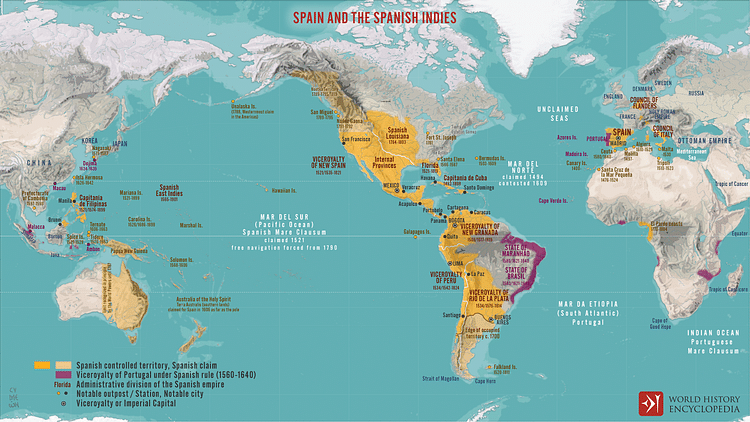

As noted, modern historians now regard some of Las Casas' descriptions of violence and sadism as being somewhat exaggerated, but the Brief Recital achieved its aim and brought to wider attention just what was going on in the New World. This was significant since the Spanish authorities had given themselves two objectives in forging a new empire: extract as much material wealth as possible from new territories and convert the locals to Christianity. The second objective was very much the concern of the Council of the Indies, the body made responsible for the governance of Spanish America and the Philippines in 1524. The Council was dominated by clergymen, and though they realised that exploitation of indigenous peoples was an inevitable part of colonization, they were keen that the indigenous people were given a minimum amount of protection that meant they could be educated and converted to Christianity. The Council's role prior to 1524 was largely carried out by a single individual, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca (b. 1451), a royal chaplain and archbishop of Burgos. Fonseca was temporarily replaced as a consequence of Las Casas' revelations, and perhaps the friar had even persuaded the Spanish Crown that a more formal institution was needed to manage the Spanish Indies, as the Americas were then known.

Las Casas' defence of American Indian rights did have a more concrete effect on colonial policy, as it was one of the factors that inspired the New Laws of 1542. This legislation attempted to abolish the encomienda system or at least seriously curb the worst episodes of mistreatment, but the combined avarice of the conquistadores and settlers – who rose up in violent rebellion – proved too great an obstacle, and the system remained in place for another 150 years. Even then, the encomienda system only petered out because of the dramatic population loss caused by the harshness of the system and deadly European diseases.

Fuelling the Black Legend

Another group intensely interested in Las Casas' reports were the enemies of Spain. Powers like England and France leapt upon the chance to bash the Spanish monarchy as a rapacious and brutal institution which presided over an even more blood-thirsty and intolerant people only out to murder and pillage in their colonies. The Protestant English, in particular, were delighted to find a new source to help build up their character assassination of the Spanish people in what became known as the 'Black Legend', a term coined by the Spanish historian Julian Juderias y Loyot (1877-1918). Las Casas' Brief Recital was soon translated into English, French, and Dutch, among other languages, and in Germany, it was graphically illustrated with prints by De Bry.

Other Works

Las Casas continued to write treatises calling for more humane treatment of indigenous peoples. His The Only Method of Attracting Men to the True Faith, written in 1530, promoted the idea that the best way forward for everyone was to treat local peoples not with force and brutality but with patience, persuasion, and affection. His essential beliefs were that all people should enjoy liberty since they possessed reason which naturally inclines humans to peaceful behaviour. Further, he believed that the popes had no right to depose non-Christian rulers and had no authority over non-Christian peoples. The popes had transferred some authority over Christians to European monarchs, but this did not then mean the subjects of those monarchs had any authority over the lives of those belonging to another state or culture. For Las Casas, the indigenous peoples of the Americas, once conquered by the Spanish monarchy or vassals acting in his/her name, had equal rights as any other Spanish citizen and should not be subject to violent acts or exploitation that infringed those rights. In return for the protection of their rights, the indigenous peoples had to swear allegiance to their new monarch. Las Casas believed that indigenous peoples should be left to rule themselves at a local level and even have an indigenous ruler who would promote Christianity much better than an imposed viceroy.

In 1565, in what seems an attitude centuries ahead of its time, Las Casas even presented Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598) with a petition calling for the return to the Inca people of all Inca treasures, tributes, and natural resources stolen since 1532. The petition was not successful, and it is to be remembered that the standard view of the period was that the pagan Inca Empire was being justly punished for its own rapacious policies towards conquered peoples. There were also plenty of church figures to take a stand against Las Casas, notably Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, a fellow Dominican. The two opposing views became known as the Valladolid debate after a public discussion in the monastery of San Gregoria in Valladolid in August 1550. De Sepúlveda argued that Americas peoples were natural slaves and so saw no problem at all with such arrangements as the encomienda, which was a necessary part of the 'civilizing' process. Las Casas argued that unlike Africans (who he did see as natural slaves and even encouraged their numbers to be increased in the Americas), the sophistication of the beliefs and culture of the Incas, in particular, meant they should be treated as potential converts and not mere beasts of burden.

Besides more philosophical works, Las Casas also wrote important histories of the region such as Historia and Apologetica historia, in which he attempted to piece together Inca history when very few Europeans were at all interested in such an endeavour.

The Great Experiment

Las Casas' writings were not at all typical, but, with a position on the royal council, he was influential enough to persuade the Crown to apply his theories to actual colonies, first on Hispaniola, where a community of indigenous peoples at Cumaná was left to govern itself under the peaceful guidance of missionaries. This first experiment was not a success, as European settlers fought the idea that their wide-ranging powers should be curbed in the interests of the Indians. Disappointed but undeterred by the fate of Cumaná, in 1521, Las Casas this time personally founded a colony on the coast of Venezuela. Here a community of European settlers and artisans lived under the guidance of a priest in a sort of common community. Las Casas' intention was to show the indigenous peoples by example how a more peaceful society might be constructed. This second experiment was another failure when the Indians attacked the colony and killed most of the inhabitants. Las Casas, bitterly disappointed, retreated to a Dominican monastery in the eastern part of Hispaniola, where he remained throughout the 1520s.

In 1533, Las Casas again came to wider attention when it was discovered that he was refusing absolution to holders of an encomienda. From 1534, Las Casas toured parts of Peru to see the empire-building situation in South America firsthand. Then, in 1537, the Spanish authorities, notably the king, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556), who was attracted by the humanitarian approach and idea that the conquistadors were far exceeding their authority, decided to let Las Casas try and put his ideas into reality for a third time. Events in South America as the Inca civilization succumbed to the conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541) were a sorry repetition of what had gone on in Mexico and Central America. The friar was given a portion of territory in what is today central Guatemala, but the catch was this land belonged to the extremely warlike and so far unconquerable Kekchi Indians. Las Casas was undeterred by the reputation of the Kekchi, and he learnt their language and toured the region with other Dominican friars. With the emphasis on peaceful persuasion, Las Casas achieved some success in forging relations with the Kekchi and spreading the Christian faith. Certainly, in the five years he spent there, Las Casas' approach was worthy of his name change of the region from "Land of War" to Verapáz or "Land of the True Peace". Unfortunately, the situation rapidly deteriorated following Las Casas' departure in 1542, and the consequent influx of Spanish settlers provoked a bloody Kekchi revolt.

Not quite finished with the Americas, Las Casas continued to be consulted as an expert witness by the Council of the Indies, and in 1544, he was appointed the bishop of Chiapas, the mountainous region in southern Mexico. As a legacy of the friar's humanitarian work there, the main cultural city in the state is today called San Cristóbal de las Casas. Bartolomé de Las Casas died in Madrid on 18 July 1566.